Instead of the big bang, some physicists have suggested that our universe may have come from a big bounce following another universe contracting – but quantum theory could rule this out

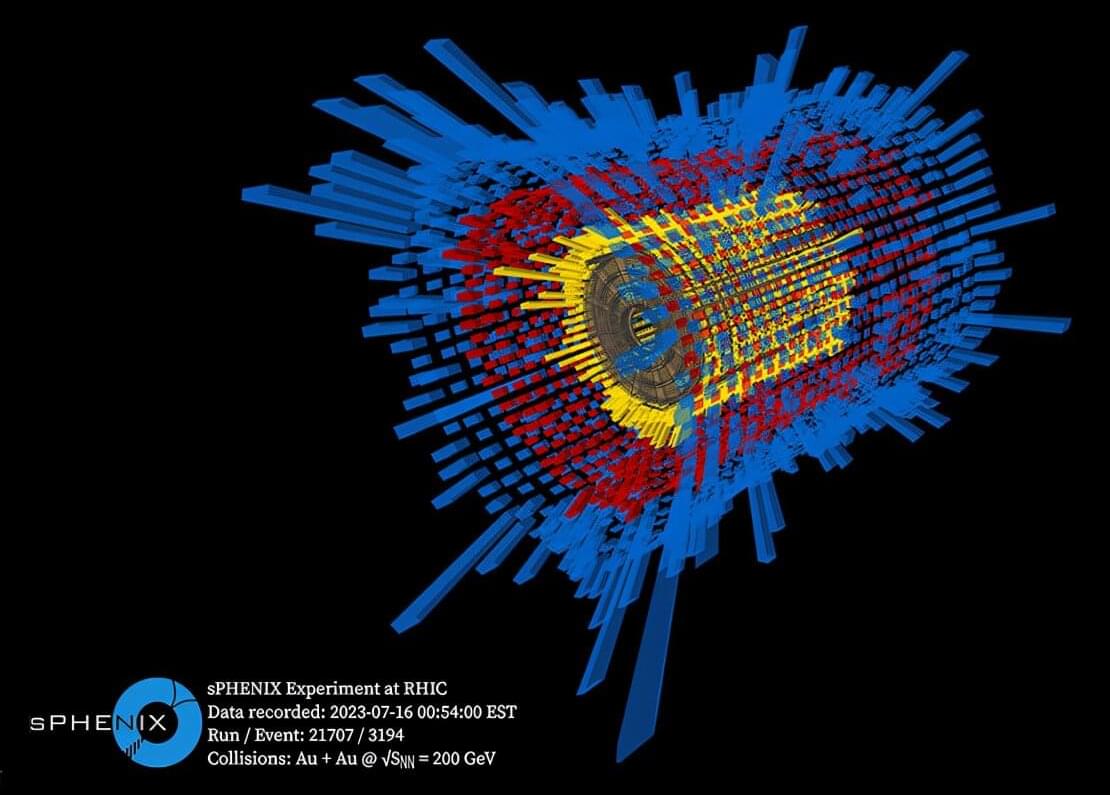

The sPHENIX particle detector, the newest experiment at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory, has released its first physics results: precision measurements of the number and energy density of thousands of particles streaming from collisions of near-light-speed gold ions.

As described in two papers recently accepted for publication in Physical Review C and the Journal of High Energy Physics, these measurements lay the foundation for the detector’s detailed exploration of the quark–gluon plasma (QGP), a unique state of matter that existed just microseconds after the Big Bang some 14 billion years ago. Both studies are available on the arXiv preprint server.

The new measurements reveal that the more head-on the nuclear smashups are, the more charged particles they produce and the more total energy those firework-like sprays of particles carry. That matches nicely with results from other detectors that have tracked QGP-generating collisions at RHIC since 2000, confirming that the new detector is performing as promised.

I have for a long time been searching for applications of the philosophy of Wittgenstein, particularly later Wittgenstein, to physics. I believe I have found that application in the work of Peter Putnam, who, building on the philosophy of Sir Arthur Eddington, Everett (of Many Worlds fame), and John Wheeler, constructed, in his private musings, the beginnings of a verbal, syntactical representation theory for quantum physics.

There have been a couple of articles lately about Putnam, starting with this one in Nautilus less than a month ago.

He was a relatively unknown figure who might have been as famous as Wittgenstein himself if not for a meddling mother.

