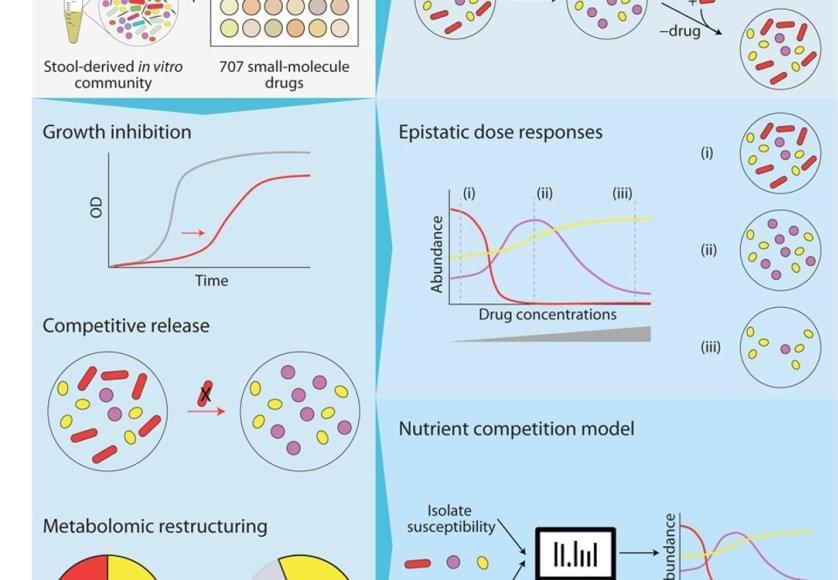

The bacteria in our poop are a reasonable representation of what’s living in our digestive system. To understand how different drugs can impact the gut microbiome, the team cultured microbial communities from nine donor fecal samples and systematically tested them with 707 different clinically relevant drugs.

The researchers examined changes in the growth of different bacterial species, the community composition, and the metabolome – the mix of small molecules called metabolites that microbes produce and consume. They found that 141 drugs altered the microbiome of the samples and even short-term treatments created enduring changes, entirely wiping out some microbial species. The primary force behind how the community responds to drug inhibition was competition over nutrients.

“The winners and losers among our gut bacteria can often be predicted by understanding how sensitive they are to the medications and how they compete for food,” said the first author on the paper. “In other words, drugs don’t just kill bacteria; they also reshuffle the ‘buffet’ in our gut, and that reshuffling shapes which bacteria win.”

Despite the complexity of the bacterial communities, the researchers were able to create data-driven computer models that accurately predicted how they would respond to a particular drug. They factored in the sensitivity of different bacterial species to that drug and the competitive landscape – essentially, who was competing with whom for which nutrients.

Their work provides a framework for predicting how a person’s microbial community might change with a given drug, and could help scientists find ways to prevent these changes or more easily restore a healthy gut microbiome in the future.

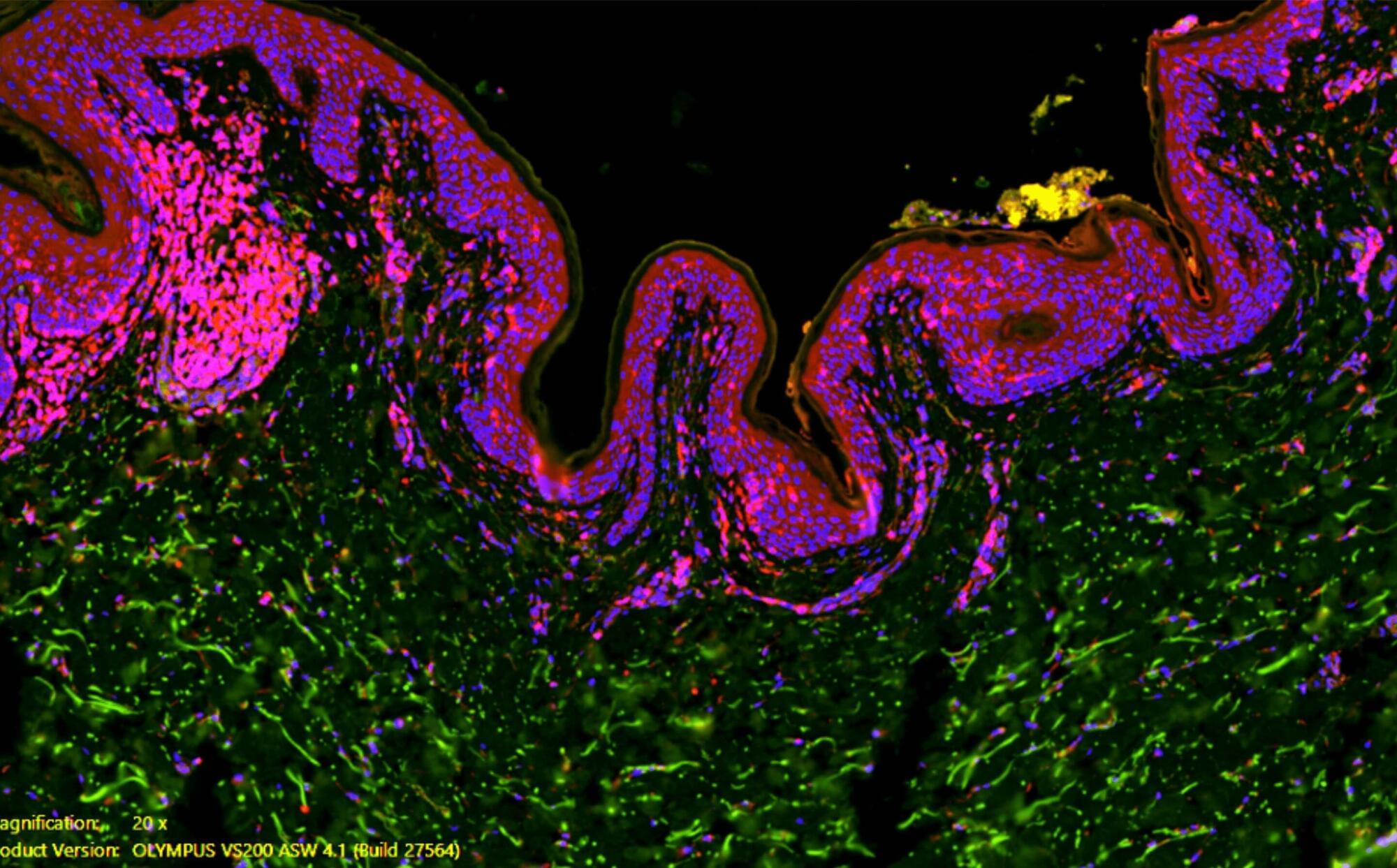

Our gut microbiome is made up of trillions of bacteria and other microbes living in our intestines. These help our bodies break down food, assist our immune system, send chemical signals to our brain, and potentially serve many other functions that researchers are still working to understand. When the microbiome is out of balance – with not enough helpful bacteria or the wrong combination of microbes – it can affect our whole body.