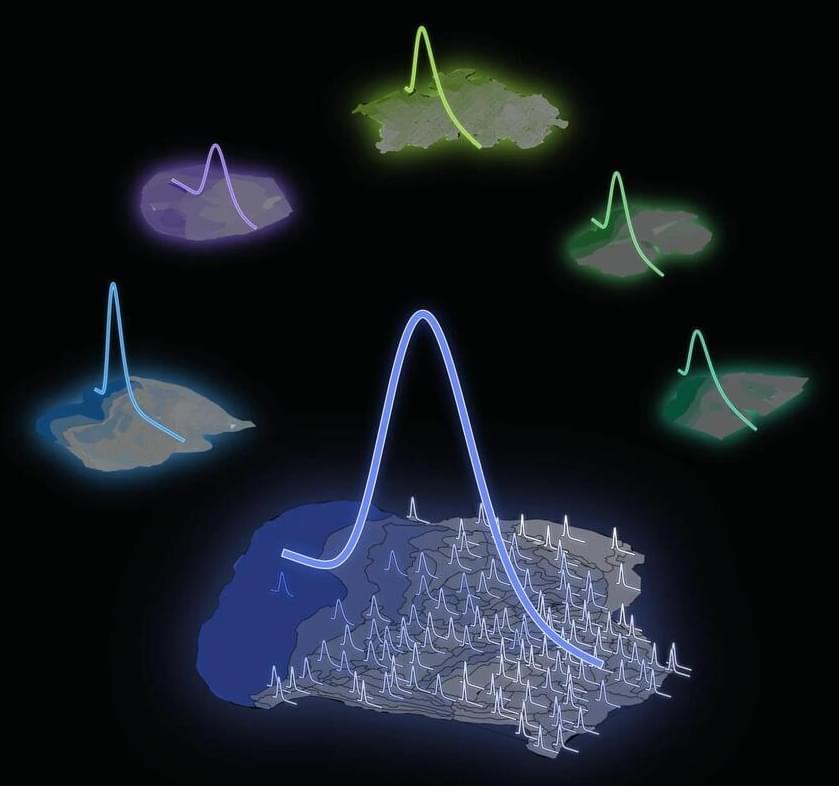

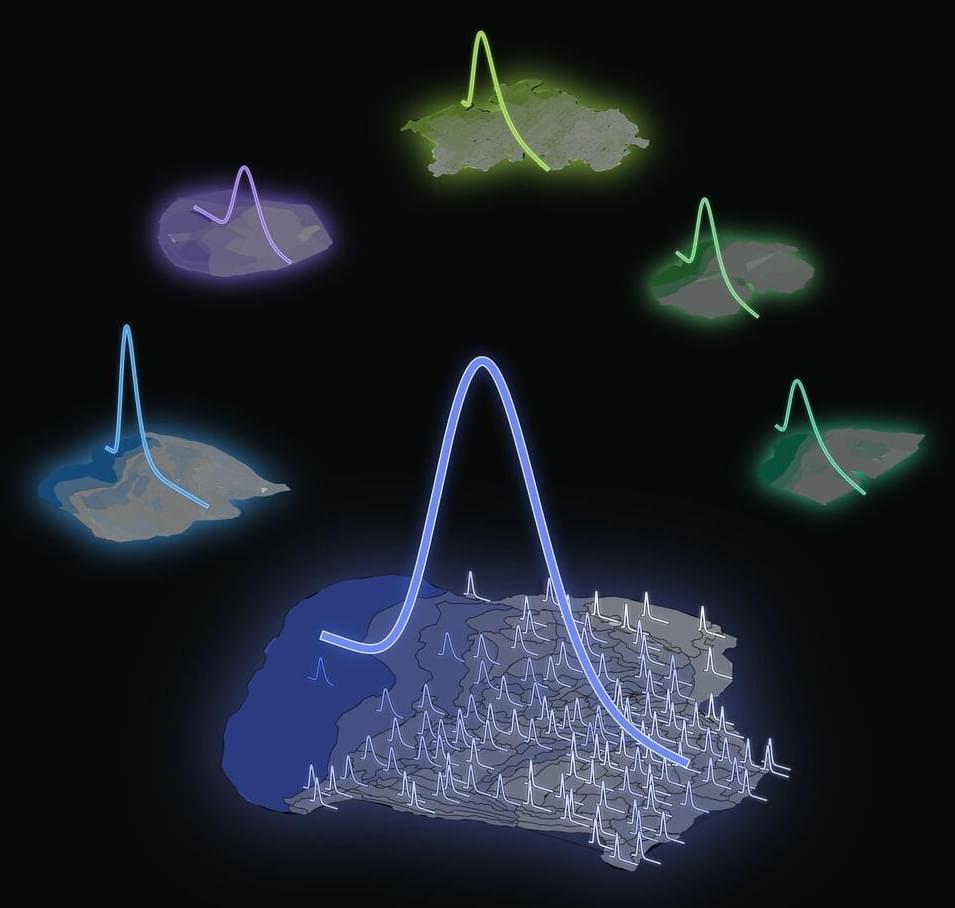

Human Brain Project researchers from Forschungszentrum Jülich and the University of Cologne (Germany) have uncovered how neuron densities are distributed across and within cortical areas in the mammalian brain. They have unveiled a fundamental organizational principle of cortical cytoarchitecture: the ubiquitous lognormal distribution of neuron densities.

Numbers of neurons and their spatial arrangement play a crucial role in shaping the brain’s structure and function. Yet, despite the wealth of available cytoarchitectonic data, the statistical distributions of neuron densities remain largely undescribed. The new Human Brain Project (HBP) study, published in the journal Cerebral Cortex, advances our understanding of the organization of mammalian brains.

Analyzing the datasets and the lognormal distribution.