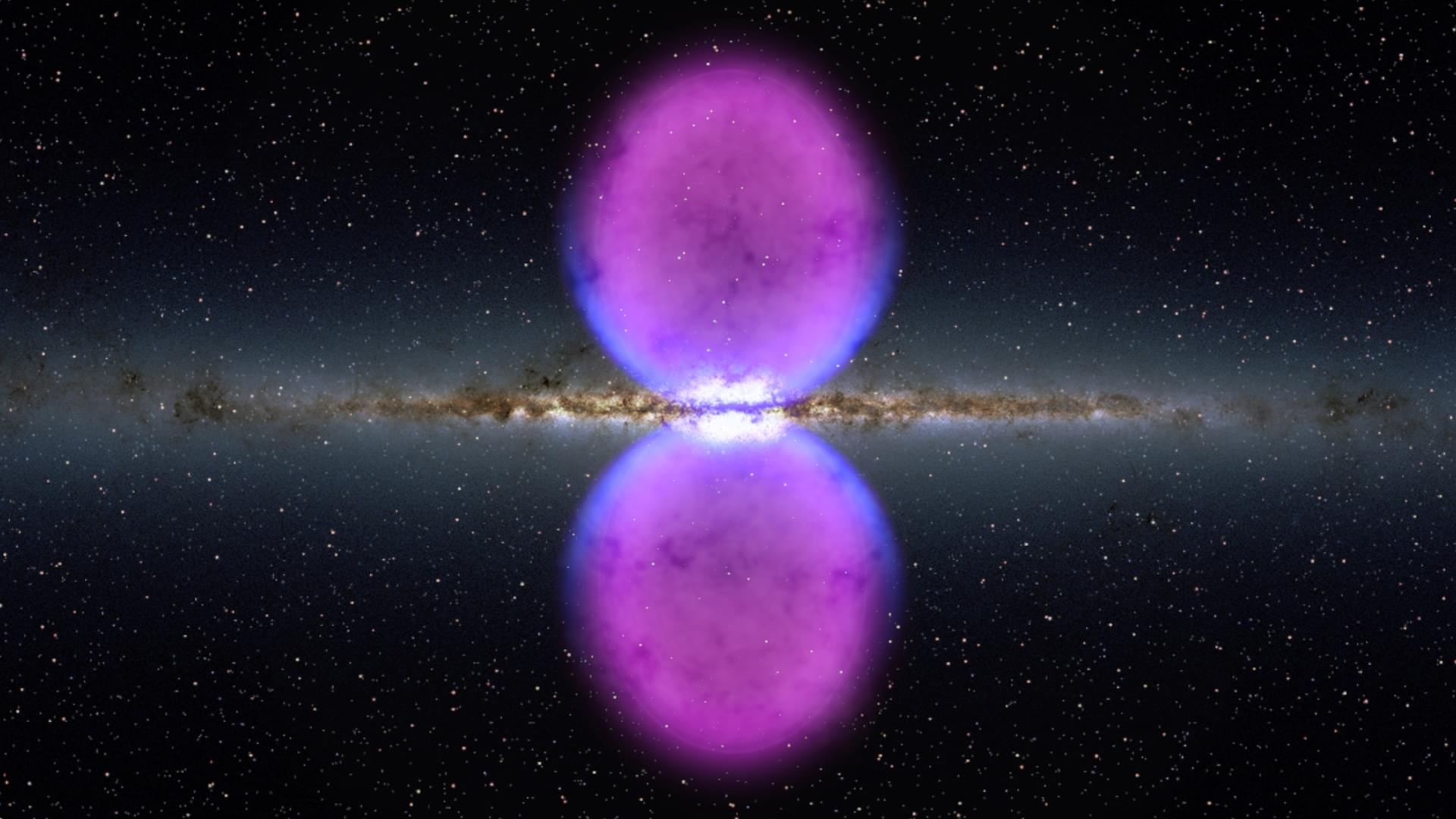

Instead of a tempest in a teapot, imagine the cosmos in a canister. Scientists have performed experiments using nested, spinning cylinders to confirm that an uneven wobble in a ring of electrically conductive fluid like liquid metal or plasma causes particles on the inside of the ring to drift inward. Since revolving rings of plasma also occur around stars and black holes, these new findings imply that the wobbles can cause matter in those rings to fall toward the central mass and form planets.

The scientists found that the wobble could grow in a new, unexpected way. Researchers already knew that wobbles could grow from the interaction between plasma and magnetic fields in a gravitational field. But these new results show that wobbles can more easily arise in a region between two jets of fluid with different velocities, an area known as a free shear layer.

“This finding shows that the wobble might occur more often throughout the universe than we expected, potentially being responsible for the formation of more solar systems than once thought,” said Yin Wang, a staff research physicist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) and lead author of the paper reporting the results in Physical Review Letters. “It’s an important insight into the formation of planets throughout the cosmos.”

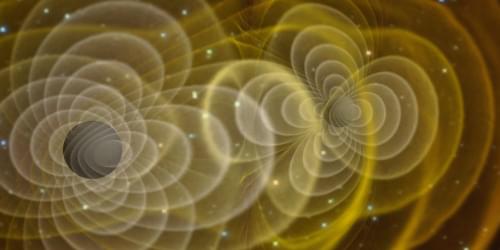

In addition to their high masses, the black holes are also rapidly spinning.

“This is the most massive black hole binary we’ve observed through gravitational waves, and it presents a real challenge to our understanding of black hole formation,” says Mark Hannam of Cardiff University and a member of the LVK Collaboration. “Black holes this massive are forbidden through standard stellar evolution models. One possibility is that the two black holes in this binary formed through earlier mergers of smaller black holes.”

The researchers behind these findings uncovered the Infinity Galaxy while examining images from the JWST’s 255-hour treasury COSMOS-Web survey. In addition to the suspected direct collapse black hole that sits between the colliding galaxies, the team found that each nucleus of those galaxies also contains a supermassive black hole!

