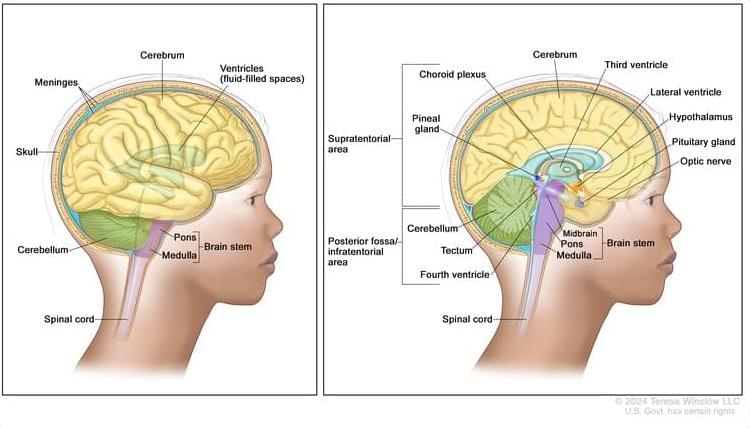

From birth to the last moments of life, the human brain is known to change and evolve significantly, both in terms of its physical organization (i.e., structural connectivity) and the coordination between different brain regions (i.e., functional connectivity). Mapping and understanding the brain’s evolution over time is of crucial importance, as it could also shed light on differences in the brains of individuals who develop various mental health disorders or experience an aging-related cognitive decline.

Researchers at Beijing Normal University and other institutes in China recently carried out a large-scale study to gather new insights into how the brain’s functional connectivity of humans worldwide changes over the course of their lifespan. Their paper, published in Nature Neuroscience, unveils patterns in the evolution of the brain that could inform future research focusing on a wide range of neuropsychiatric and cognitive disorders.

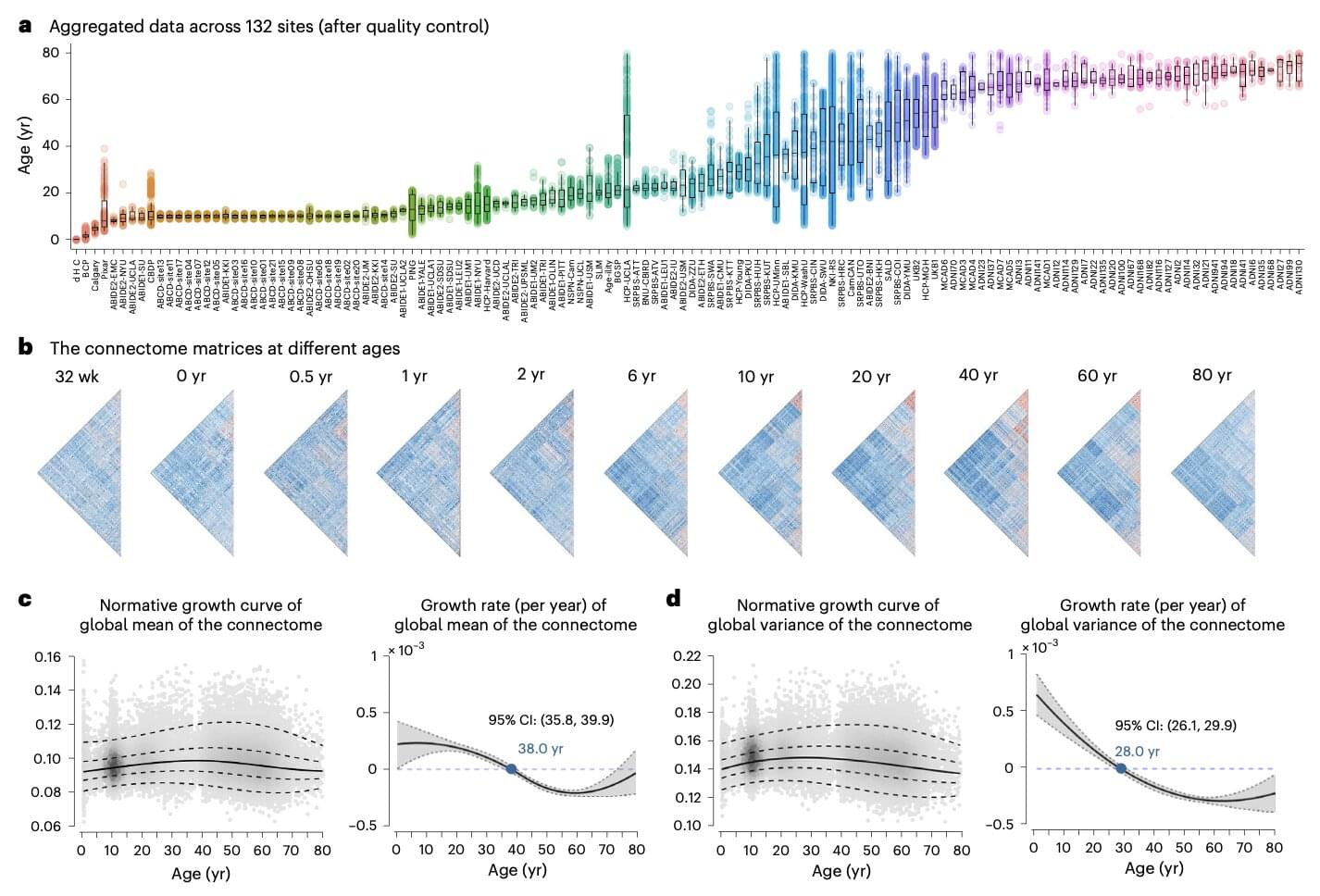

“Functional connectivity of the human brain changes through life,” wrote Lianglong Sun, Tengda Zhao and their colleagues in their paper. “We assemble task-free functional and structural magnetic resonance imaging data from 33,250 individuals at 32 weeks of postmenstrual age to 80 years from 132 global sites.”