A discrepancy between mathematics and physics has plagued astrophysicists’ understanding of how supermassive black holes merge, but dark matter may have the answer.

Category: cosmology – Page 113

HUXLEY: THE ORACLE Trailer (Official)

Official trailer for HUXLEY: THE ORACLE, the next prequel story in Ben Mauro’s post apocalyptic sci-fi universe! The Oracle Empire is at the height of its power, Max is a young recruit in the Ronin army sent out on an important mission deep into the wasteland with his team. What they discover could change the course of history forever. The AI wars have begun. Directed by Syama Pedersen of ‘ASTARTES’ Warhammer 40k and the renown UNIT IMAGE animation studio, dive deeper into the world of HUXLEY in this exciting new story.

If you would like to know more, read the original graphic novel and the new Oracle prequel book that tells the story glimpsed in the trailer. Available worldwide for pre-order from Thames \& Hudson. https://vol.co/collections/the-oracle.

Official site: https://www.huxleysaga.com

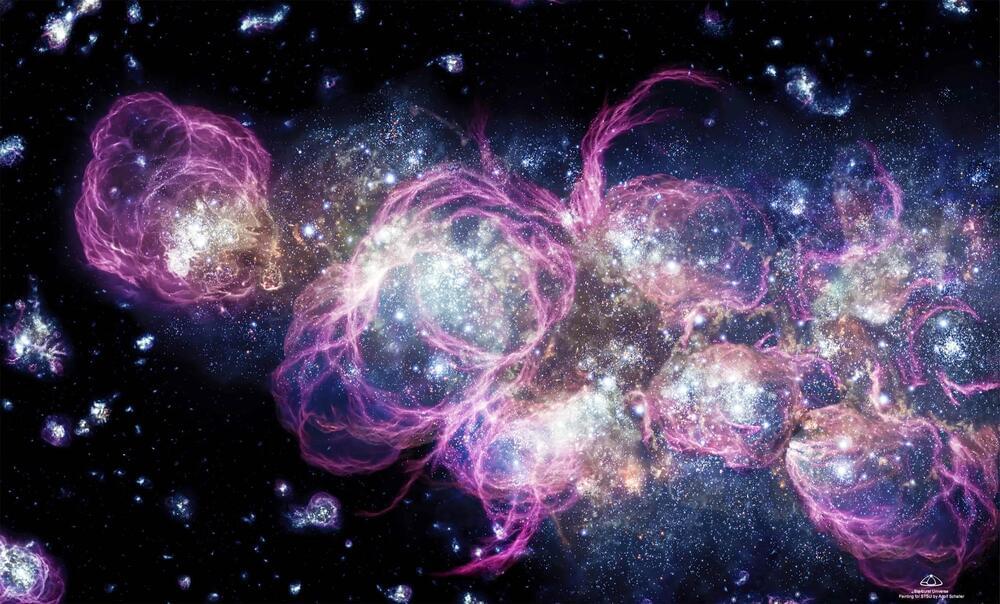

During the cosmic dawn, space wasn’t as empty as it seems today

Have you ever wondered what the universe looked like after the Big Bang when it was still in its infancy, a mere billion years old? With NASA’s new Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, we’re about to get a glimpse of the cosmic dawn.

This cosmic time machine is set to explore an era known as the cosmic dawn, a significant transition when the universe went from a foggy opacity to the stunning, star-filled expanse we observe today.

Behind this ambitious project is the esteemed astrophysicist Michelle Thaller from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

Cosmic Simulation Reveals How Black Holes Grow and Evolve

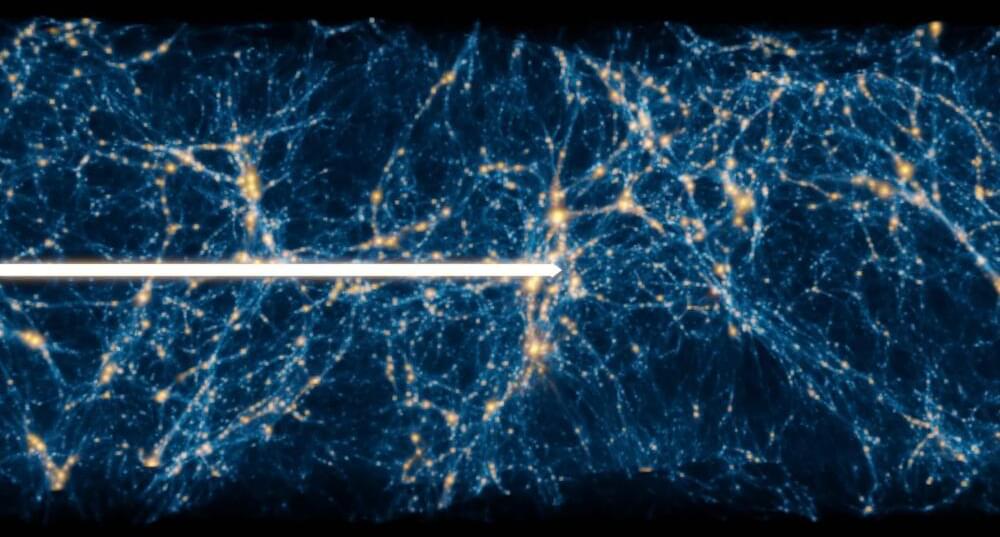

A team of astrophysicists led by Caltech has managed for the first time to simulate the journey of primordial gas dating from the early universe to the stage at which it becomes swept up in a disk of material fueling a single supermassive black hole. The new computer simulation upends ideas about such disks that astronomers have held since the 1970s and paves the way for new discoveries about how black holes and galaxies grow and evolve.

