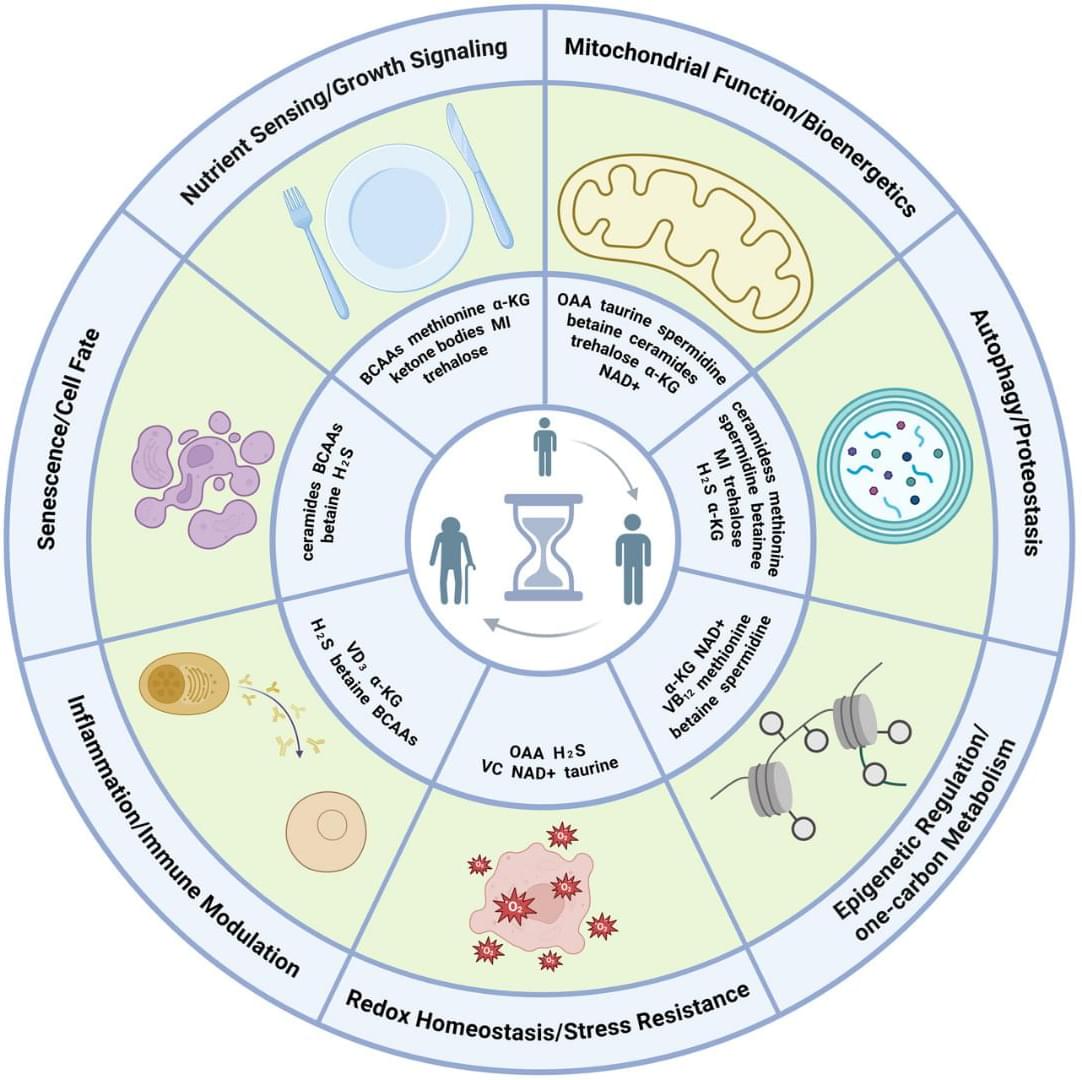

Endogenous metabolites are small molecules produced by an organism’s own metabolism. They encompass a wide range of molecules, such as amino acids, lipids, nucleotides, and sugars, which are pivotal for cellular function and organismal health (Baker and Rutter 2023). Beyond serving as biosynthetic precursors and energy substrates, many metabolites also function as dynamic modulators of signaling and gene regulatory networks by engaging in protein–metabolite interactions, allosteric regulation, and by serving as substrates for chromatin and other post-translational modifications (Boon et al. 2020 ; Hornisch and Piazza 2025). Metabolites can function as extracellular signals activating G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), such as free fatty acid receptors for fatty acids, GPR81 for lactate, SUCNR1 for succinate, and TGR5 for bile acids (Tonack et al. 2013). These GPCRs are expressed in gut, adipose tissue, endocrine glands, and immune cells, linking nutrient and metabolite levels to diverse physiological responses (Tonack et al. 2013). Other metabolites serve as enzyme cofactors or epigenetic regulators. For example, methyl donors like betaine provide methyl groups for DNA and histone methylation and also act as osmolytes to protect cells under stress (Lever and Slow 2010). Some metabolites even form specialized structural assemblies. For instance, guanine crystals can form structural color in feline eyes and contribute to enhanced night vision (Aizen et al. 2018).

Perturbations of endogenous metabolite levels or fluxes have been linked to genomic instability, metabolic dysfunction, and age-related diseases, motivating study of metabolites as both biomarkers and functional modulators of aging (Adav and Wang 2021 ; Tomar and Erber 2023 ; Xiao et al. 2025). Metabolomic studies reveal characteristic metabolite changes in diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Panyard et al. 2022), suggesting that metabolites not only reflect organismal state but also can actively influence aging pathways. In subsequent sections, we will examine specific endogenous metabolites implicated in longevity regulation.