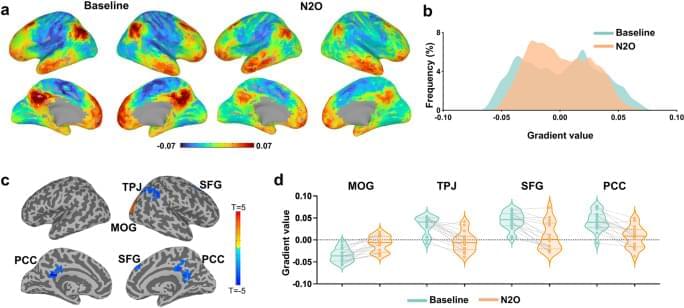

Cortical gradient mapping stands as an innovative analytical tool for exploring the brain’s functional-spatial organization along a continuous spectrum28,29,30, distinguishing it from conventional techniques reliant on discrete boundaries, e.g., functional parcellation in neuroimaging. As an intuitive metaphor, consider defining a geographic region by its boundary coordinates, which is akin to functional parcellation, versus describing it by elevation slopes or changes in vegetation types across various topographical axes, which is similar to gradient mapping. These cortical gradients span a wide spectrum of functions and networks, ranging from perception and action to higher-order cognitive processes28. Notably, Gradient-1, known as the unimodal to transmodal gradient, enables the integration of sensory signals with non-sensory data, transforming them into abstract content. Gradient-2, the visual to somatomotor gradient, represents the specialization of different sensory modalities. Lastly, Gradient-3 spans functional distinctions ranging from regions typically deactivated during task performance (i.e., task-negative) to those activated in frontoparietal and attention networks (i.e., task-positive)31,32. Despite promising foundations, the potential of gradients as a framework for analyzing and conceptualizing non-ordinary states of consciousness induced by psychedelics remains ripe for exploration.

In addition to the brain’s functional geometry, dynamic processes continuously mold and reconfigure functional arrangements, leading to the evolution of brain activity patterns over time33,34. Recent empirical investigations have highlighted the intricate interplay between the spatial and temporal characteristics of brain activity, emphasizing that a comprehensive understanding necessitates the consideration of both aspects. Notably, transient fMRI co-activations33,35,36 spanning the entire cortex have been observed to propagate like waves, following the spatially defined cortical gradients37,38,39. Consequently, temporal dynamics are likely to be influenced by the underlying functional geometry. Exploring the co-variation between these spatial and temporal factors holds the potential to offer deeper insights into the neural underpinnings of psychedelic effects.

The objective of this study was to apply advanced cortical gradient mapping and co-activation pattern analysis to dissect the brain’s spatiotemporal reconfiguration during the psychedelic experience induced by nitrous oxide. Building upon previous research findings16,25, we tested the hypothesis that nitrous oxide could diminish functional differentiation within the human cortex, as evidenced by a contraction in functional geometry and a disruption in temporal dynamics. We reanalyzed a neuroimaging dataset of healthy human volunteers, who were assessed by fMRI before and during exposure to psychedelic concentrations of nitrous oxide (35%, in oxygen) and who completed a validated altered states of consciousness questionnaire40 before and after drug exposure. We quantified the changes of neural activity in cortical gradients and co-activations; we also performed correlation analyses to explore the relationship between subjective psychedelic experience and these brain measures. We demonstrate that nitrous oxide flattens the functional geometry of the cortex and disrupts related temporal dynamics, particularly within the frontoparietal and somatomotor networks, in association with the psychedelic experience.