“Our new simulation marks the culmination of several years of work from two large collaborations started here at Caltech,” says Phil Hopkins, the Ira S. Bowen Professor of Theoretical Astrophysics.

The first collaboration, nicknamed has focused on the larger scales in the universe, studying questions such as how galaxies form and what happens when galaxies collide. The other, dubbed STARFORGE, was designed to examine much smaller scales, including how stars form in individual clouds of gas.

Dark matter seen separating from normal matter after galaxy cluster collision

Astronomers have uncovered the secrets behind an epic collision of two massive galaxy clusters, showing that dark matter and regular matter can actually separate during these huge events.

Located billions of light-years away, these clusters are home to thousands of galaxies and provide deep insights into the complexities of our universe.

When they collided, the dark matter — an invisible substance affected by gravity but not light — moved ahead of the normal matter, which includes gas and stars.

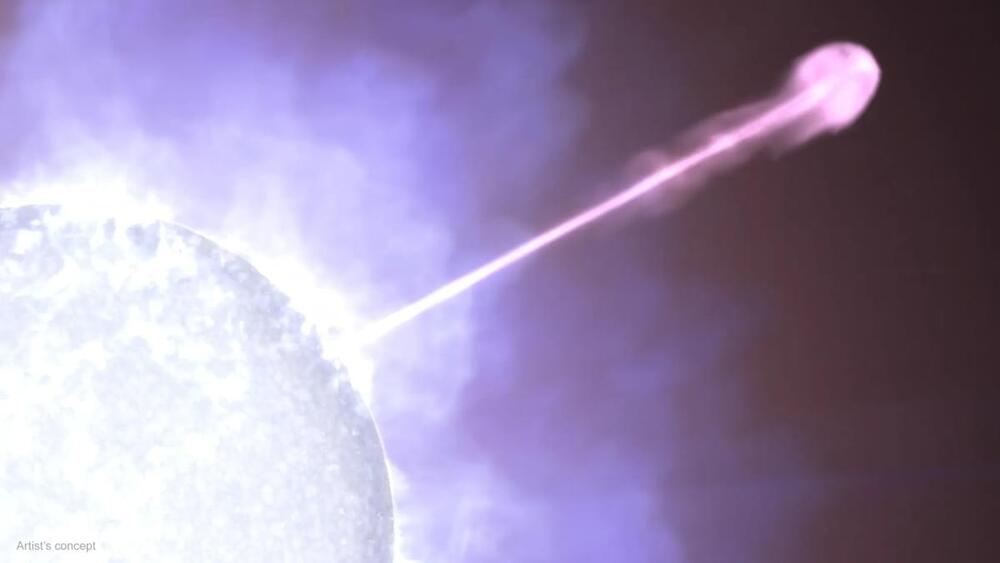

New feature spotted by Fermi Telescope in brightest gamma-ray burst of all time

NASA’s Fermi Telescope has revealed new details about the brightest of all time gamma-ray burst which may help explain these extreme and mysterious cosmic events.

Gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) usually last less than a second. They originate from the dense remains of a dead giant star’s core, called a neutron star. But what causes neutron stars to release huge amounts of energy in the form of gamma radiation is still a mystery.

In October 2022, astronomers detected the largest gamma-ray burst ever seen – GRB 221009A. It came from a supernova about 2.4 billion light years away. The event had an intensity at least 10 times greater than any other GRB detected. It was dubbed the BOAT, for brightest of all time.

Black Holes Can’t Be Created by Light

The formation of a black hole from light alone is permitted by general relativity, but a new study says quantum physics rules it out.

Black holes are known to form from large concentrations of mass, such as burned-out stars. But according to general relativity, they can also form from ultra-intense light. Theorists have speculated about this idea for decades. However, calculations by a team of researchers now suggest that light-induced black holes are not possible after all because quantum-mechanical effects cause too much leakage of energy for the collapse to proceed [1].

The extreme density of mass produced by a collapsed star can curve spacetime so severely that no light entering the region can escape. The formation of a black hole from light is possible according to general relativity because mass and energy are equivalent, so the energy in an electromagnetic field can also curve spacetime [2]. Putative electromagnetic black holes have become popularly known as kugelblitze, German for “ball lightning,” following the terminology used by Princeton University physicist John Wheeler in early studies of electromagnetically generated gravitational fields in the 1950s [3].

Does Dark Matter Really Exist?

An exploration of the question of whether dark matter exists and what the evidence for it is. My Patreon Page: https://www.patreon.com/johnmichaelgodierMy Eve…

Did abstract mathematics exist before the big bang?

Did abstract mathematics, such as Pythagoras’s theorem, exist before the big bang?

Simon McLeish Lechlade, Gloucestershire, UK

The notion of the existence of mathematical ideas is a complex one.

One way to look at it is that mathematics is about the use of logical thought to derive information, often information about other mathematical ideas. The use of objective logic should mean that mathematical ideas are eternal: they have always been, and always will be.