From the article:

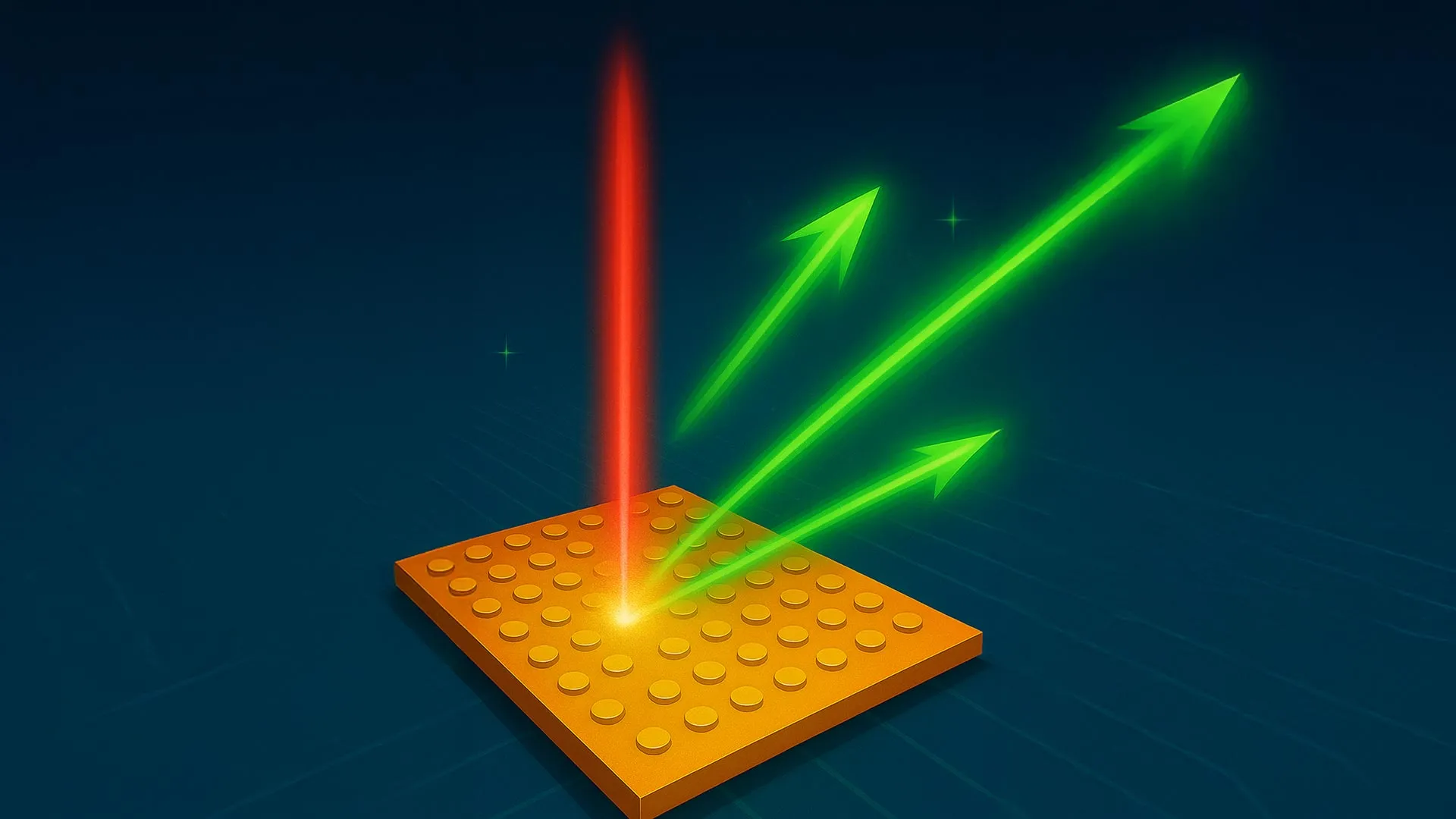

…in copper, the transition was extremely fast, taking about 26 attoseconds.

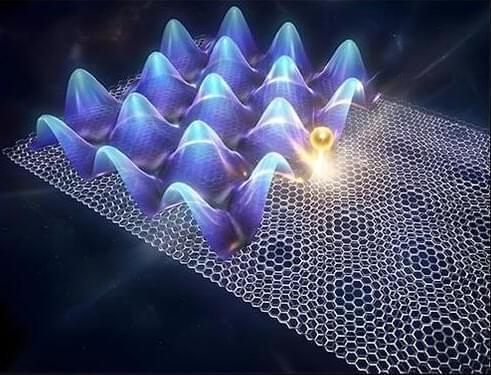

In the layered materials TiSe₂ and TiTe₂, the same process slowed to between 140 and 175 attoseconds. In CuTe, with its chain-like structure, the transition exceeded 200 attoseconds. These findings show that the atomic scale shape of a material strongly affects how quickly a quantum event unfolds, with lower symmetry structures leading to longer transition times.

Time may feel smooth and continuous, but at the quantum level it behaves very differently. Physicists have now found a way to measure how long ultrafast quantum events actually last, without relying on any external clock. By tracking subtle changes in electrons as they absorb light and escape a material, researchers discovered that these transitions are not instantaneous and that their duration depends strongly on the atomic structure of the material involved.