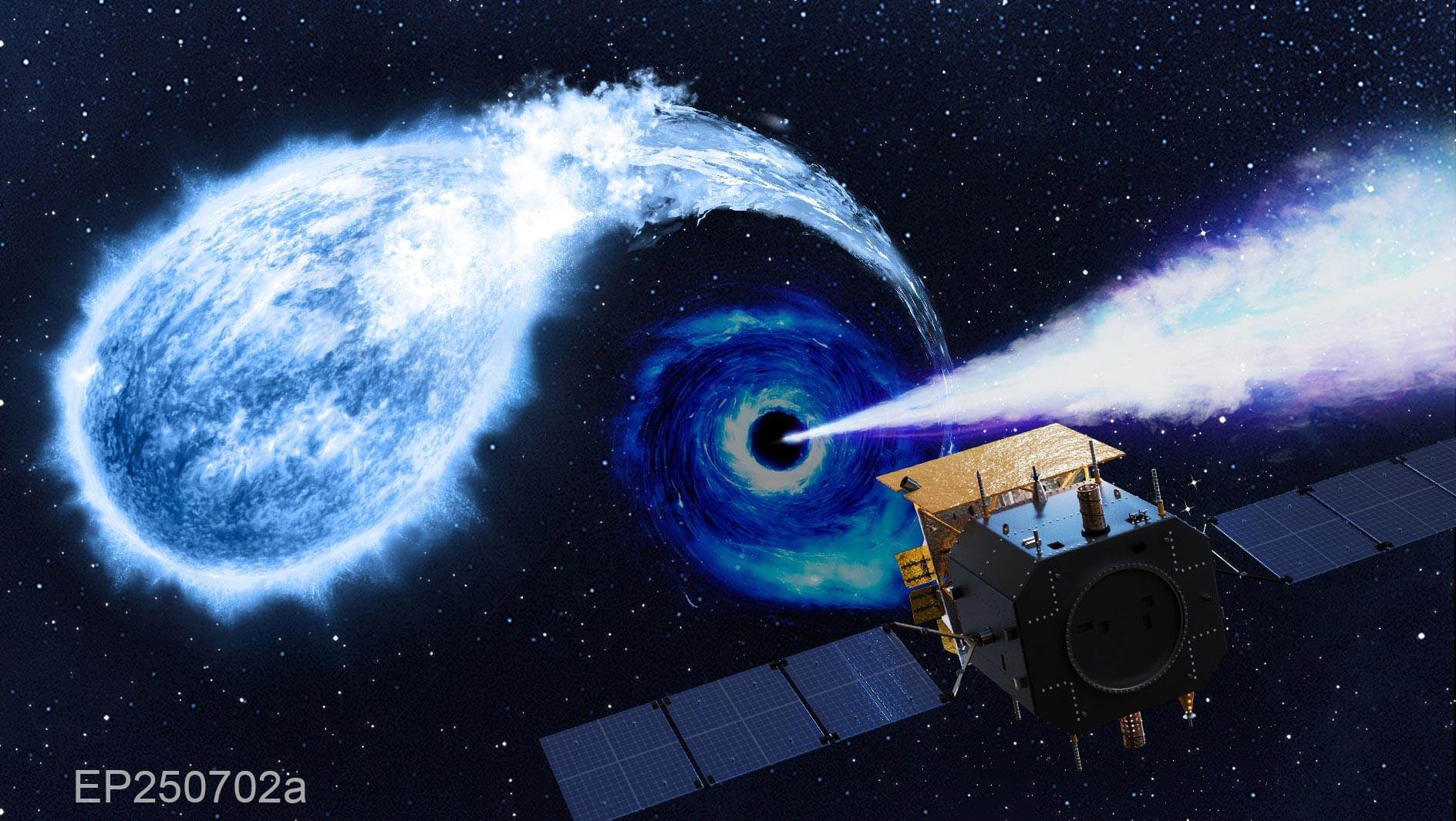

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope have confirmed the earliest supernova ever observed, linked to the gamma-ray burst GRB 250314A. The explosion occurred when the universe was just 730 million years old and looks surprisingly similar to modern supernovae, offering new insight into how the first massive stars lived and died.

Paperlink : https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.

Visit our website for up-to-the-minute updates:

www.nasaspacenews.com.

Follow us.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/nasaspacenews.

Twitter: https://twitter.com/SpacenewsNasa.

Join this channel to get access to these perks:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCEuhsgmcQRbtfiz8KMfYwIQ/join.

#NSN #NASA #Astronomy