Simulations deliver hints on how the multiverse produced according to the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics might be compatible with our stable, classical Universe.

Visit our website for up-to-the-minute updates:

www.royaltyside.blogspot.com.

Follow us.

Facebook: www.facebook.com/royaltysides.

Twitter: www.x.com/RoyaltySide.

Instagram : www.instagram.com/royaltysideofficial/

#royaltyside #NASA #Astronomy#HiggsBoson #GodParticle #ParticlePhysics #LargeHadronCollider #HiggsField #PhysicsBreakthrough #ScienceNews #StandardModel #MaxPlanckInstitute #LHC #CERN #PhysicsDiscovery #ScienceExplained #HL-LHC #HiggsMechanism #DarkMatter #DarkEnergy #Cosmology #QuantumPhysics #NewPhysics #Wboson #Zboson #Quarks #ScientificBreakthrough #HiggsDecay #CharmQuarks #ParticleInteraction #HiggsResearch #BeyondPhysics #PhysicsRevolution #ScientificDiscovery

This idea stems from General Relativity, which shows that space and time are not fixed but dynamic and interwoven. Two key discoveries in the early 20th century solidified this understanding. First, Vesto Slipher observed that light from many nebulae was redshifted, indicating they were moving away. Second, Edwin Hubble measured distances to these galaxies and found that the farther they were, the faster they receded. This correlation, now known as Hubble’s Law, confirmed that the Universe is expanding.

Scientists often use analogies to explain this phenomenon. The “balloon analogy” imagines galaxies as coins on a balloon’s surface, moving apart as the balloon inflates. Another analogy is a loaf of raisin bread dough, where the raisins (galaxies) move apart as the dough (space) expands. However, these analogies fall short in some respects. Unlike the dough or balloon, the Universe doesn’t expand into anything; it’s all there is.

Observations suggest the observable Universe is only a fraction of a potentially infinite cosmos. While light from unseen regions will eventually reach us, expanding spacetime itself ensures galaxies continue moving farther apart. The theory of cosmic inflation suggests that our Universe is one “bubble” in a vast multiverse, though these regions remain isolated from one another.

