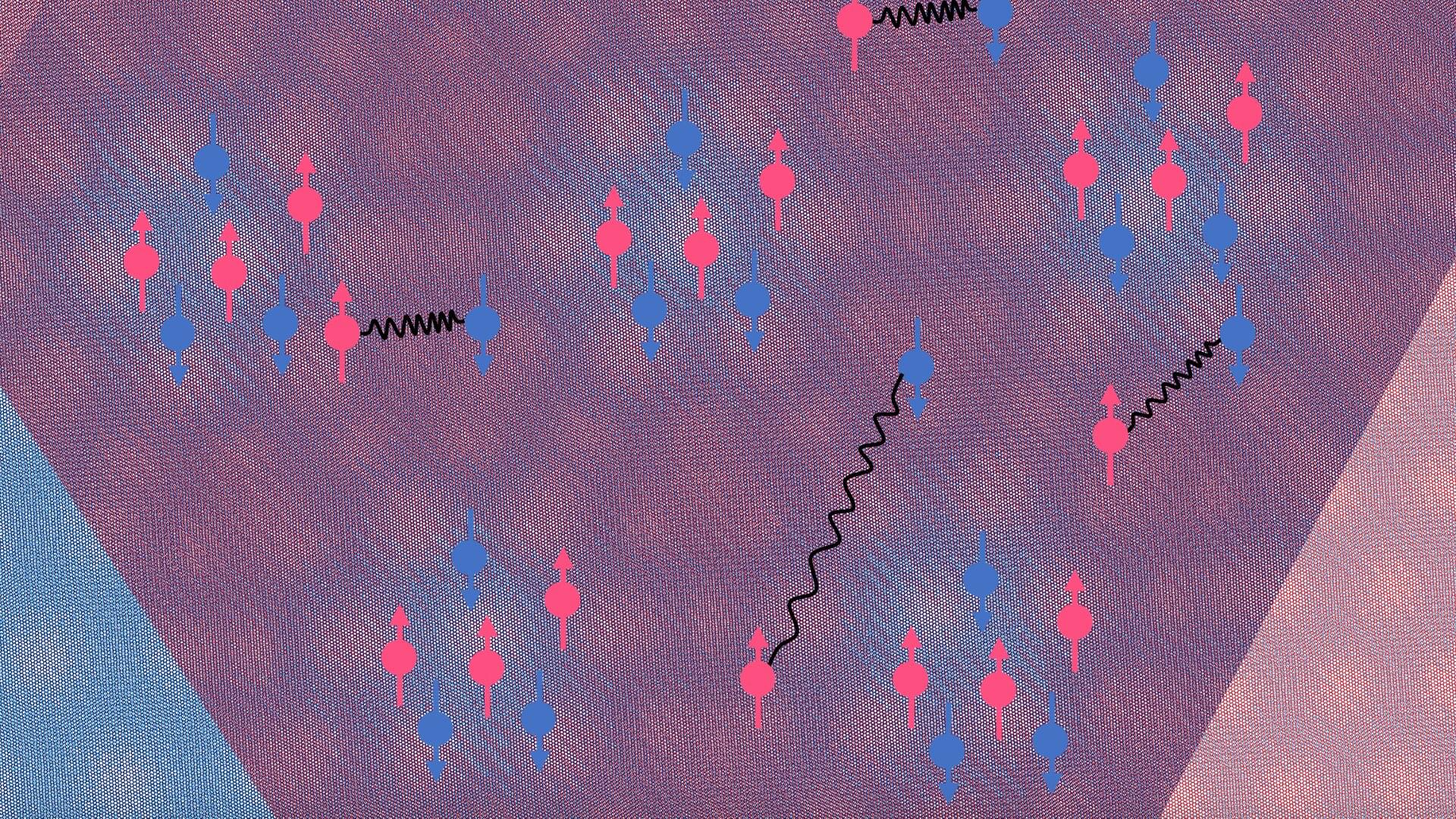

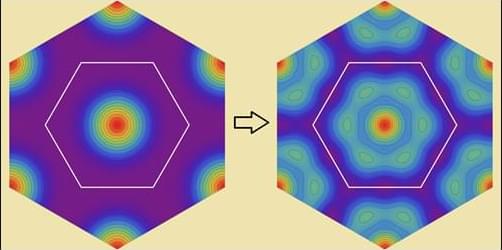

Two or more graphene layers that are stacked with a small twist angle in relation to each other form a so-called moiré lattice. This characteristic pattern influences the movement of electrons inside materials, which can give rise to strongly correlated states, such as superconductivity.

