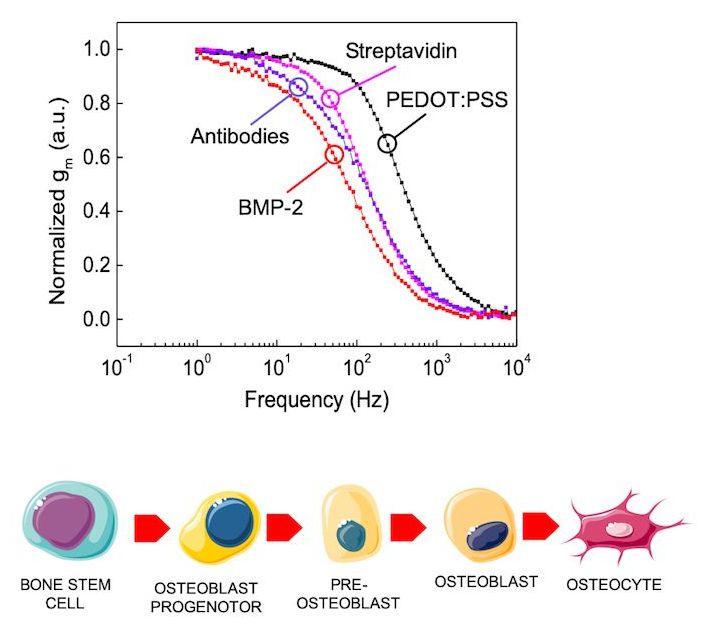

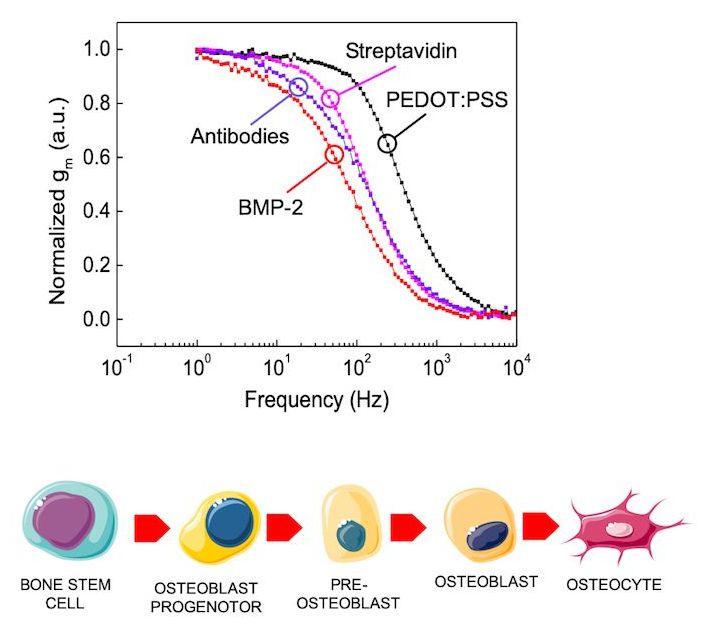

New technique detects real-time concentrations of an important cytokine molecule secreted as stem cells transform into bone.

Happy New Years!

Here is a little nostalgia and irony all rolled into one. Enjoy.

As 2019 winds to a close, the journey towards fully realised quantum computing continues: physicists have been able to demonstrate quantum teleportation between two computer chips for the first time.

Put simply, this breakthrough means that information was passed between the chips not by physical electronic connections, but through quantum entanglement – by linking two particles across a gap using the principles of quantum physics.

We don’t yet understand everything about quantum entanglement (it’s the same phenomenon Albert Einstein famously called “spooky action”), but being able to use it to send information between computer chips is significant, even if so far we’re confined to a tightly controlled lab environment.