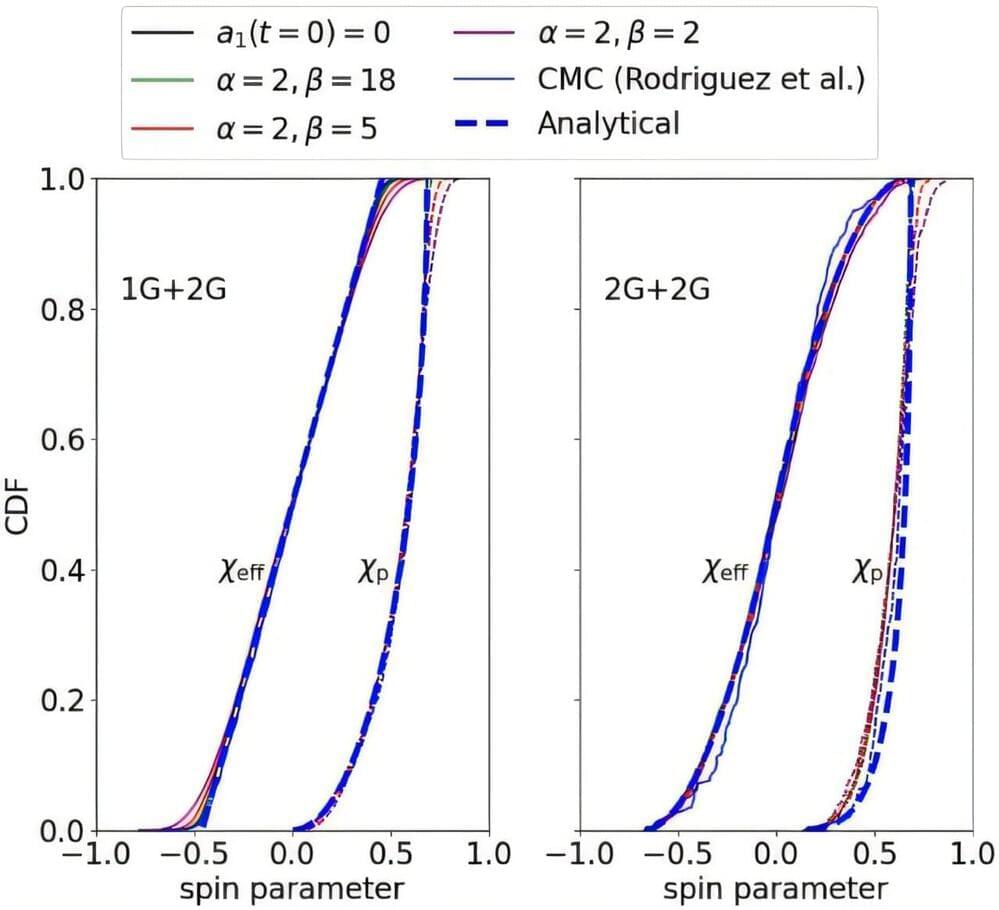

The size and spin of black holes can reveal important information about how and where they formed, according to new research.

The study, led by scientists at Cardiff University, tests the idea that many of the black holes observed by astronomers have merged multiple times within densely populated environments containing millions of stars.

The work is published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Observations with the South Pole Telescope have revealed an independent addition to the biggest problem in cosmology.

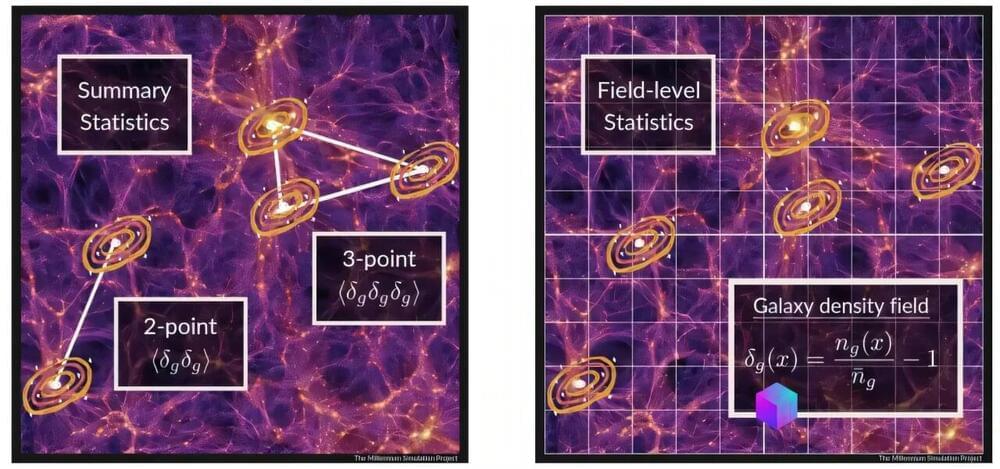

Galaxies are not islands in the cosmos. While globally the universe expands—driven by the mysterious “dark energy”—locally, galaxies cluster through gravitational interactions, forming the cosmic web held together by dark matter’s gravity. For cosmologists, galaxies are test particles to study gravity, dark matter and dark energy.

For the first time, MPA researchers and alumni have now used a novel method that fully exploits all information in galaxy maps and applied it to simulated but realistic datasets. Their study demonstrates that this new method will provide a much more stringent test of the cosmological standard model, and has the potential to shed new light on gravity and the dark universe.

From tiny fluctuations in the primordial universe, the vast cosmic web emerged: galaxies and galaxy clusters form at the peaks of (over)dense regions, connected by cosmic filaments with empty voids in between. Today, millions of galaxies sit across the cosmic web. Large galaxy surveys map those galaxies to trace the underlying spatial matter distribution and track their growth or temporal evolution.

Focused on the Antlia Cluster — a dense assembly of galaxies within the Hydra–Centaurus Supercluster located around 130 million light-years from Earth — the image captures only a small portion of the 230 galaxies that make up the cluster, revealing a diverse array of galaxy types within as well as thousands of background galaxies beyond.

