The sensor sends out electromagnetic waves in a broad beam, which are intercepted and reflected back by objects (or people) in their path.

Category: electronics – Page 53

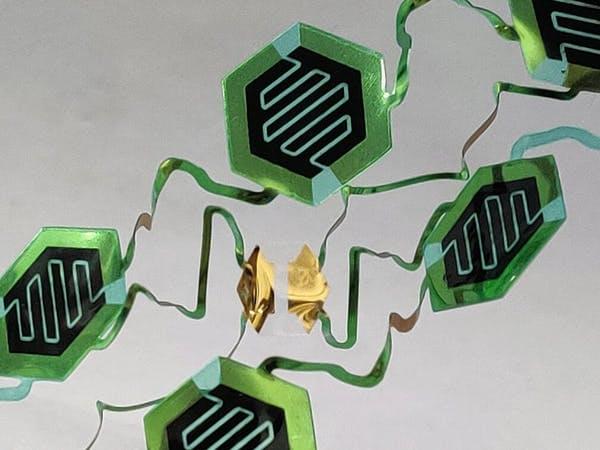

Google may be developing wearables that respond to skin gestures

Google has patented technology that will let users control its smartwatches and earbuds by simply touching their skin.

The patent titled “Skin interface for Wearables: Sensor fusion to improve signal quality” was spotted by folks over at LetsGoDigital. It details tech that users can use to operate wearable devices using skin gestures.

Patent documents show that users can swipe or tap the skin near the wearables in order to control them. The gesture creates a mechanical wave that is picked up by the sensors in the wearables. The “Sensor Fusion” tech then combines this movement data collected from various sensors into an input command for the wearable.

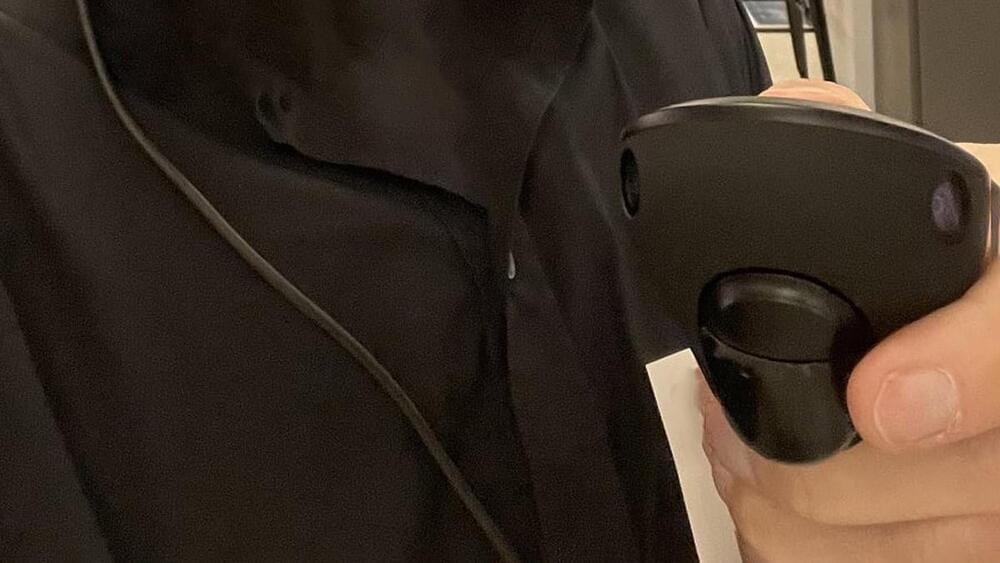

Magic Leap 2 Controller May Use On-board Inside-out Tracking, an Industry-first

A new photo of Magic Leap 2 appears to show the device’s controller equipped with cameras for inside-out tracking which would be the first time we’ve seen the approach employed in a commercial XR headset.

Though we learned plenty of interesting details about the forthcoming Magic Leap 2 AR headset back in January, it looks like there’s still some secrets left to uncover.

