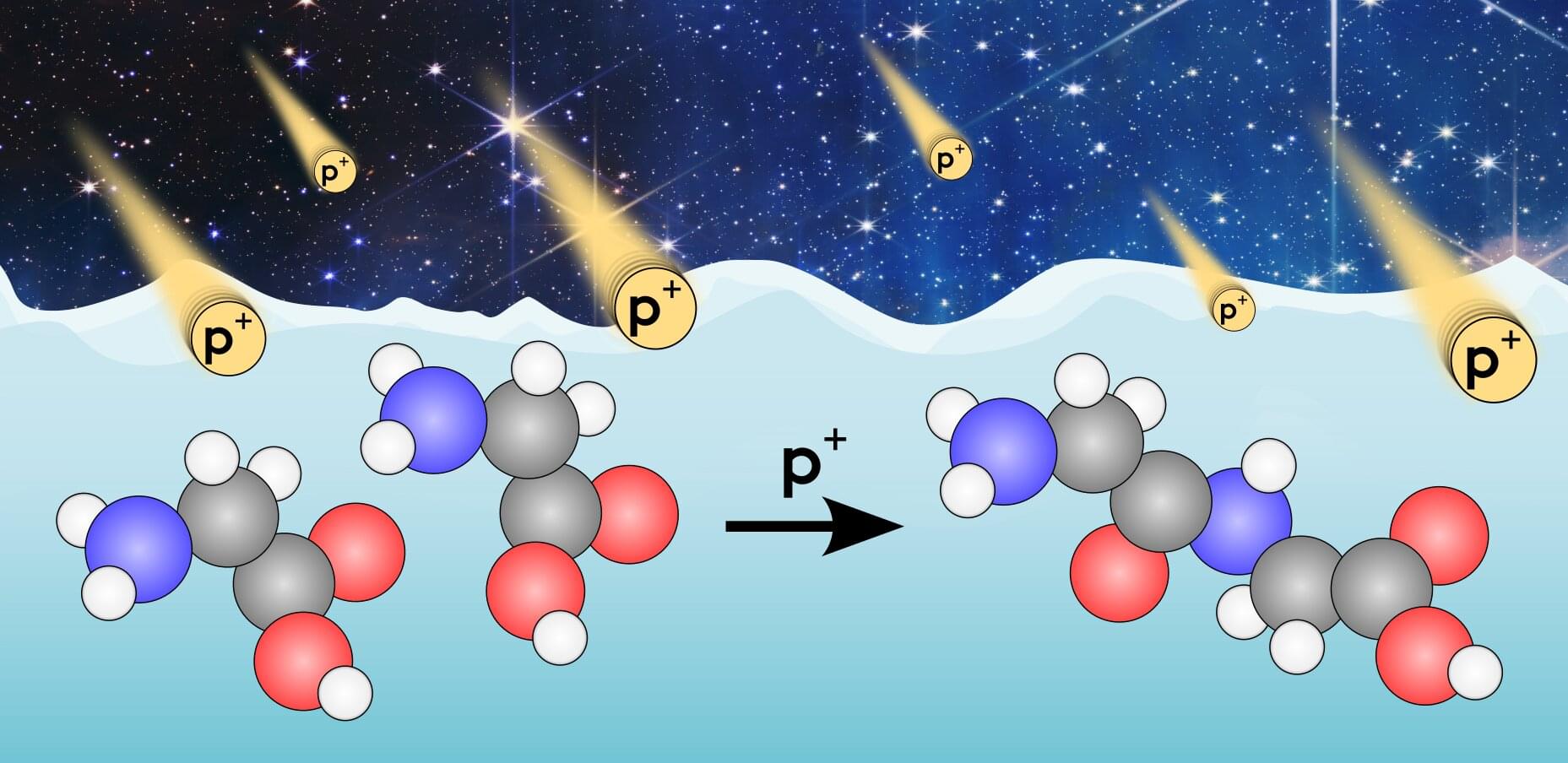

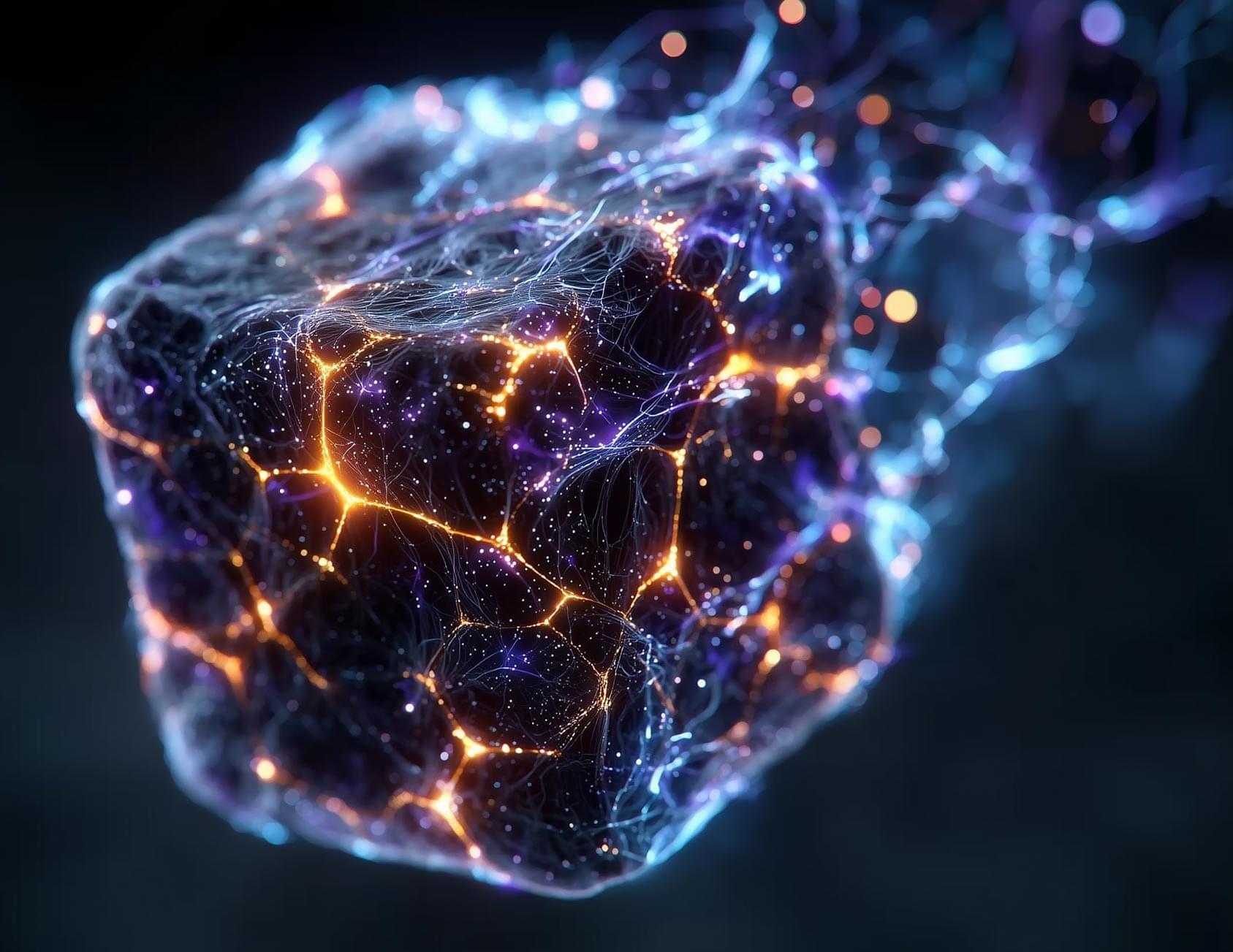

Can a small lump of metal be in a quantum state that extends over distant locations? A research team at the University of Vienna answers this question with a resounding yes. In the journal Nature, physicists from the University of Vienna and the University of Duisburg-Essen show that even massive nanoparticles consisting of thousands of sodium atoms follow the rules of quantum mechanics. The experiment is currently one of the best tests of quantum mechanics on a macroscopic scale.

