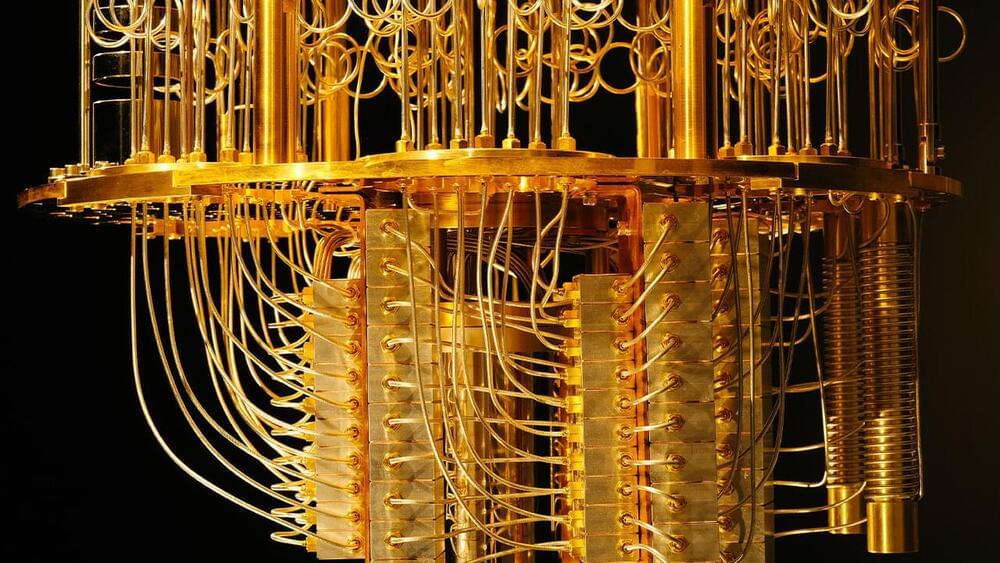

BERKELEY, Calif. 0, Jan. 20, 2022 — Atom Computing, the creators of the first quantum computer made of nuclear-spin qubits from optically-trapped neutral atoms, today announced closure of a $60M Series B round. Third Point Ventures led the round, followed by Primer Movers Lab and insiders including Innovation Endeavors, Venrock and Prelude Ventures. Following the completion of their first 100-qubit quantum computing system with world-record 40 second coherence times, Atom Computing will use this new investment to build their second-generation quantum computing systems and commercialize the technology.

“Atom Computing designed and built our first-generation machine, Phoenix 0, in less than two years and our team was the fastest to deliver a 100-qubit system,” said Rob Hays 0, CEO and President, Atom Computing. “We gained valuable learnings from the system and have proven the technology. The investment announced today accelerates the commercialization opportunities and we look forward to bringing this to market.”

With this new level of investment, the company will turn its focus to developing much larger systems that are required to run commercial use-cases with paradigm-shifting compute performance.