US scientists decode diamond fusion fuel capsules’ flaws to maximize energy output.

A new study reveals how diamond capsules used in fusion energy experiments can develop flaws under extreme pressure.

US’ inverted D plasma research leads to breakthrough in nuclear fusion reactor control.

Scientists at the DIII-D National Fusion Facility are investigating a different approach to tokamak operation that has yielded promising results for the design of future fusion power plants.

Recent experiments have demonstrated that a plasma configuration known as “negative triangularity” can achieve the high-performance conditions necessary for sustained fusion energy, while also addressing a critical challenge related to heat management inside the reactor.

IN A NUTSHELL 🔬 The Los Alamos experiment achieved a fusion energy yield of 2.4 megajoules, marking a significant breakthrough. 💡 The innovative THOR window system was used to create a self-sustaining “burning plasma.” 🔧 Modifications to the standard hohlraum allowed for the escape of X-rays, aiding in the study of radiation flow and energy

Terence Tarnowsky, a physicist at Los Almos National Laboratory (LANL), will present his results at the fall meeting of the American Chemical Society (ACS). ACS Fall 2025 is being held Aug. 17–21; it features about 9,000 presentations on a range of science topics.

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Lea este comunicado de prensa en español

WASHINGTON, Aug. 18, 2025 — From electric cars to artificial intelligence (AI) data centers, the technologies people use every day require a growing need for electricity. In theory, nuclear fusion — a process that fuses atoms together, releasing heat to turn generators — could provide vast energy supplies with minimal emissions. But nuclear fusion is an expensive prospect because one of its main fuels is a rare version of hydrogen called tritium. Now, researchers are developing new systems to use nuclear waste to make tritium.

US nuclear graveyard scanned with advanced LiDAR tech for safety, risk mapping.

The 3D imaging tool helped them come up with a detailed picture of the conditions of the safe storage enclosures for six cocooned reactors and identify potential issues.

“These inspections are critical to ensuring the cocooned reactors continue to function as designed,” said Tashina Jasso, acting director with the HFO’s Site Stewardship Division.

“The inspections are part of our commitment to reducing risk and preserving infrastructure for long-term management and safe disposal.”

