Scientists reveal how the Dsup protein found in tardigrades protects DNA from extreme radiation, which is key for future space missions.

This attack is notable not least because it obviates the need for an attacker to send an RST_STREAM frame, thereby completely bypassing Rapid Reset mitigations, and also achieves the same impact as the latter.

In an advisory, the CERT Coordination Center (CERT/CC) said MadeYouReset exploits a mismatch caused by stream resets between HTTP/2 specifications and the internal architectures of many real-world web servers, resulting in resource exhaustion — something an attacker can exploit to induce a DoS attack.

Discover how to create AI experiences with Copilot Studio and build low-code solutions using Microsoft Power Platform. Join the Microsoft Power Up Program today and get ready for the future of work.

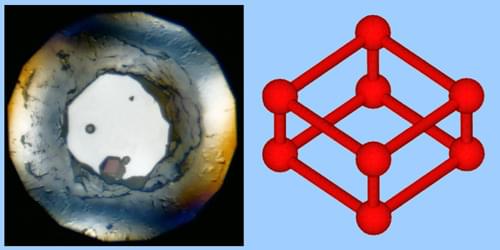

Cobras kill thousands of people a year worldwide and perhaps a hundred thousand more are seriously maimed by necrosis – the death of body tissue and cells – caused by the venom, which can lead to amputation.

Current antivenom treatment is expensive and does not effectively treat the necrosis of the flesh where the bite occurs.

“Our discovery could drastically reduce the terrible injuries from necrosis caused by cobra bites – and it might also slow the venom, which could improve survival rates,” said Professor Greg Neely, a corresponding author of the study from the Charles Perkins Centre and Faculty of Science at the University of Sydney.

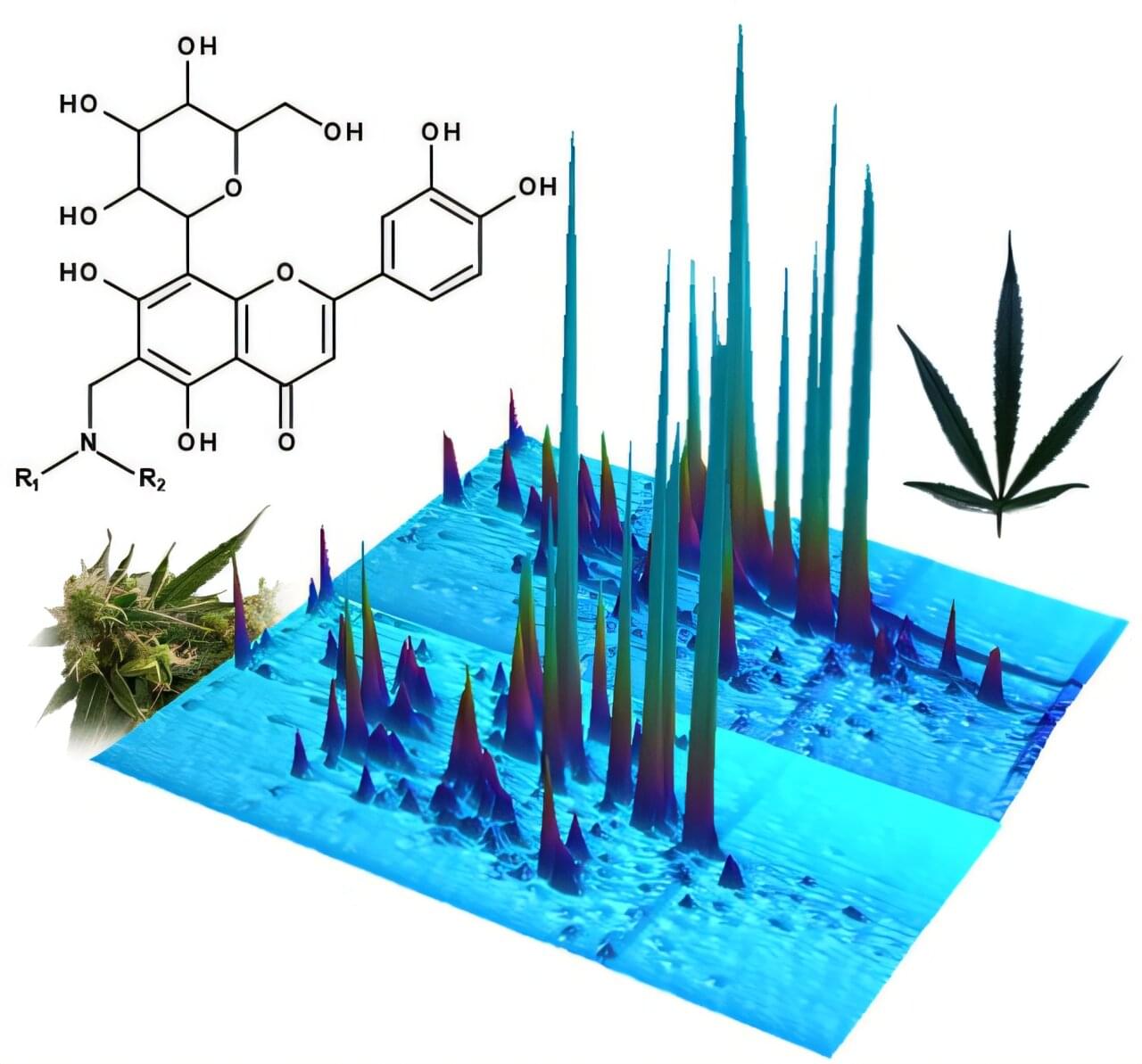

Analytical chemists from Stellenbosch University (SU) have provided the first evidence of a rare class of phenolics, called flavoalkaloids, in cannabis leaves.

Phenolic compounds, especially flavonoids, are well-known and sought after in the pharmaceutical industry because of their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-carcinogenic properties.

The researchers identified 79 phenolic compounds in three strains of cannabis grown commercially in South Africa, of which 25 were reported for the first time in cannabis. Sixteen of these compounds were tentatively identified as flavoalkaloids. Interestingly, the flavoalkaloids were mainly found in the leaves of only one of the strains. The results were published in the Journal of Chromatography A recently.