“I view string theory as the most promising way to quantize matter and gravity in a unified way. We need both quantum gravity and we need unification and a quantization of gravity. One of the reasons why string theory is promising is that there are no singularities associated with those singularities are the same type that they offer point particles.” — Robert Brandenberger.

In this thought-provoking conversation, my grad school mentor, Robert Brandenberger shares his unique perspective on various cosmological concepts. He challenges the notion of the fundamental nature of the Planck length, questioning its significance and delving into intriguing debates surrounding its importance in our understanding of the universe. He also addresses some eyebrow-raising claims made by Elon Musk about the limitations imposed by the Planck scale on the number of digits of pi.

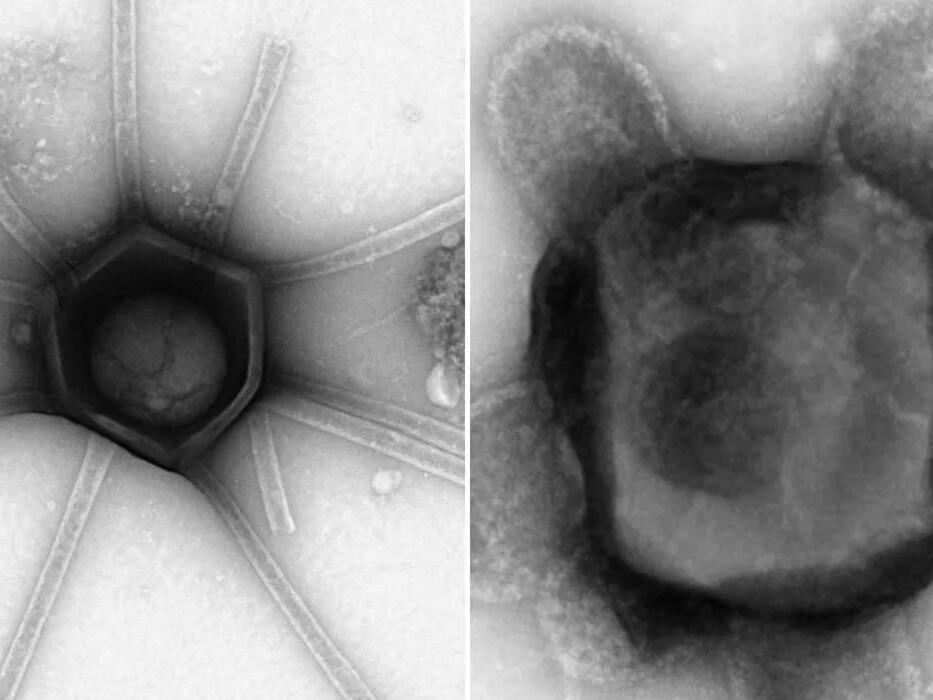

Moving on to the topic of inflation and its potential detectability, Robert sheds light on the elusive B mode fluctuations and the role they play in understanding the flaws of general relativity. He explains why detecting these perturbations at the required scale may be beyond our current technological capabilities. The discussion further explores the motivations behind the search for cosmic strings in the microwave sky and the implications they hold for particle physics models beyond the standard model.

With his expertise in gravity and the quantization of mass, Robert Brandenberger emphasizes the need for a quantum mechanical approach to gravity. He discusses the emergence of time, space, and a metric from matrix models, offering new insights into the foundations of our understanding of the universe. The speaker’s work challenges conventional notions of inflation and proposes alternative models, such as string gas cosmology, as potential solutions.