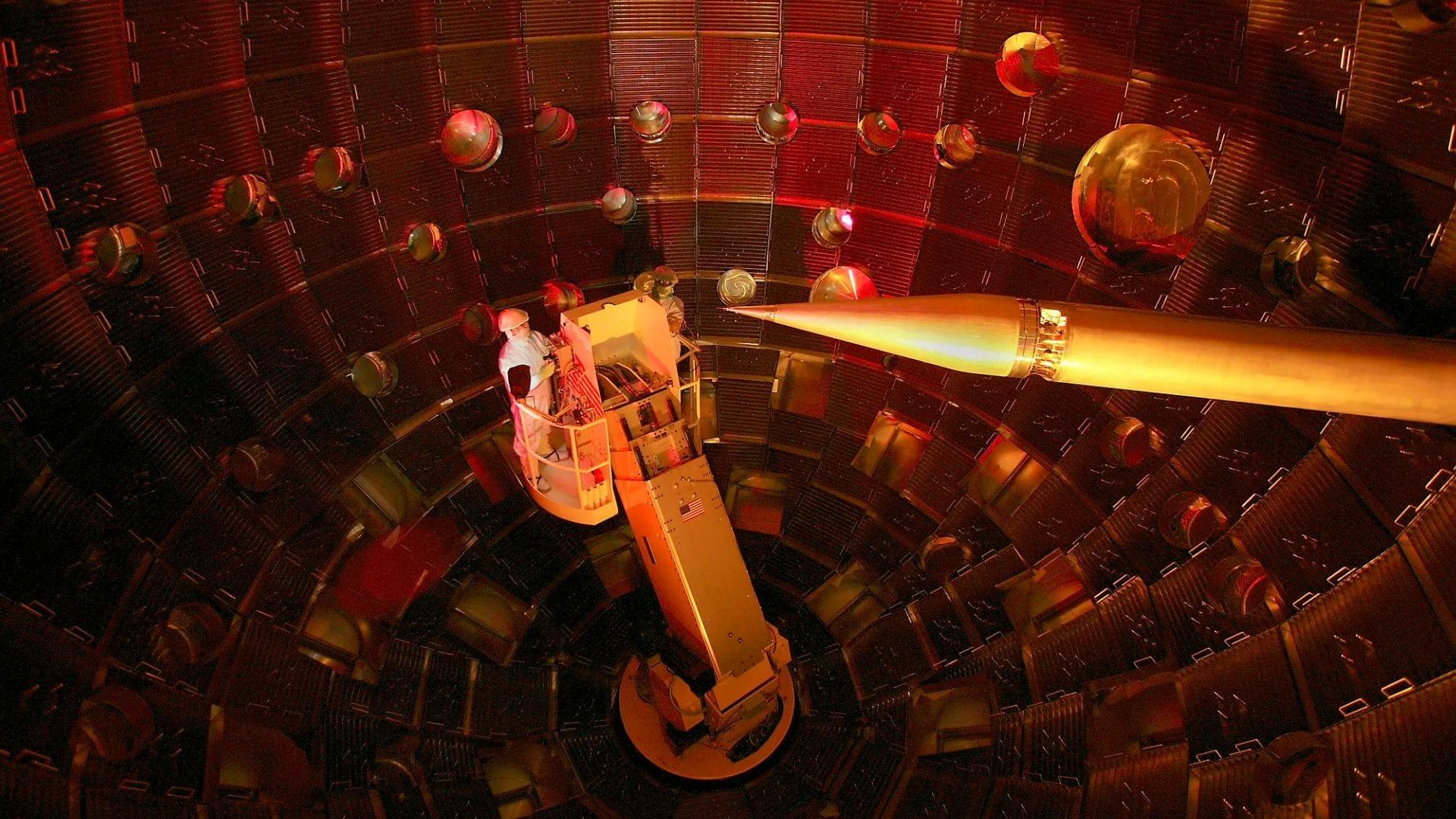

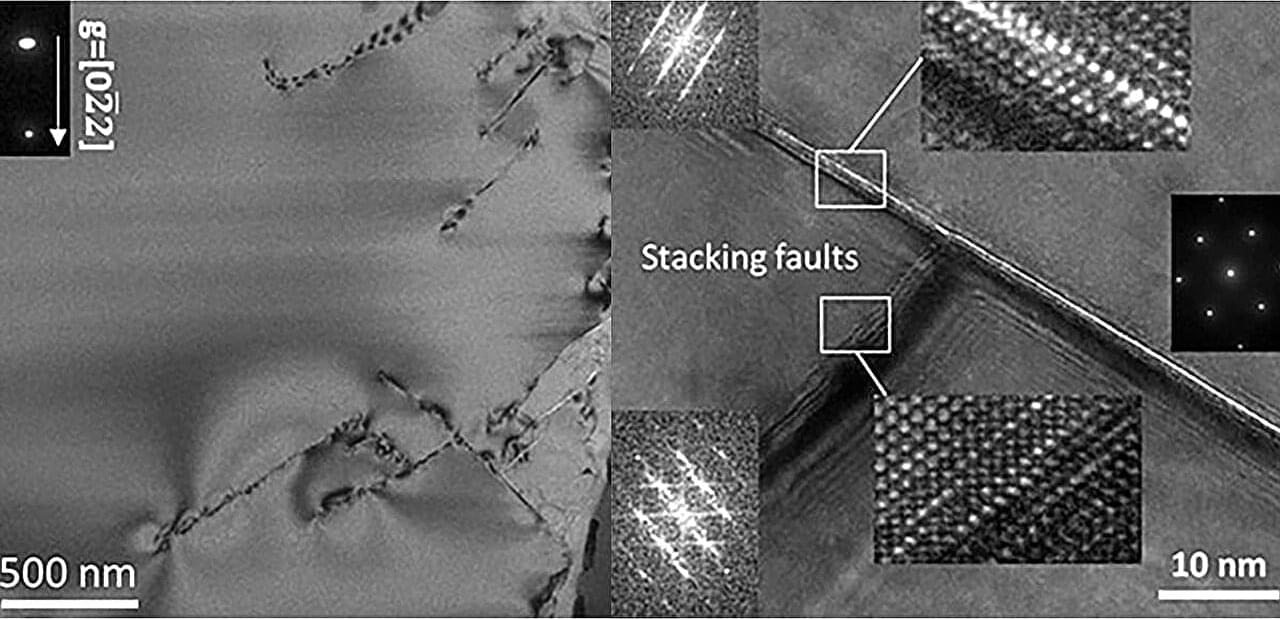

Scientists at the University of California San Diego have uncovered how diamond—the material used to encase fuel for fusion experiments at the National Ignition Facility (NIF) in Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory—can develop tiny structural flaws that may limit fusion performance.

At the NIF, powerful lasers compress diamond capsules filled with deuterium and tritium to the extreme pressures needed for nuclear fusion. This process must be perfectly symmetrical to achieve maximum energy output.

By using a high-power pulsed laser to simulate these extreme conditions, researchers found that diamonds can form a series of defects, ranging from subtle crystal distortions to narrow zones of complete disorder, or amorphization. These imperfections can disrupt the implosion symmetry, which in turn can reduce energy yield or even prevent ignition.