The Dark Energy Camera (DECam) was originally built for the Dark Energy Survey (DES), an international collaboration that began in 2013 and concluded its observations in 2019. Over the course of the survey, scientists mapped hundreds of millions of galaxies in an effort to understand the nature of dark energy — a mysterious force thought to drive the accelerated expansion of our universe. The universe’s acceleration challenges predictions made by Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity, making dark energy one of the most perplexing mysteries in modern cosmology. Dark matter, meanwhile, refers to the mysterious and invisible substance that seems to hold galaxies together. This is another major conundrum scientists are still trying to fully penetrate.

Observations made of galaxy clusters have already helped scientists unravel some of the processes driving galaxy evolution as they search for clues about the history of our universe. In this sense, galaxy clusters act as “cosmic laboratories” where gravitational influence driven by dark matter and cosmic expansion driven by dark energy can be studied on incredibly large scales.

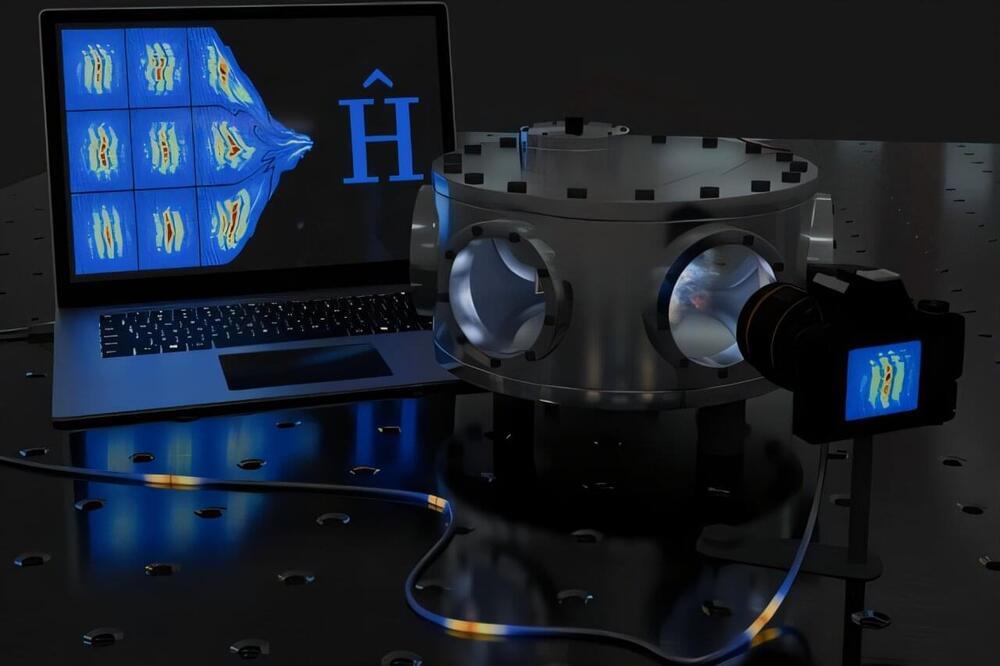

Quantum physics is a very diverse field: it describes particle collisions shortly after the Big Bang as well as electrons in solid materials or atoms far out in space. But not all quantum objects are equally easy to study. For some—such as the early universe—direct experiments are not possible at all.

However, in many cases, quantum simulators can be used instead: one quantum system (for example, a cloud of ultracold atoms) is studied in order to learn something about another system that looks physically very different, but still follows the same laws, i.e. adheres to the same mathematical equations.

It is often difficult to find out which equations determine a particular quantum system. Normally, one first has to make theoretical assumptions and then conduct experiments to check whether these assumptions prove correct.

Physicists have proposed a solution to a long-standing puzzle surrounding the GD-1 stellar stream, one of the most well-studied streams within the galactic halo of the Milky Way, known for its long, thin structure, and unusual spur and gap features.

The team of researchers, led by Hai-Bo Yu at the University of California, Riverside, proposed that a core-collapsing self-interacting dark matter (SIDM) “subhalo” — a smaller, satellite halo within the galactic halo — is responsible for the peculiar spur and gap features observed in the GD-1 stellar stream.

Study results appear in The Astrophysical Journal Letters in a paper titled “The GD-1 Stellar Stream Perturber as a Core-collapsed Self-interacting Dark Matter Halo.” The research could have significant implications for understanding the properties of dark matter in the universe.