Found on Google from livescience.com

Found on Google from livescience.com

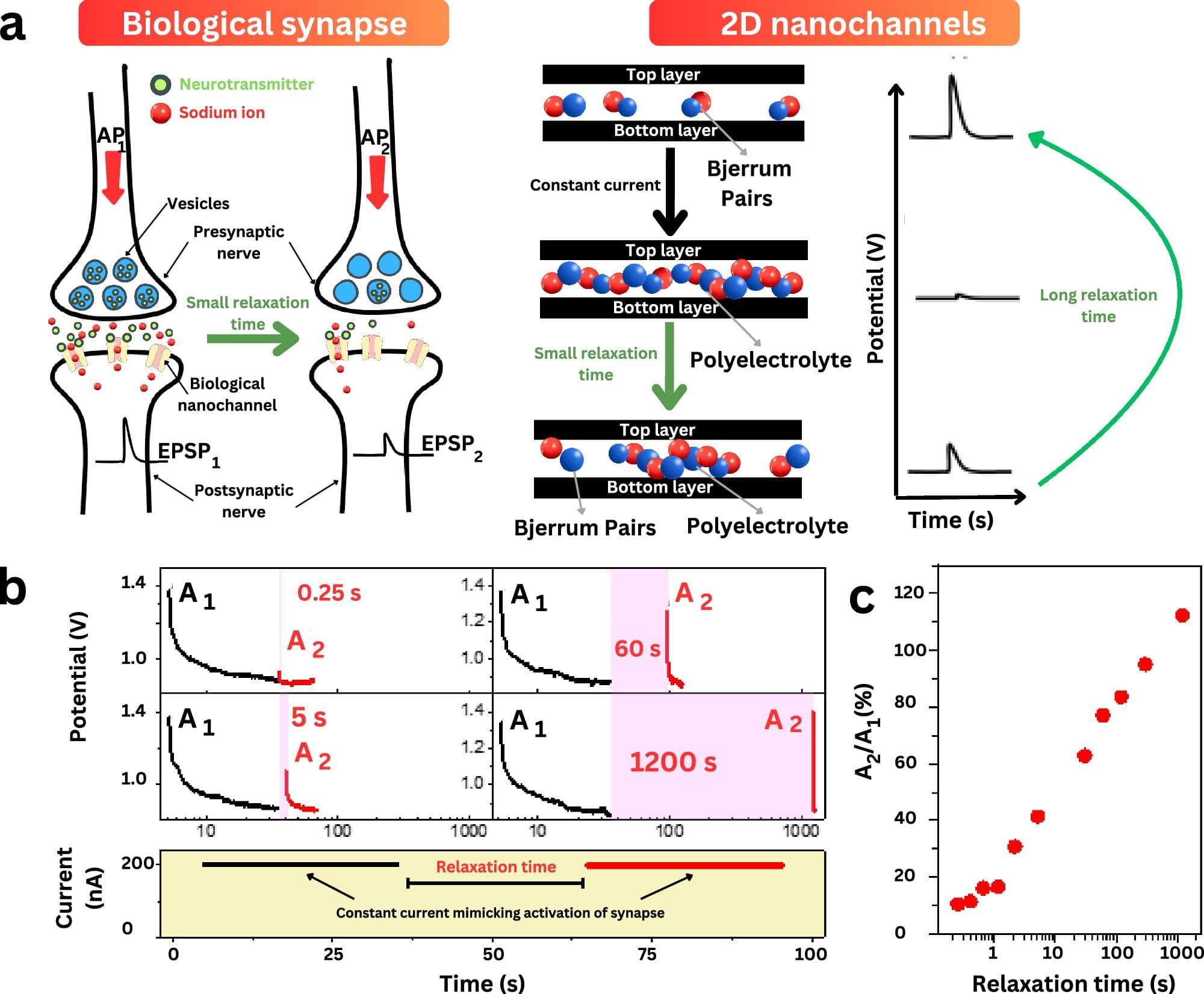

Researchers at The University of Manchester’s National Graphene Institute have developed a new class of programmable nanofluidic memristors that mimic the memory functions of the human brain, paving the way for next-generation neuromorphic computing.

In a study published in Nature Communications, scientists from the National Graphene Institute, Photon Science Institute and the Department of Physics and Astronomy have demonstrated how two-dimensional (2D) nanochannels can be tuned to exhibit all four theoretically predicted types of memristive behavior, something never before achieved in a single device.

