People with obesity have an increased level of biomarkers related to Alzheimer’s disease in their blood, a new study has found.

Mental health is a global crisis, with more than 1 billion people affected by mental health conditions, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Young people are particularly affected, with suicide as the third leading cause of death among those aged 15 to 29. A new study of the mental health of Nepali adolescents published in the journal PLOS One found that more than 40% of teens suffer from anxiety and that parenting style is a major factor influencing mental well-being.

A research team led by Rabina Khadka, a public health lecturer at the Manmohan Memorial Institute of Health Sciences in Kathmandu, surveyed 583 school-going adolescents in Bheemdatt Municipality, Nepal. The aim was to fill in gaps in the existing data, specifically the lack of research on how different parenting styles (authoritative, authoritarian and permissive) relate to a range of mental health outcomes.

Participants were asked to fill out a four-part survey with questions covering their mental health status (levels of depression, anxiety, stress and self-esteem), perceived parenting style and personal information such as age, gender and family situation. The researchers then measured these factors using recognized psychological scales and analyzed the data to find statistical links between the type of parenting teens received and their mental health.

Semaglutide medications like Ozempic and Wegovy can help lower the risk of heart and metabolic diseases in people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, according to a study published in JAMA Psychiatry.

Glucagon-like peptide–1 receptor agonist (GLP-1RAs) drugs, such as semaglutide, mimic the natural gut hormone GLP-1 that regulates hunger and food intake. By activating GLP-1 receptors in the brain, the drug reduces hunger and slows gastric emptying, helping one feel full longer. It also enhances glucose-dependent insulin secretion, thereby improving blood sugar control.

Researchers in Denmark recruited 73 adults taking antipsychotic medications who were showing early signs of diabetes and had an average BMI of 36, which falls in the category of obesity. The participants, aged 18 to 65 years, were randomly assigned to receive either weekly semaglutide injections or a placebo for 6.5 months.