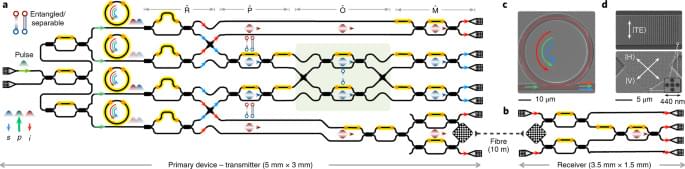

Integrated optics provides a versatile platform for quantum information processing and transceiving with photons1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. The implementation of quantum protocols requires the capability to generate multiple high-quality single photons and process photons with multiple high-fidelity operators9,10,11. However, previous experimental demonstrations were faced by major challenges in realizing sufficiently high-quality multi-photon sources and multi-qubit operators in a single integrated system4,5,6,7,8, and fully chip-based implementations of multi-qubit quantum tasks remain a significant challenge1,2,3. Here, we report the demonstration of chip-to-chip quantum teleportation and genuine multipartite entanglement, the core functionalities in quantum technologies, on silicon-photonic circuitry. Four single photons with high purity and indistinguishablity are produced in an array of microresonator sources, without requiring any spectral filtering. Up to four qubits are processed in a reprogrammable linear-optic quantum circuit that facilitates Bell projection and fusion operation. The generation, processing, transceiving and measurement of multi-photon multi-qubit states are all achieved in micrometre-scale silicon chips, fabricated by the complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor process. Our work lays the groundwork for large-scale integrated photonic quantum technologies for communications and computations.

It seemed as if AWS was lagging behind Google, Microsoft, and IBM when it comes to quantum computing but they’ve finally taken a step forward with their latest announcement.

AWS has officially announced the preview launch of its first-ever quantum computing service known as Braket. However, AWS is still not building their own quantum computer. Instead, they chose to partner with IonQ, Rigetti, and D-Wave in providing computing services through the cloud.

At Roswell we have developed the first Molecular Electronics chip. We utilized advances in semiconductor technology, nano-fabrication and bio-sensors to create standard CMOS chips that directly integrate sensor molecules into the CMOS integrated circuits.

Going “on-chip” to deploy bio-sensors provides unprecedented economics, precision, portability, and scalability. Our first chip is designed to read DNA; future chips will be designed for protein detection and other diverse bio-sensing applications.

For a time 20 years ago, millions of people, including corporate chiefs and government leaders, feared that the internet was going to crash and shatter on New Year’s Eve and bring much of civilization crumbling down with it. This was all because computers around the world weren’t equipped to deal with the fact of the year 2000. Their software thought of years as two digits. When the year 99 gave way to the year 00, data would behave as if it were about the year 1900, a century before, and system upon system in an almost infinite chain of dominoes would fail. Billions were spent trying to prepare for what seemed almost inevitable.

Twenty years ago, the world feared that a technological doomsday was nigh. It wasn’t, but Y2K had a lot of prescient things to say about how we interact with tech.

For the first time, researchers and scientists from the University of Bristol, in collaboration with the Technical University of Denmark (DTU), have achieved quantum teleportation between two computer chips. The team successfully developed chip-scale devices that are able to harness the applications of quantum physics by generating and manipulating single particles of light within programmable nano-scale circuits.

Unlike regular or science fiction teleportation which transfer particles from one place to another, with quantum teleportation, nothing physical is being transported. Rather, the information necessary to prepare a target system in the same quantum state as the source system is transmitted from one location to another, with the help of classical communication and previously shared quantum entanglement between the sending and receiving location.

In a feat that opens the door for quantum computers and quantum internet, the team managed to send information from one chip to another instantly without them being physically or electronically connected. Their work, published in the journal Nature Physics, contains a range of other quantum demonstrations. This chip-to-chip quantum teleportation was made possible by a phenomenon called quantum entanglement. The entanglement happens between two photons (two light particles) with the interaction taking place for a brief moment and the two photons sharing physical states. Quantum entanglement phenomenon is so strange that physicist Albert Einstein famously described it as ‘spooky action at a distance’.

Scientists at the University of Bristol and the Technical University of Denmark have achieved quantum teleportation between two computer chips for the first time. The team managed to send information from one chip to another instantly without them being physically or electronically connected, in a feat that opens the door for quantum computers and quantum internet.