This study not only reveals new insights into ionic memory mechanisms but also has the potential to enable emerging applications in low-power ionic logic, neuromorphic components, and adaptive chemical sensing.

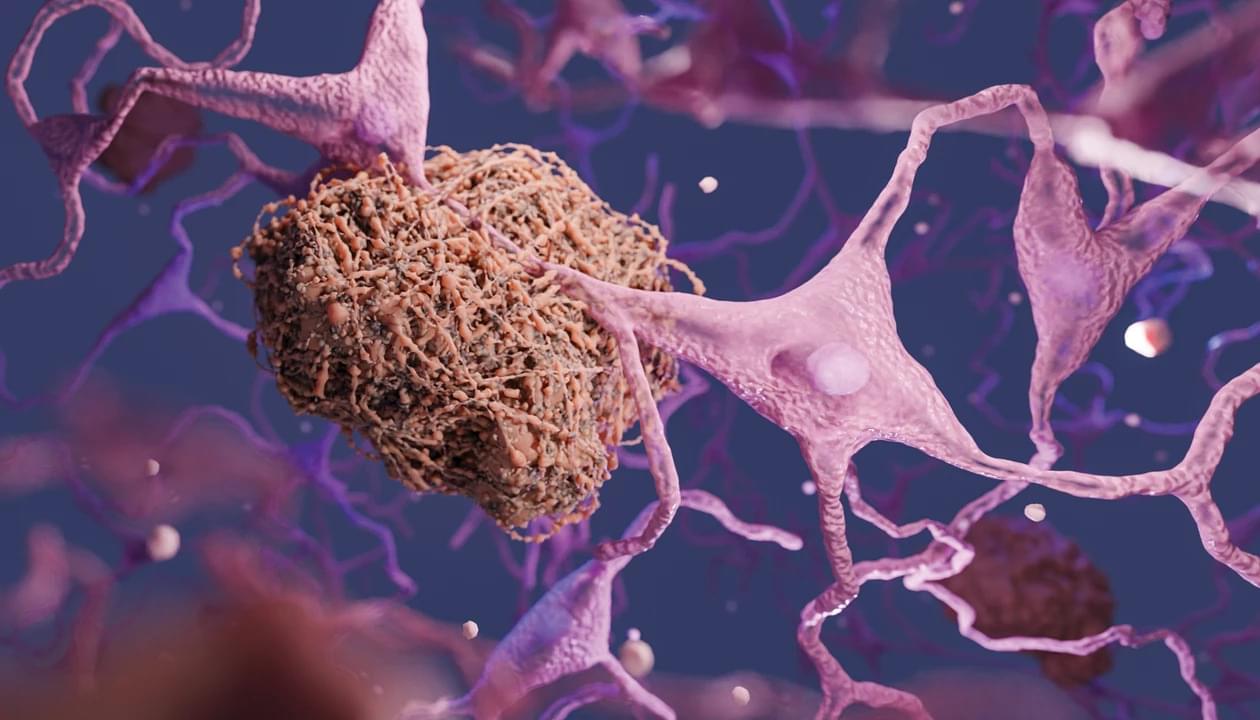

For 25 years, scientists at Northwestern Medicine have been studying people aged 80 years and older – dubbed “SuperAgers” – to uncover what makes them stand out.

In a new study, researchers show that these individuals display memory performance comparable to those at least 30 years younger, defying the long-held belief that cognitive decline is an unavoidable part of aging.

The study was published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

The human brain builds mental representations of the world based on the signals and information detected via the human senses. While we perceive simultaneously occurring sensory stimuli as being synchronized, the generation and transmission speeds of individual sensory signals can vary greatly.

Researchers at the Institute of Molecular and Clinical Ophthalmology Basel (IOB), University of Basel and Eidgenossische Technische Hochschule (ETH) Zurich recently carried out a study aimed at better understanding how the human visual system achieves this synchronization, regardless of the speed at which visual signals travel. Their paper, published in Nature Neuroscience, reports a previously unknown mechanism through which the retina synchronizes the arrival times of different visual signals.

“We can see because photoreceptors in the retina at the back of our eyes detect light and encode information about the visual world in the form of electrical signals,” Felix Franke and Annalisa Bucci, senior author and first author of the paper, respectively, told Medical Xpress.