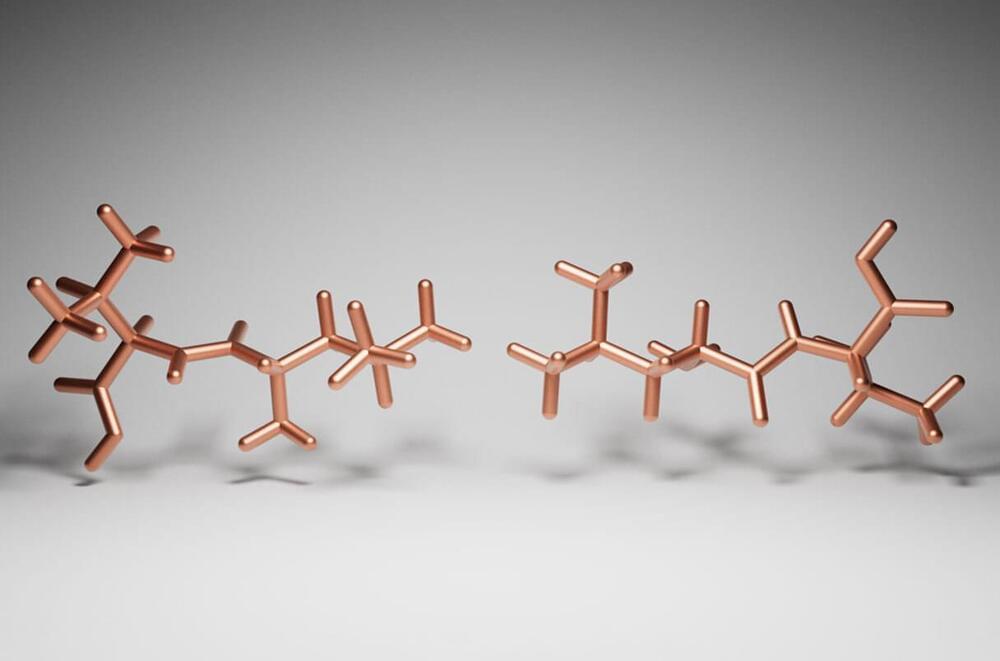

At the end of the 20th century, analog systems in computer science have been widely replaced by digital systems due to their higher computing power. Nevertheless, the question keeps being intriguing until now: is the brain analog or digital? Initially, the latter has been favored, considering it as a Turing machine that works like a digital computer. However, more recently, digital and analog processes have been combined to implant human behavior in robots, endowing them with artificial intelligence (AI). Therefore, we think it is timely to compare mathematical models with the biology of computation in the brain. To this end, digital and analog processes clearly identified in cellular and molecular interactions in the Central Nervous System are highlighted. But above that, we try to pinpoint reasons distinguishing in silico computation from salient features of biological computation. First, genuinely analog information processing has been observed in electrical synapses and through gap junctions, the latter both in neurons and astrocytes. Apparently opposed to that, neuronal action potentials (APs) or spikes represent clearly digital events, like the yes/no or 1/0 of a Turing machine. However, spikes are rarely uniform, but can vary in amplitude and widths, which has significant, differential effects on transmitter release at the presynaptic terminal, where notwithstanding the quantal (vesicular) release itself is digital. Conversely, at the dendritic site of the postsynaptic neuron, there are numerous analog events of computation. Moreover, synaptic transmission of information is not only neuronal, but heavily influenced by astrocytes tightly ensheathing the majority of synapses in brain (tripartite synapse). At least at this point, LTP and LTD modifying synaptic plasticity and believed to induce short and long-term memory processes including consolidation (equivalent to RAM and ROM in electronic devices) have to be discussed. The present knowledge of how the brain stores and retrieves memories includes a variety of options (e.g., neuronal network oscillations, engram cells, astrocytic syncytium). Also epigenetic features play crucial roles in memory formation and its consolidation, which necessarily guides to molecular events like gene transcription and translation. In conclusion, brain computation is not only digital or analog, or a combination of both, but encompasses features in parallel, and of higher orders of complexity.

Keywords: analog-digital computation; artificial and biological intelligence; bifurcations; cellular computation; engrams; learning and memory; molecular computation; network oscillations.

Copyright © 2023 Gebicke-Haerter.