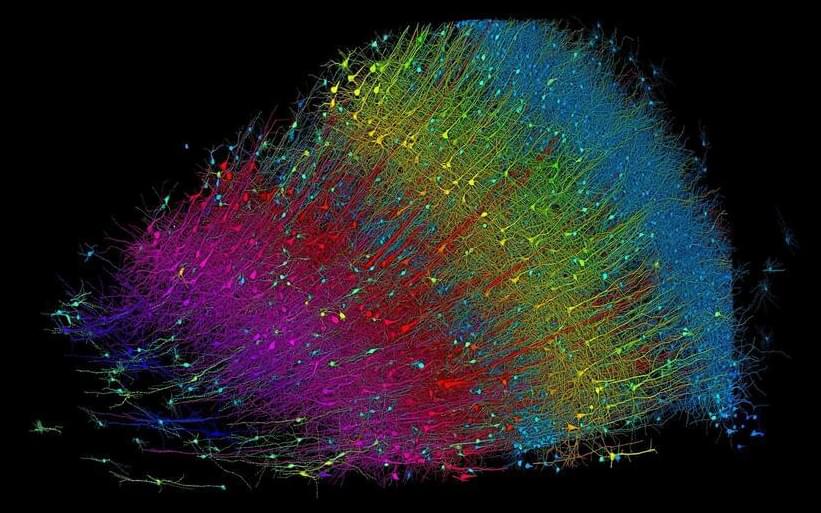

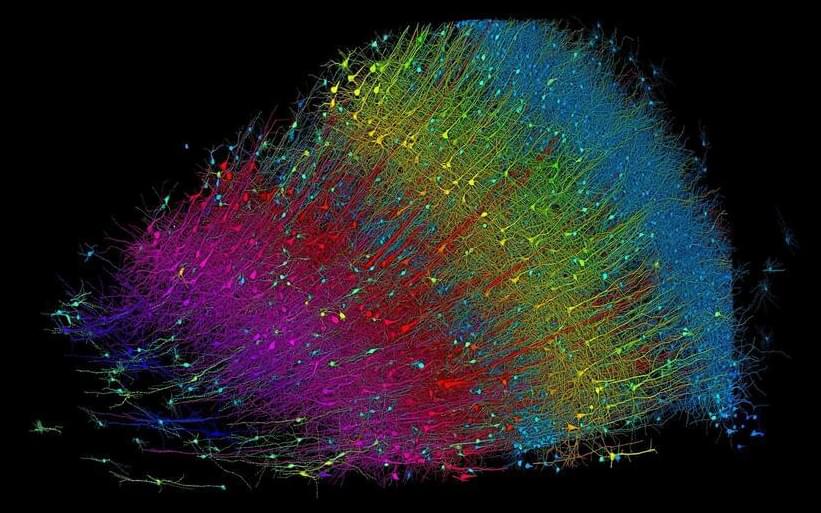

A collaborative effort between Harvard and Google has led to a breakthrough in brain science, producing an extensive 3D map of a tiny segment of human brain, revealing complex neural interactions and laying the groundwork for mapping an entire mouse brain.

A cubic millimeter of brain tissue may not sound like much. But considering that tiny square contains 57,000 cells, 230 millimeters of blood vessels, and 150 million synapses, all amounting to 1,400 terabytes of data, Harvard and Google researchers have just accomplished something enormous.

A Harvard team led by Jeff Lichtman, the Jeremy R. Knowles Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biology and newly appointed dean of science, has co-created with Google researchers the largest synaptic-resolution, 3D reconstruction of a piece of human brain to date, showing in vivid detail each cell and its web of neural connections in a piece of human temporal cortex about half the size of a rice grain.