DNA methylation plays a critical role in gene expression regulation and has emerged as a robust biomarker of biological age. This modification will become heavier or site drift along with aging. Recently, it is termed epigenetic clocks—such as Horvath, Hannum, PhenoAge, and GrimAge—leverage specific methylation patterns to accurately predict age-related decline, disease risk, and mortality. These tools are now widely applied across diverse tissues, populations, and disease contexts. Beyond age-related loss of methylation control, accelerated DNA methylation age has been linked to environmental exposures, lifestyle factors, and chronic diseases, further reinforcing its value as a dynamic and clinically relevant marker of biological aging. DNA methylation is reshaping our understanding of aging and disease risk, with promising implications for preventive medicine and interventions aimed at promoting healthy longevity. However, it must be admitted that some challenges remain, including limited generalizability across populations, an unclear mechanism, and inconsistent longitudinal performance. In this review, we examine the biological foundations of DNA methylation, major advances in epigenetic clock development, and their expanding applications in aging research, disease prediction and health monitoring.

Aging is a complex, multifactorial process that affects nearly all biological systems. While chronological age simply measures the passage of time from birth, biological age reflects the functional state and health of an individual’s tissues and organs (Kiselev et al., 2025). This distinction is critical, as individuals of the same chronological age often exhibit markedly different biological conditions, disease risks, and mortality trajectories (Dugue et al., 2018). Therefore, biological age potentially serves as a more meaningful measure of aging-related decline and is increasingly used to assess overall health status, predict disease onset, and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions aimed at promoting healthy longevity (Dugue et al., 2018; Petkovich et al., 2017).

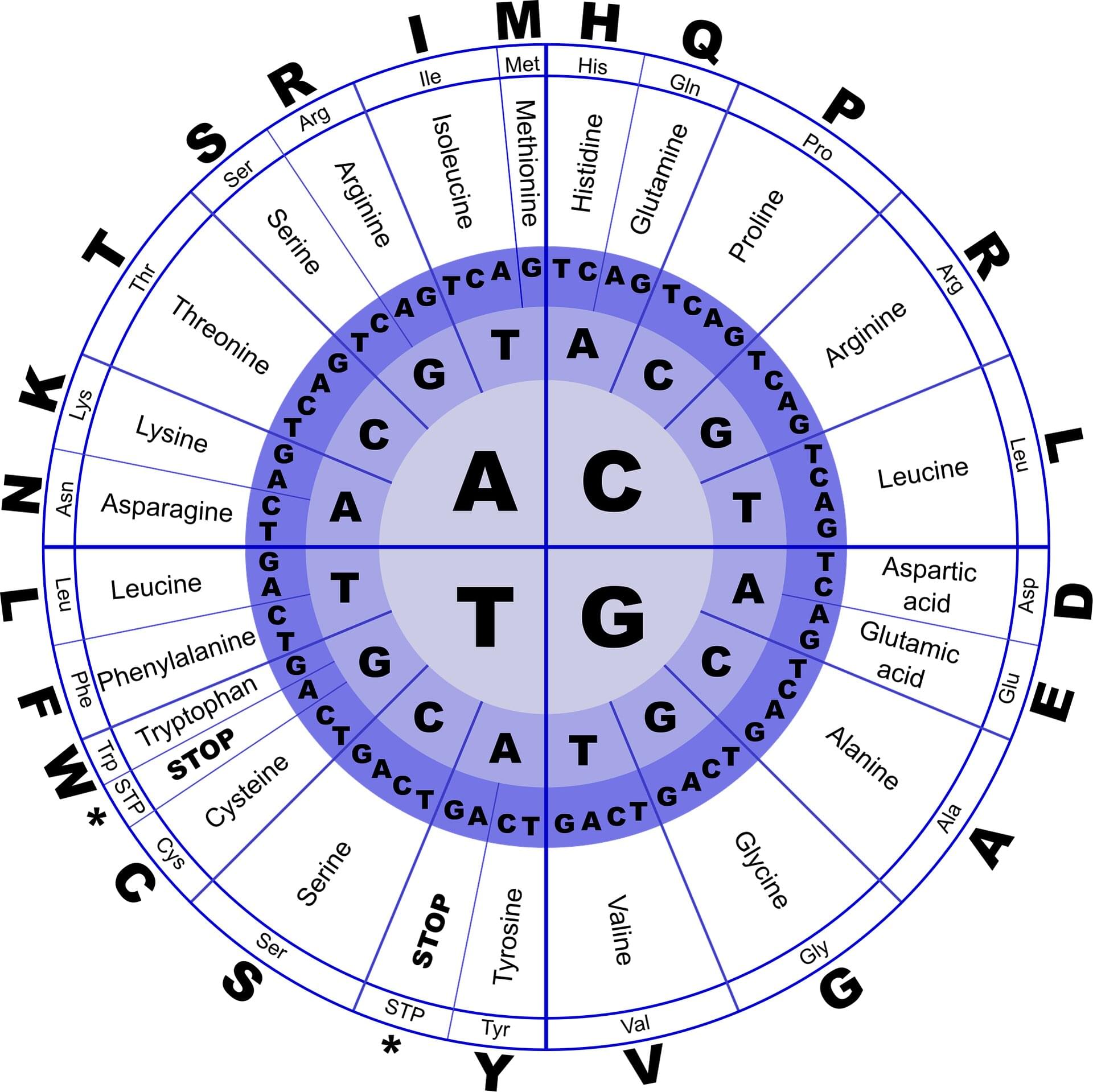

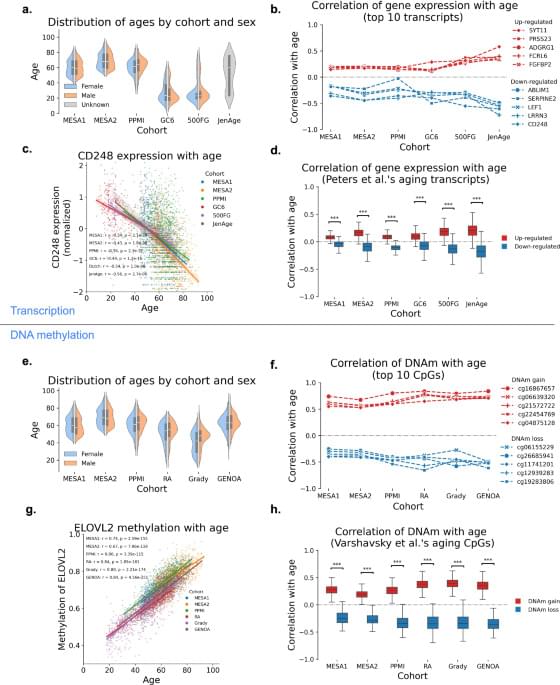

Among various biomarkers proposed to estimate biological age, epigenetic modifications—particularly DNA methylation—have emerged as one of the most reliable and informative (Dugue et al., 2018). In epigenetics, DNA methylation involves the addition of a methyl group to the 5′ position of cytosine residues, typically at CpG dinucleotides, which can regulate gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. Moreover, DNA methylation can be accurately measured by sequencing at methylated sites with bisulfate treatment (Zhang et al., 2012). Age-related changes in DNA methylation pattern are not random; they occur at specific genomic locations. These methylated sites are picked and constitute come patterns, by which scientists can construct “epigenetic clocks” to precisely estimate a person’s biological age based on their DNA modification. As people grow older, their methylation profiles shift in predictable ways (Kiselev et al., 2025; Horvath, 2013; Horvath and Raj, 2018).