Rodents are considered one of the animal pests with the greatest impact on agricultural production and public health, especially the brown or Norway rat (Rattus norvegicus), the black or roof rat (Rattus rattus) and the house mouse (Mus musculus). Its control is an increasing problem worldwide. The intensification of agricultural production methods as well as the increase in merchandise transport to sustain growing populations is leading to an increase in waste production causing the growth of these rodent populations. The estimated losses in crop production caused by rodents range from between 5% and 90% (Stenseth et al., 2003) and this can cause problems in food security during harvesting (Belmain et al., 2015). Other negative impacts result from some rodent species living very close to human environments that can have a direct influence not only on human health through potential transmission of gastroenteric diseases and zoonosis to householders but also on domestic livestock. Therefore, rodent pest control is crucial and nowadays, the only effective control method available is the use of anticoagulant rodenticides (ARs).

ARs are so named because they interfere with the blood coagulation processes. The processes of activating various coagulation factors depends on the amount of vitamin K in its reduced form that exists in the organism. ARs inhibit the enzyme vitamin K 2,3-epoxide reductase (VKORC1) that is responsible for reducing vitamin K and maintaining the balance between its oxidized and reduced forms. The inhibition of VKORC1 prevents the activation of the coagulation factors resulting in animal death by internal bleeding. However, the intensive use of ARs can cause rodents to lose their susceptibility and become resistant to them. Genetic resistances to ARs are mainly associated with mutations or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the gene that codes for VKORC1 (vkorc1), causing amino acid substitutions in the VKORC1 protein ( Pelz et al., 2005 ). There are studies on this topic in several countries of central and northern Europe detecting rodent populations resistant to AR. Currently, there are at least 13 mutations mainly located in the exon 3 of the vkorc1 gene described in various countries of the European Union that confer resistance to specific ARs ( Berny et al., 2014 ; Goulois et al., 2017 ). In Eastern and Southern European countries, the information on the incidence of resistances to rodenticides is scarce, and it is becoming increasingly important to generate information on this subject ( Berny et al., 2014). In Spain, a mice population at the coastal countryside showing an adaptive introgression between house mouse and Algerian mouse that confers anticoagulant resistance has been described ( Song et al., 2011 ). While recently, four VKORC1 mutations in black rat were found in Toledo, Segovia and Zaragoza ( Goulois et al., 2016 ; Damin-Pernik et al., 2022 ). Any increase in resistant in rodent populations would lead to pest control issues that may causing serious agricultural, farming and public health problems.

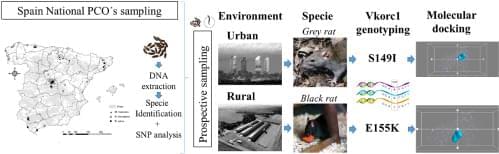

Scientific advances have revolutionized the study of anticoagulant resistances in terms of understanding their genetic basis, physiological mechanisms and geographical distribution. The techniques based on the extraction and partial sequencing of genomic DNA allow a fast and precise monitoring of possible genetic resistances. Most of these tests involve laboratory studies using live rodents or blood samples taken from animals in the field. However, the improvement of DNA extraction techniques now allows the analysis of faecal samples (stool), increasing the number of samples that can be taken without the need for sampling by trapping or the management of dead animals (Meerburg et al., 2014). The importance of initial detection of genetic resistances due to mutations is crucial. The hypothesis of work, presenting it as a null hypothesis, is that there will be no rodent mutations in the vkorc1 gene in Spain.