These images have been selected to showcase the art that neuroscience research can create.

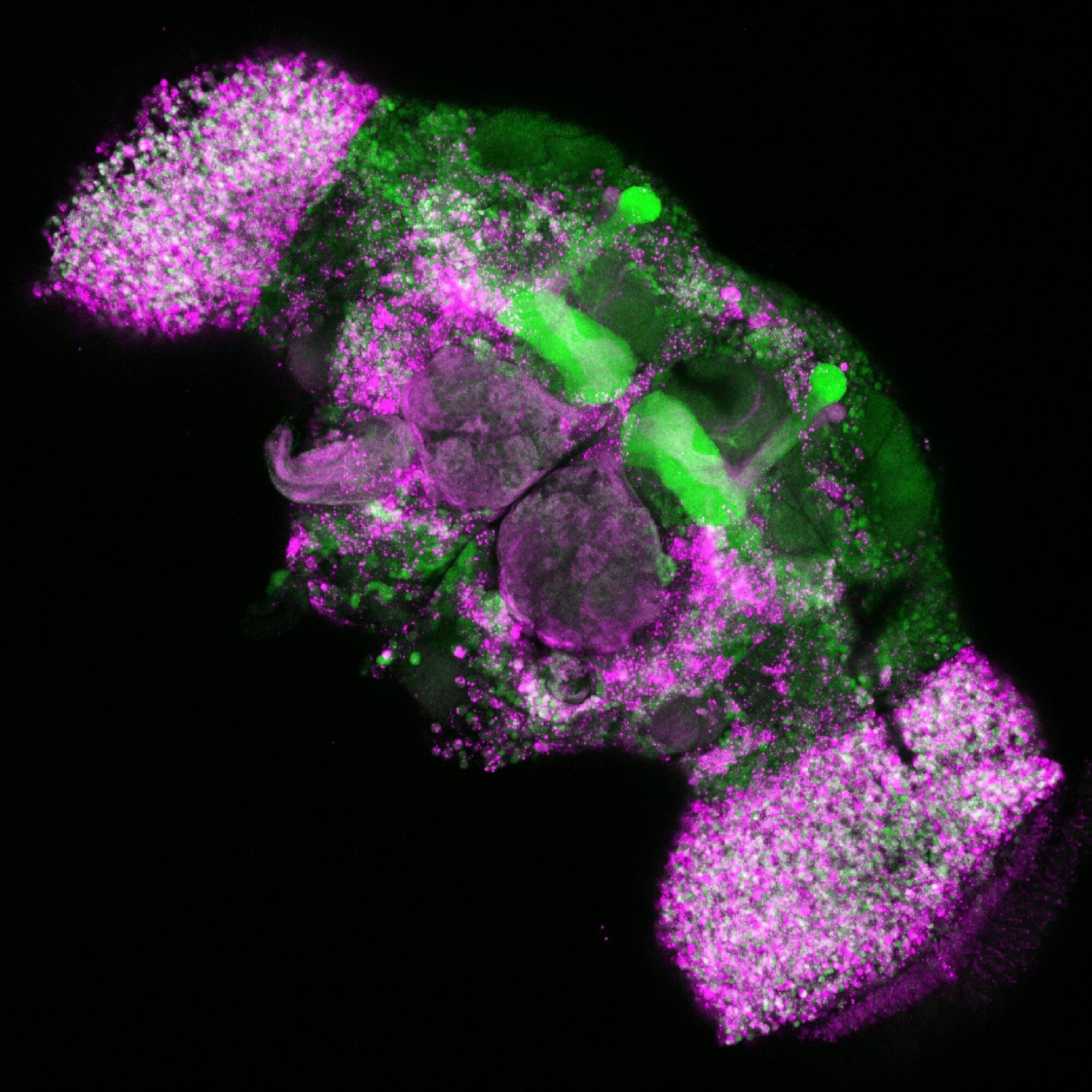

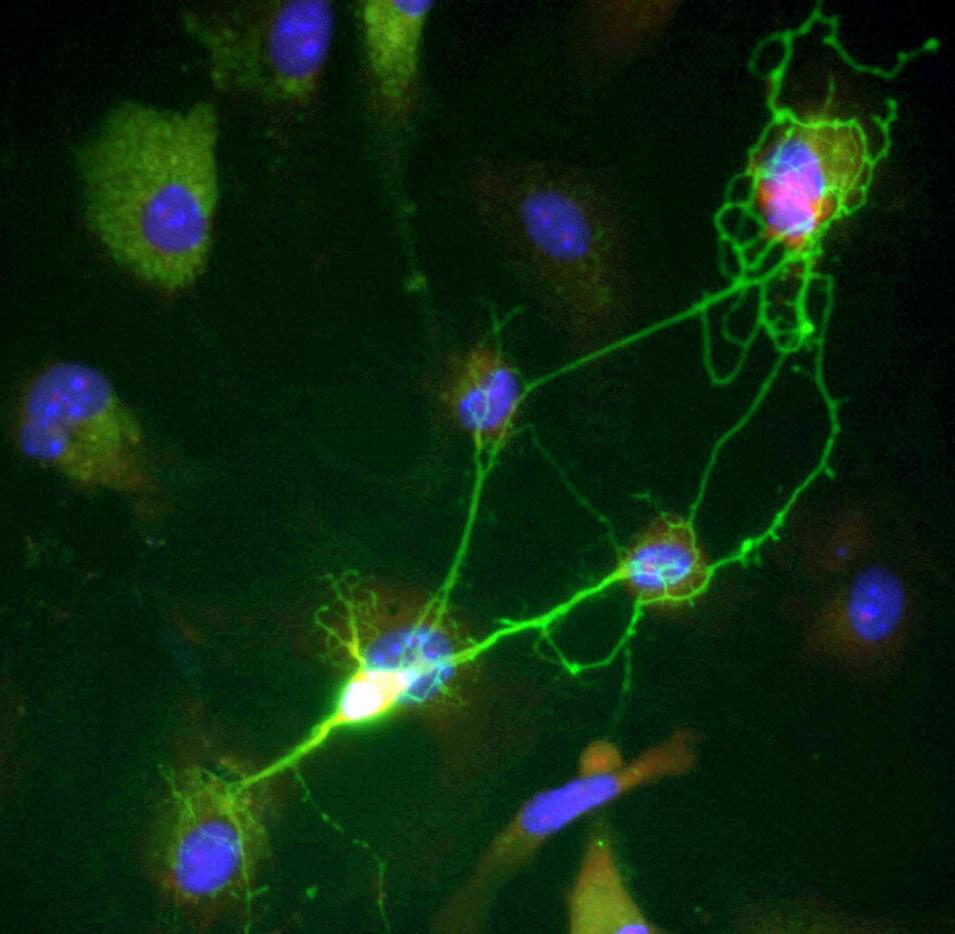

As described by the authors: The cacophony voltage-gated calcium channel serves as the primary conduit for the calcium that triggers neurotransmitter release at countless synapses across the fruit fly (Drosophila) nervous system. To support this role at different synapse types, alternate splicing confers different biophysical properties upon cacophony. However, conventional techniques that might discriminate splice isoforms, such as antibodies, toxins, and pharmacological agents, are poorly suited for identifying splice isoforms across multiple neurons in a living nervous system.

This image demonstrates the transgenic expression of a bichromatic fluorescent exon reporter in most neurons of the fly brain. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence was particularly bright relative to red fluorescent protein (TagRFP) in the α, β, and γ lobes of the mushroom body (MB), indicating a bias towards the inclusion of exon 11 at the expense of exon 10. Differences were also evident between neurons of the optic lobes.