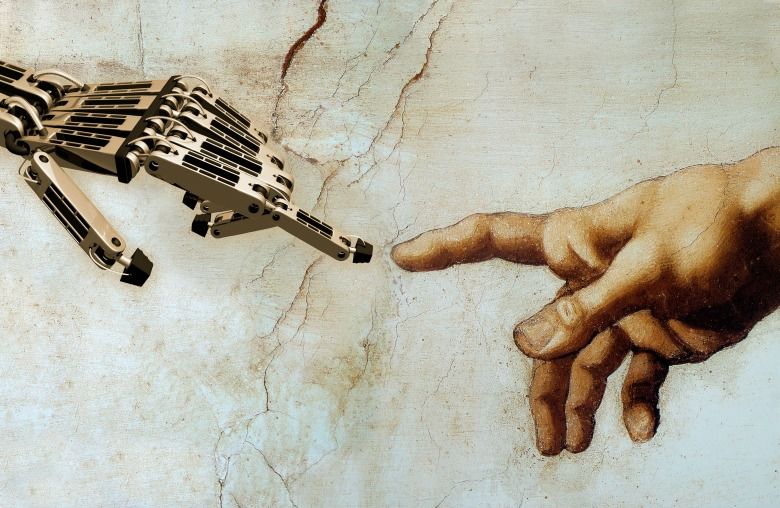

Exponential Fever. The business world is currently gripped by exponential fever. The concept came to prominence with Moore’s law — the doubling every 18–24 months of the amount of computer power available for $1,000. The phenomenon has since been replicated in many fields of science and technology. We now see the speed, functionality and performance of a range of technologies growing at an exponential rate – encompassing everything from data storage capacity and video download speed to the time taken to map a genome and the cost of producing a laboratory grown hamburger.

New Pretenders. A wave of new economy businesses has now brought exponential thinking to bear in transforming assumptions about how an industry works. For example, AirBnB handles roughly 90 times more bedroom listings per employee than the average hotel group, while Tangerine Bank can service seven times more customers than a typical competitor. In automotive, by adopting 3D printing, Local Motors can develop a new car model 1,000 times cheaper than traditional manufacturers, with each car coming ‘off the line’ 5 to 22 times faster. In response, businesses in literally every sector are pursuing exponential improvement in everything from new product development and order fulfillment through to professional productivity and the rate of revenue growth.

Stepping Up. For law firms, the transformation of other sectors and their accompanying legal frameworks creates a massive growth opportunity, coupled with the potential to bring similar approach to rethinking the way law firms operate. While some might be hesitant about applying these disruptive technologies internally, there is a clear opportunity to be captured from helping clients respond to these developments and from the creation of the industries of the future. To help bring to life the possibilities within legal, we highlight seven scenarios that illustrate how exponential change could transform law firms over the next 5 to 10 years.

Rise of the ‘Exponential Circle’. Our continuing programme of research on the future of law firms suggests that we will see exponential growth for those firms who can both master the legal implications of these technologies for their clients and become adept at their application within the firm. By 2025, we could indeed have witnessed the emergence of an Exponential Circle of law firms who have reached ‘escape velocity’ and left the rest behind.

Continue Reading