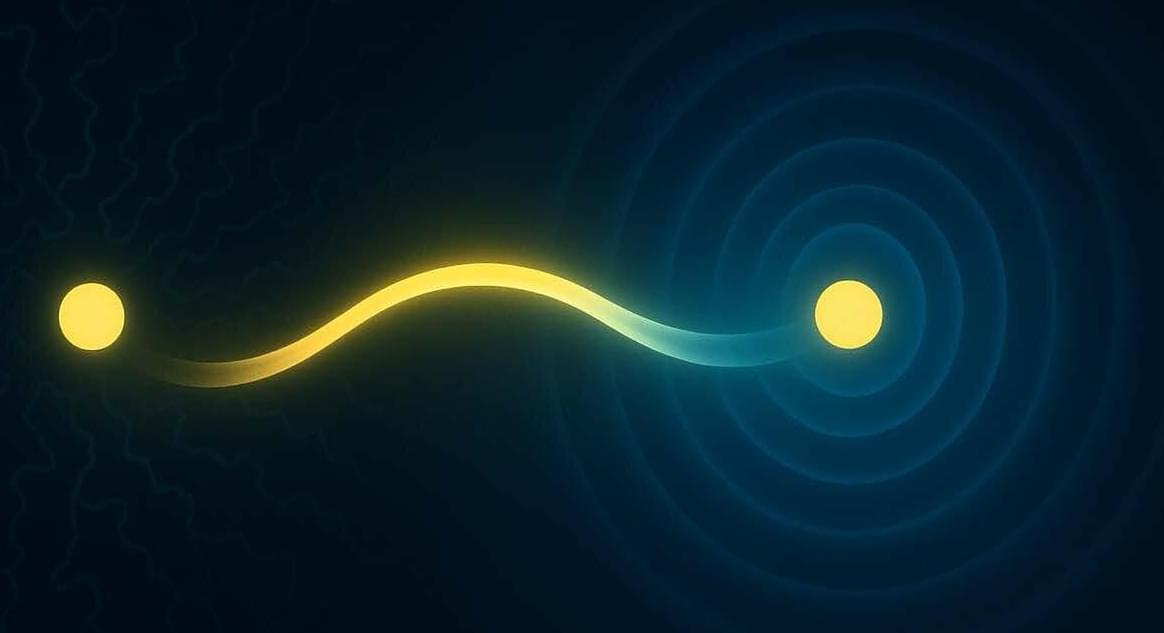

In quantum mechanics, not only light but also matter can behave both as a particle and as a wave. This has been proven many times for electrons, atoms, and small molecules through double-slit diffraction or interference experiments. However, we do not see this in everyday life: marbles, stones, and dust particles have a well-defined location and a predictable trajectory; they follow the rules of classical physics.

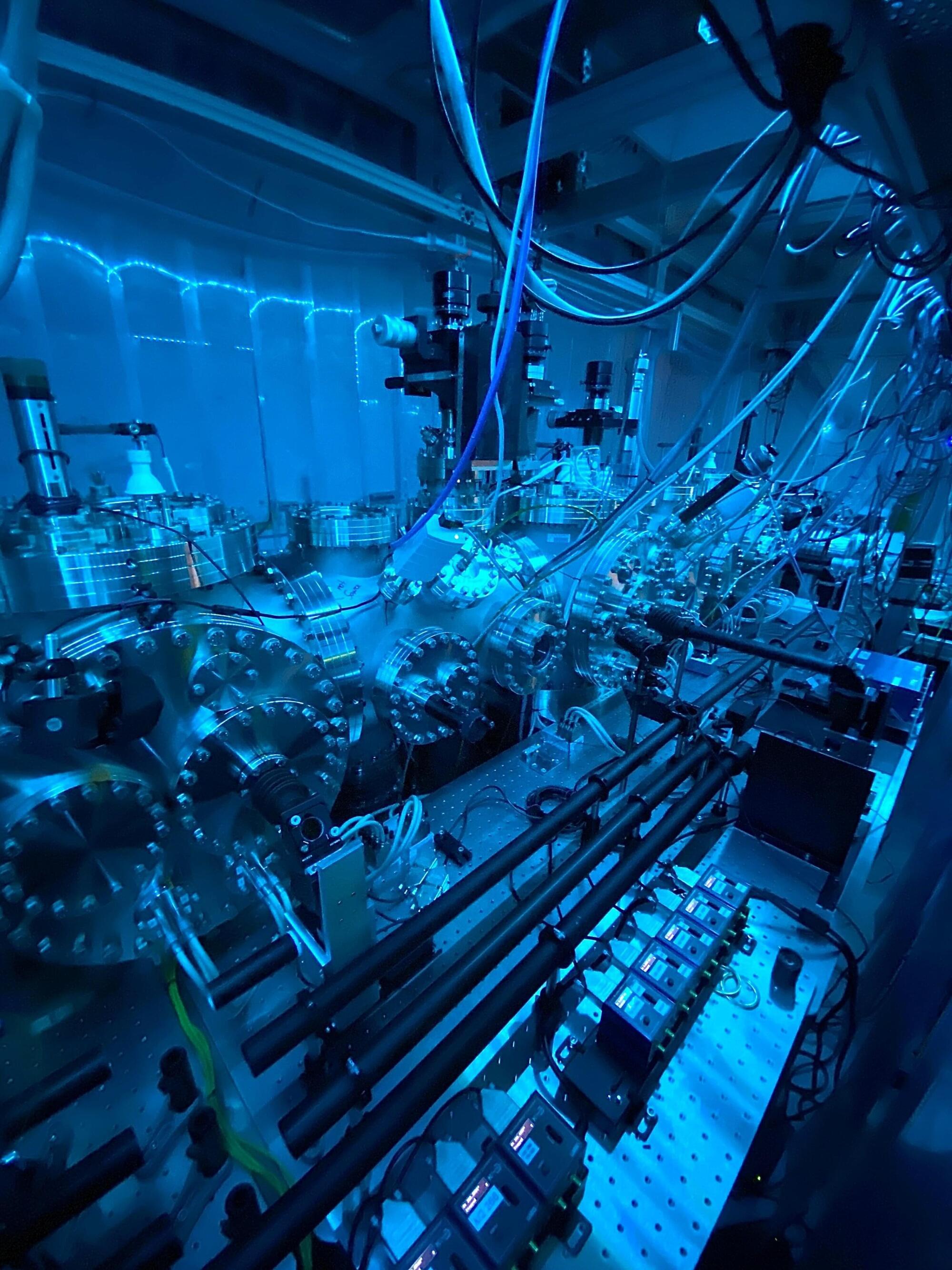

At the University of Vienna, the team led by Markus Arndt and Stefan Gerlich has now demonstrated for the first time that the wave nature of matter is also preserved in massive metallic nanoparticles. The scale of the particles is impressive: the clusters have a diameter of around 8 nanometers, which is comparable to the size of modern transistor structures.