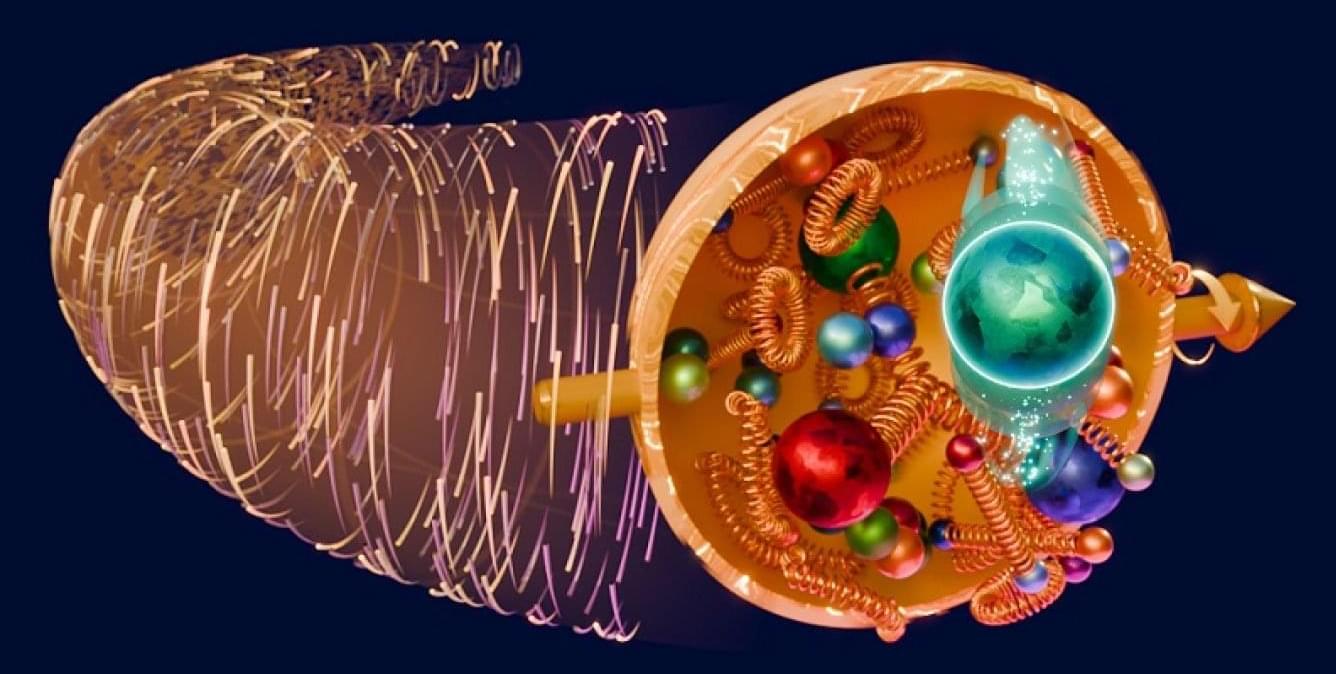

High‑energy physics has always been one of the main drivers of progress in superconducting science and technology. None of the flagship accelerators that have shaped modern particle physics could have succeeded without large‑scale superconducting systems. CERN continues to lead the efforts in this field. Its next accelerator, the High‑Luminosity LHC, relies on high-grade superconductors that were not available in industry before they were developed for high-energy physics. Tomorrow’s colliders will require a new generation of high‑temperature superconductors (HTS) to be able to realise their research potential with improved energy efficiency and long‑term sustainability.

Beyond the physics field, next‑generation superconductors have the potential to reshape key technological sectors. Their ability to transmit electricity without resistance, generate intense magnetic fields and operate efficiently at high temperatures makes them suitable for applications in fields as diverse as healthcare, mobility, computing, novel fusion reactors, zero‑emission transport and quantum technologies. This wide range of applications shows that advances driven by fundamental physics can generate broad societal impact far beyond the laboratory.

The Catalysing Impact – Superconductivity for Global Challenges event seeks to accelerate the transition from science to societal applications. By bringing together top-level researchers, industry leaders, policymakers and investors, the event provides a structured meeting point for technical expertise and strategic financing. Its purpose is not simply to present progress but to build bridges across sectors, disciplines and funding landscapes in order to move superconducting technologies from early demonstrations to impactful applications.