“Everything is unusual about this galaxy. Not only does it look very strange, but it also has this supermassive black hole that’s pulling a lot of material in,” team leader and Yale University researcher Pieter van Dokkum said in a statement. “The biggest surprise of all was that the black hole was not located inside either of the two nuclei but in the middle.

We asked ourselves: How can we make sense of this?

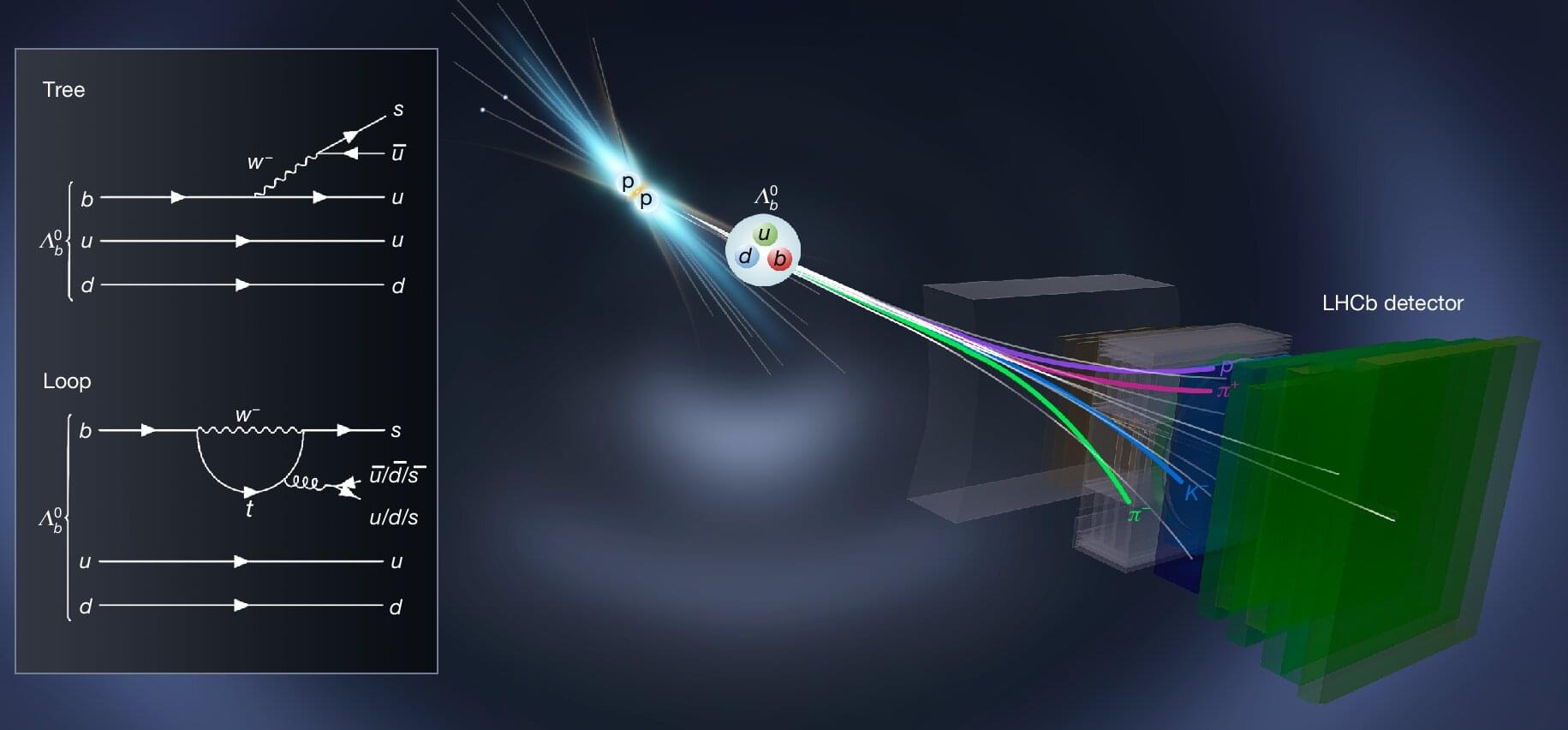

The first-known observations of matter–antimatter asymmetry in a decaying composite subatomic particle that belongs to the baryon class are reported from the LHCb experiment located at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN. This effect, known as charge–parity (CP) violation, has been theoretically predicted, but hitherto escaped observation in baryons. The experimental verification of this asymmetry violation in baryons, published in Nature this week, is important as baryons make up most of the matter in the observable universe.

Cosmological models suggest that matter and antimatter were created in equal amounts at the Big Bang, but in the present-day universe matter seems to dominate antimatter. This imbalance is thought to be driven by differences in the behavior of matter and antimatter: a violation of symmetry known as CP violation.

This effect has been predicted by the Standard Model of physics and observed experimentally in subatomic particles called mesons more than 60 years ago, but never previously observed in baryons. As opposed to mesons, which are formed by two quarks, baryons are formed by three quarks—particles that make up most of matter such as neutrons and protons are baryons.