I’ve just hopped on a video call with the CEO of Retro Biosciences, the Sam Altman-backed longevity company, when I mention it’s quite hot.

Joe Betts-LaCroix takes my passing comment as a cue to muse on the wonders of air conditioning, and how energy and heat were once synonymous — until they weren’t.

As a multi-hyphenate scientist, entrepreneur, and once-inventor of the world’s smallest computer, Betts-LaCroix is excited by paradigm change.

At the helm of what is essentially Altman’s playground for experimenting with pushing the limits of the human lifespan, Betts-LaCroix is hoping to engineer the same shift that air conditioning brought to hot summer days for your brain and body. Ideally, one day, decouple aging from decline and disease.

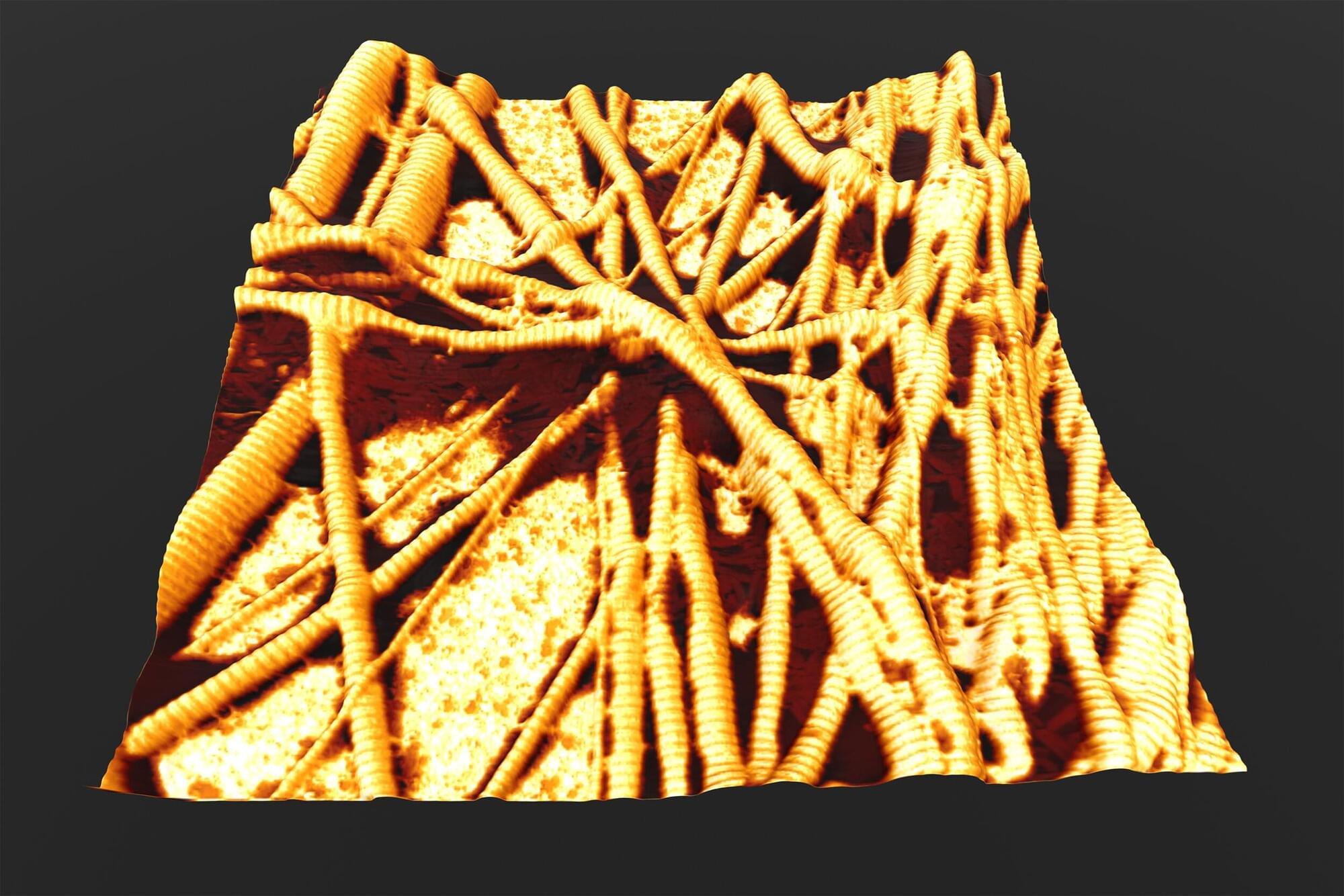

The experimental memory pill works by clearing out “gunk in the cells” linked to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, Betts-LaCroix said. If the pill works, it will restart stalled autophagy processes in the body, cleaning up damage, “especially in the brain cells,” he said.

In contrast, other new Alzheimer’s drugs, like Eisai’s Leqembi and Eli Lilly’s Kisunla, slow down cognitive decline by flushing out sticky amyloid plaques that are a hallmark of the disease.