A recent photo of Magic Leap 2 posted by Peter H. Diamandis is, as far as we know, the first time we’ve gotten a clear look at the front of the Magic Leap 2 controller. The photo clearly shows what appear to be two camera sensors on the controller, indicating a high likelihood it will have on-board inside-out tracking.

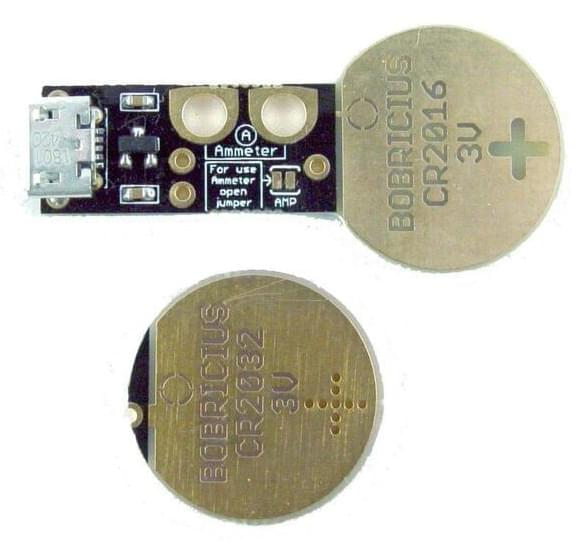

Coin Cell Eliminator Does More Than Save Batteries

Coin cells are useful things that allow us to run small electronic devices off a tiny power source. However, they don’t have a lot of capacity, and they can run out pretty quickly if you’re hitting them hard when developing a project. Thankfully, [bobricius] has just the tool to help.

The device is simple – it’s a PCB sized just so to fit into a slot for a CR2016 or CR2032 coin cell. The standard board fits a CR2016 slot thanks to the thickness of the PCB, and a shim PCB can be used to allow the device to be used in a CR2032-sized slot instead.

It’s powered via a Micro USB connector, and has a small regulator on board to step down the 5 V supply to the requisite 3 V expected from a typical coin cell. [bobricius] also gave the device a neat additional feature – a pair of pads for easy attachment of multimeter current probes. Simply open the jumper on the board, hook up a pair of leads, and it’s easy to measure the current being drawn from the ersatz coin cell.

DIY Hydrophone Listens In On The Deep For Cheap

The microphone is a pretty ubiquitous piece of technology that we’re all familiar with, but what if you’re not looking to record audio in the air, and instead want to listen in on what’s happening underwater? That’s a job for a hydrophone! Unfortunately, hydrophones aren’t exactly the kind of thing you’re likely to find at the big-box electronics store. Luckily for us, [Jules Ryckebusch] picked up a few tricks in his 20-year career as a Navy submariner, and has documented his process for building a sensitive hydrophone without needing a military budget.

Fascinated by all the incredible sounds he used to hear hanging around the Sonar Shack, [Jules] pored over documents related to hydrophone design from the Navy and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) until he distilled it all down to a surprisingly straightforward build. The key to the whole build is a commercially available cylindrical piezoelectric transducer designed for underwater communication that, incredibly, costs less than $20 USD a pop.

The transducer is connected to an op-amp board of his own design, which has been adapted from his previous work with condenser microphones. [Jules] designed the 29 × 26 mm board to fit neatly within the diameter of the transducer itself. The entire mic and preamp assembly can be cast inside a cylinder of resin. Specifically, he’s found an affordable two-part resin from Smooth-On that has nearly the same specific gravity as seawater. This allows him to encapsulate all the electronics in a way that’s both impervious to water and almost acoustically transparent. A couple of 3D-printed molds later, the hydrophone was ready to cast.

Joby under NTSB scanner after air taxi prototype crashes in California

The US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) says it is investigating the February 16 crash of a Joby Aviation air taxi prototype in Jolon, California.

The experimental air taxi was being piloted remotely when it went down during a flight at the company’s test base on Wednesday. According to a preliminary report by the FAA, no injuries have been reported.