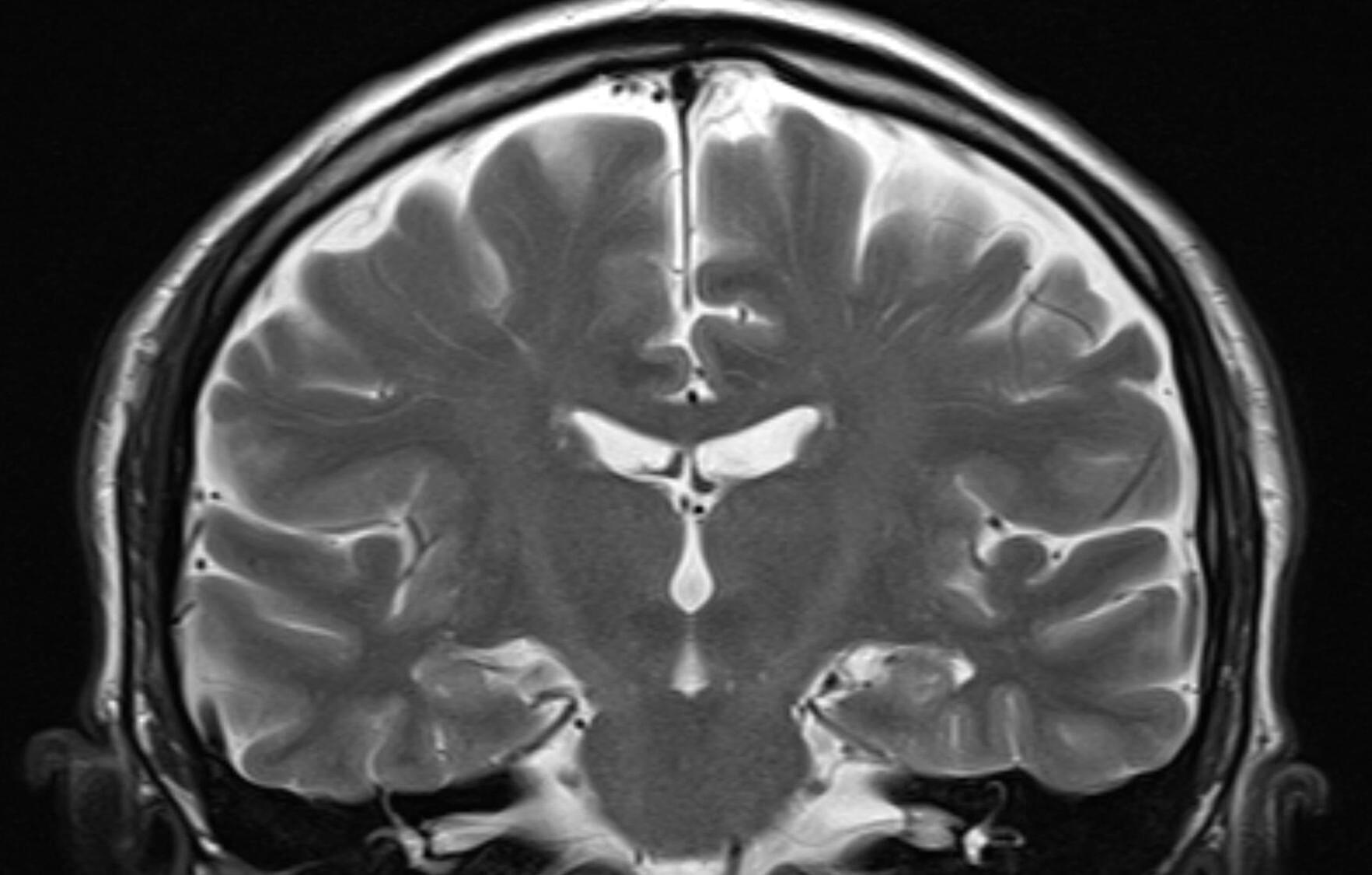

When it comes to brain function, neurons get a lot of the glory. But healthy brains depend on the cooperation of many kinds of cells. The most abundant of the brain’s non-neuronal cells are astrocytes, star-shaped cells with a lot of responsibilities. Astrocytes help shape neural circuits, participate in information processing, and provide nutrient and metabolic support to neurons. Individual cells can take on new roles throughout their lifetimes, and at any given time, the astrocytes in one part of the brain will look and behave differently than the astrocytes somewhere else.

After an extensive analysis by researchers at MIT, neuroscientists now have an atlas detailing astrocytes’ dynamic diversity. Its maps depict the regional specialization of astrocytes across the brains of both mice and marmosets—two powerful models for neuroscience research—and show how their populations shift as brains develop, mature, and age.

The open-access study, reported in the Nov. 20 issue of the journal Neuron, was led by Guoping Feng, the James W. (1963) and Patricia T. Poitras Professor of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT.

Integrated circuits are the brains behind modern electronic devices like computers or smart phones. Traditionally, these circuits—also known as chips—rely on electricity to process data. In recent years, scientists have turned their attention to photonic chips, which perform similar tasks using light instead of electricity to improve speed and energy efficiency.

An international collaboration led by Cornell researchers used a combination of psilocybin and the rabies virus to map how – and where – the psychedelic compound rewires the connections in the brain.

Specifically, they showed psilocybin weakens the cortico-cortical feedback loops that can lock people into negative thinking. Psilocybin also strengthens pathways to subcortical regions that turn sensory perceptions into action, essentially enhancing sensory-motor responses.

The findings published Dec. 5 in Cell. The lead author is postdoctoral researcher Quan Jiang.

Although scientists have made progress using brain-activity scans to convert the words we think into text, translating the rich, complex images in our minds into language is still far more difficult, says lead author Tomoyasu Horikawa.

Horikawa calls this approach “mind captioning” because the system turns distinct patterns of human brain activity into short text captions.

Earlier experiments often used the label “mind reading” and focused on easier tasks, such as guessing which object someone was viewing from a short list or matching brain activity to spoken words.

I am many.

A dark ambient journey through feeling lost, detached, and emotionally numb.

use this mix for late-night thoughts, study, writing, sleep or to to calm down.

→▫️support me on ko-fi: https://ko-fi.com/blackridge.

→ download on bandcamp: https://blackridgeofficial.bandcamp.com/track/i-dont-recognize-myself-anymore.

→ get the wallpapers: https://ko-fi.com/s/a9d71bee15

#darkambient #backrooms #sad #liminalspace #sleep.

All audio has been modified, mixed, and mastered by blackridge.