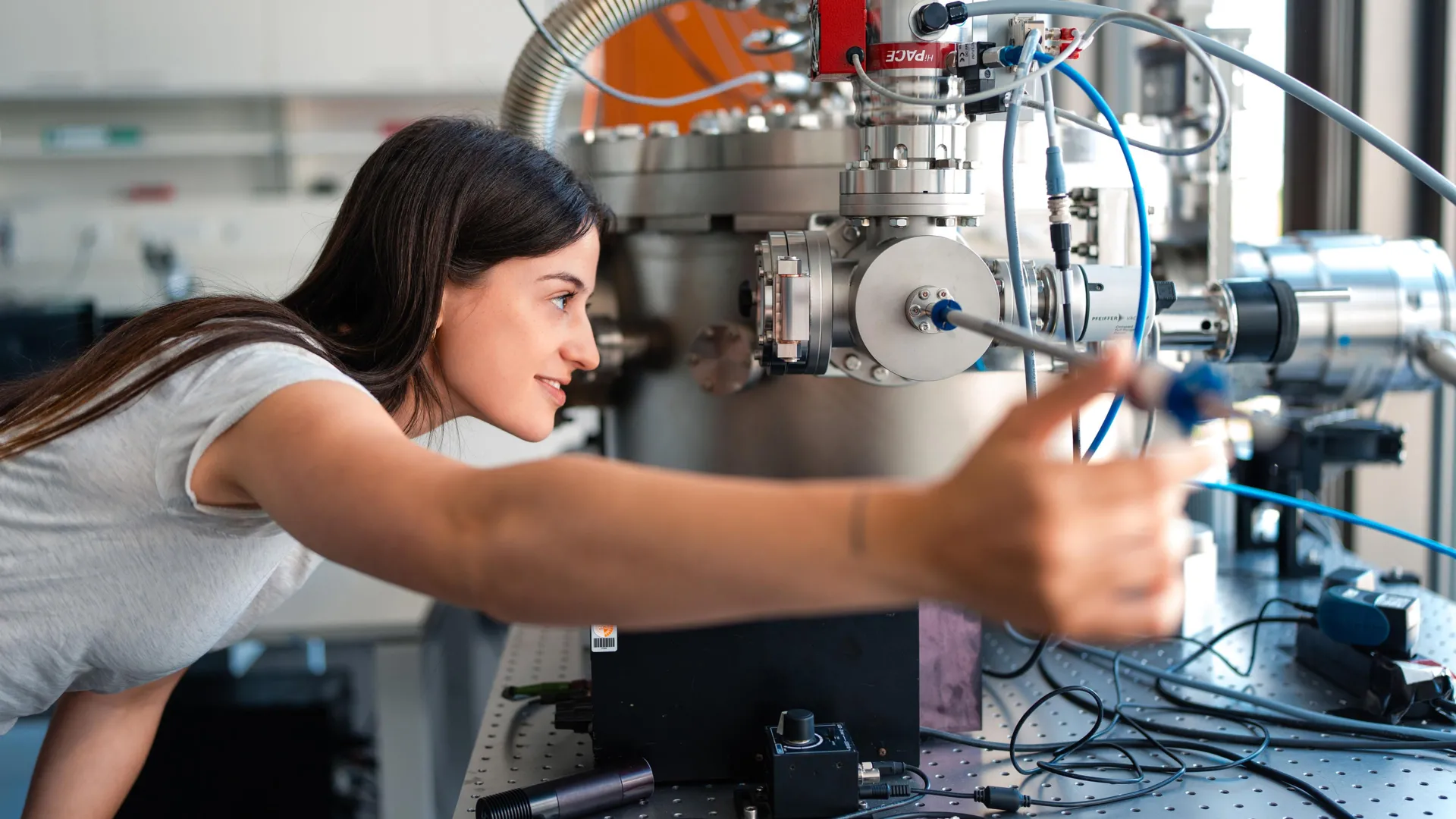

Researchers at Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Freie Universität Berlin and other institutes recently uncovered a strong superconductivity in a supermoiré lattice, a twisted trilayer graphene structure with broken symmetry in which several moiré patterns overlap. Their paper, published in Nature Physics, could open new possibilities for the design of quantum materials for various applications.

“Fabricating a twisted trilayer graphene device with two distinct twist angles was not our original intention,” Mitali Banerjee, senior author of the paper, told Phys.org. “Instead, we aimed to make a device in which the two twist angles are identical in magnitude (magic-angle twisted trilayer). During our measurements, however, my student Zekang Zhou found that the phase diagram of this device differs fundamentally from that of magic-angle twisted trilayer graphene.”