This kind of teleportation is made possible by a phenomenon called quantum entanglement, where two particles become so entwined with each other that they can “communicate” over long distances. Changing the properties of one particle will cause the other to instantly change too, no matter how much space separates the two of them. In essence, information is being teleported between them.

Hypothetically, there’s no limit to the distance over which quantum teleportation can operate – and that raises some strange implications that puzzled even Einstein himself. Our current understanding of physics says that nothing can travel faster than the speed of light, and yet, with quantum teleportation, information appears to break that speed limit. Einstein dubbed it “spooky action at a distance.”

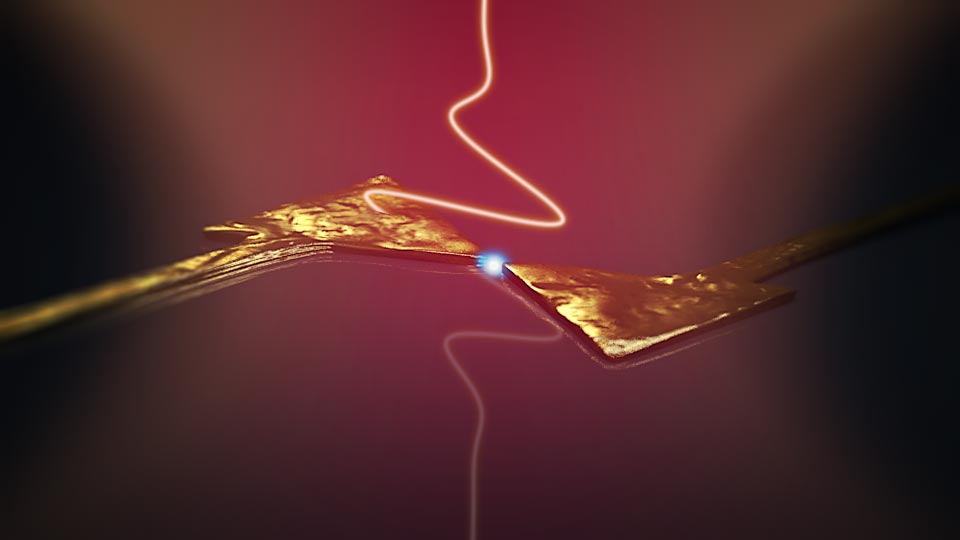

A European team of researchers including physicists from the University of Konstanz has found a way of transporting electrons at times below the femtosecond range by manipulating them with light. This could have major implications for the future of data processing and computing.

Contemporary electronic components, which are traditionally based on silicon semiconductor technology, can be switched on or off within picoseconds (i.e. 10-12 seconds). Standard mobile phones and computers work at maximum frequencies of several gigahertz (1 GHz = 109 Hz) while individual transistors can approach one terahertz (1 THz = 1012 Hz). Further increasing the speed at which electronic switching devices can be opened or closed using the standard technology has since proven a challenge. A recent series of experiments – conducted at the University of Konstanz and reported in a recent publication in Nature Physics – demonstrates that electrons can be induced to move at sub-femtosecond speeds, i.e. faster than 10-15 seconds, by manipulating them with tailored light waves.

“This may well be the distant future of electronics,” says Alfred Leitenstorfer, Professor of Ultrafast Phenomena and Photonics at the University of Konstanz (Germany) and co-author of the study. “Our experiments with single-cycle light pulses have taken us well into the attosecond range of electron transport”. Light oscillates at frequencies at least a thousand times higher than those achieved by purely electronic circuits: One femtosecond corresponds to 10-15 seconds, which is the millionth part of a billionth of a second. Leitenstorfer and his team from the Department of Physics and the Center for Applied Photonics (CAP) at the University of Konstanz believe that the future of electronics lies in integrated plasmonic and optoelectronic devices that operate in the single-electron regime at optical – rather than microwave – frequencies. “However, this is very basic research we are talking about here and may take decades to implement,” he cautions.