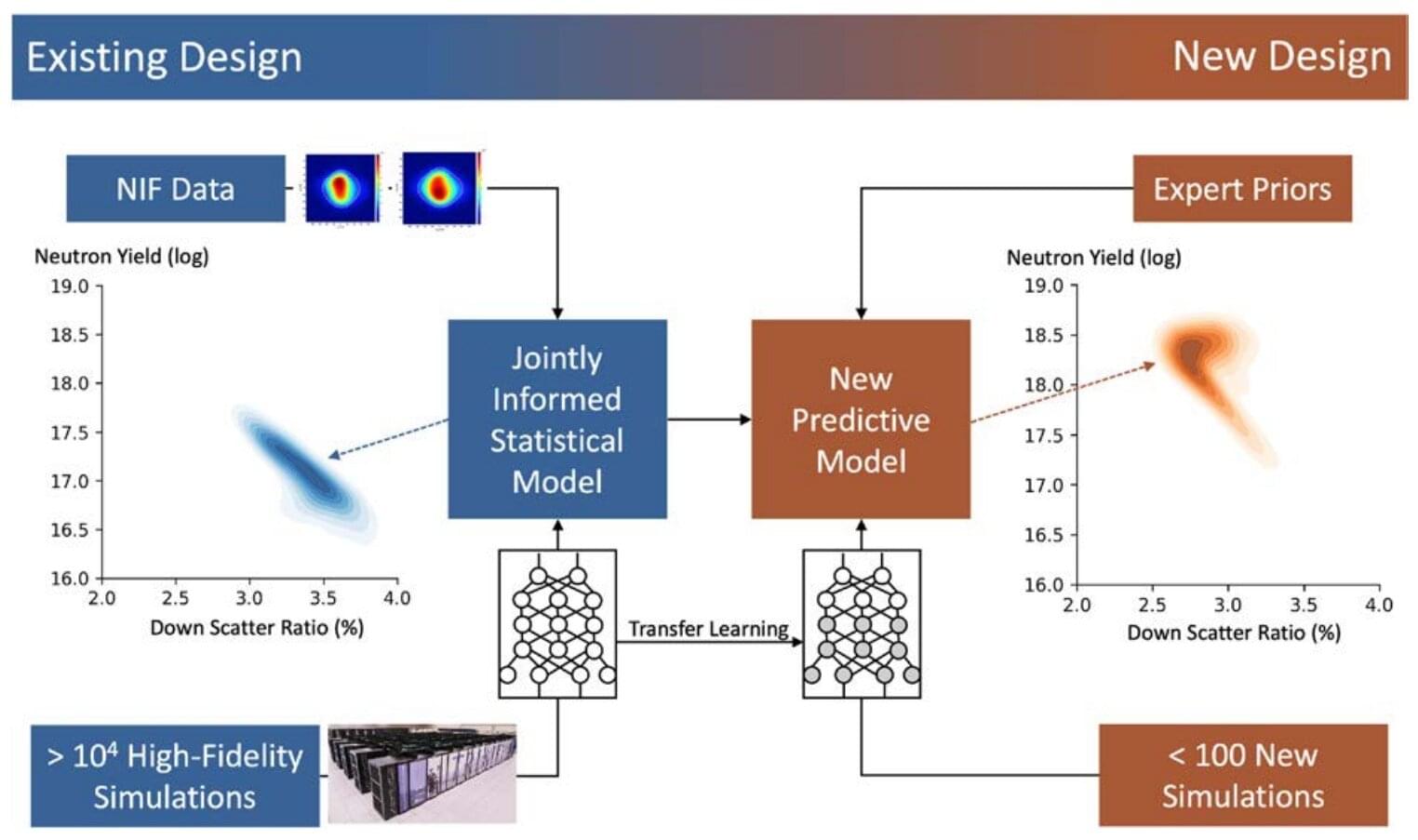

Practical fusion power that can provide cheap, clean energy could be a step closer thanks to artificial intelligence. Scientists at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory have developed a deep learning model that accurately predicted the results of a nuclear fusion experiment conducted in 2022. Accurate predictions can help speed up the design of new experiments and accelerate the quest for this virtually limitless energy source.

In a paper published in Science, researchers describe how their AI model predicted with a probability of 74% that ignition was the likely outcome of a small 2022 fusion experiment at the National Ignition Facility (NIF). This is a significant advance as the model was able to cover more parameters with greater precision than traditional supercomputers.

Currently, nuclear power comes from nuclear fission, which generates energy by splitting atoms. However, it can produce radioactive waste that remains dangerous for thousands of years. Fusion generates energy by fusing atoms, similar to what happens inside the sun. The process is safer and does not produce any long-term radioactive waste. While it is a promising energy source, it is still a long way from being a viable commercial technology.