IBM has released two new complex quantum processors alongside a new framework that would allow us to track the first demonstration of quantum advantage.

In a major step toward practical quantum computers, Princeton engineers have built a superconducting qubit that lasts three times longer than today’s best versions.

“The real challenge, the thing that stops us from having useful quantum computers today, is that you build a qubit and the information just doesn’t last very long,” said Andrew Houck, Princeton’s dean of engineering and co-principal investigator. “This is the next big jump forward.”

In an article in the journal Nature, the Princeton team report that their new qubit lasts for over 1 millisecond. This is three times longer than the best ever reported in a lab setting, and nearly 15 times longer than the industry standard for large-scale processors.

Get a Wonderful Person Tee: https://teespring.com/stores/whatdamath.

More cool designs are on Amazon: https://amzn.to/3wDGy2i.

Alternatively, PayPal donations can be sent here: http://paypal.me/whatdamath.

Hello and welcome! My name is Anton and in this video, we will talk about an invention of a DNA bio computer.

Links:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06484-9

https://www.washington.edu/news/2016/04/07/uw-team-stores-di…perfectly/

Other videos:

https://youtu.be/x3jiY8rZAZs.

https://youtu.be/JGWbVENukKc.

#dna #biocomputer #genetics.

0:00 Quantum computer hype.

0:50 Biocomputers?

1:55 Original DNA computers from decades ago.

3:10 Problems with this idea.

3:50 New advances.

5:35 First breakthrough — DNA circuit.

7:30 Huge potential…maybe.

Support this channel on Patreon to help me make this a full time job:

https://www.patreon.com/whatdamath.

Bitcoin/Ethereum to spare? Donate them here to help this channel grow!

bc1qnkl3nk0zt7w0xzrgur9pnkcduj7a3xxllcn7d4

or ETH: 0x60f088B10b03115405d313f964BeA93eF0Bd3DbF

Space Engine is available for free here: http://spaceengine.org.

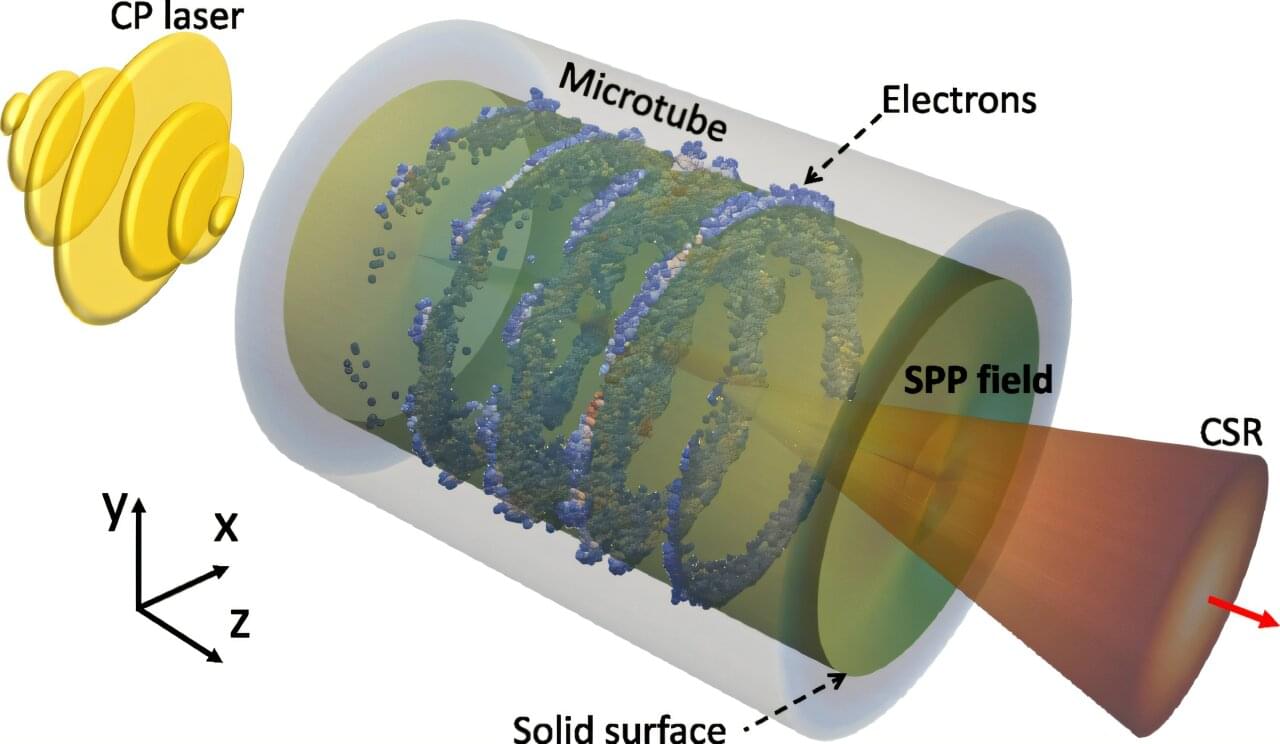

A particle accelerator that produces intense X-rays could be squeezed into a device that fits on a table, my colleagues and I have found in a new research project.

The way that intense X-rays are currently produced is through a facility called a synchrotron light source. These are used to study materials, drug molecules and biological tissues. Even the smallest existing synchrotrons, however, are about the size of a football stadium.

Our research, which is published in the journal Physical Review Letters, shows how tiny structures called carbon nanotubes and laser light could generate brilliant X-rays on a microchip. Although the device is still at the concept stage, the development has the potential to transform medicine, materials science and other disciplines.

Still, it’s not clear what type of qubit will win in the long run. Each type has design benefits that could ultimately make it easier to scale. Ions (which are used by the US-based startup IonQ as well as Quantinuum) offer an advantage because they produce relatively few errors, says Islam: “Even with fewer physical qubits, you can do more.” However, it’s easier to manufacture superconducting qubits. And qubits made of neutral atoms, such as the quantum computers built by the Boston-based startup QuEra, are “easier to trap” than ions, he says.

Besides increasing the number of qubits on its chip, another notable achievement for Quantinuum is that it demonstrated error correction “on the fly,” says David Hayes, the company’s director of computational theory and design, That’s a new capability for its machines. Nvidia GPUs were used to identify errors in the qubits in parallel. Hayes thinks that GPUs are more effective for error correction than chips known as FPGAs, also used in the industry.

Quantinuum has used its computers to investigate the basic physics of magnetism and superconductivity. Earlier this year, it reported simulating a magnet on H2, Helios’s predecessor, with the claim that it “rivals the best classical approaches in expanding our understanding of magnetism.” Along with announcing the introduction of Helios, the company has used the machine to simulate the behavior of electrons in a high-temperature superconductor.

Visionary, patient-centric health research for all — dr. julia moore vogel, phd — scripps research / long covid treatment trial.

Dr. Julia Moore Vogel, PhD, MBA is Assistant Professor and Senior Program Director at The Scripps Research Institute (https://www.scripps.edu/science-and-me… where she is responsible for managing a broad portfolio of patient-centric health research studies, including The Long COVID Treatment Trial (https://longcovid.scripps.edu/locitt-t/), a fully remote, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial targeting individuals with long COVID, testing whether the drug Tirzepatide can reduce or alleviate symptoms of long COVID.

Prior to this current role, Dr. Vogel managed The Participant Center (TPC) for the NIH All of Us Research Program (https://www.scripps.edu/science-and-me… which was charged with recruiting and retaining 350,000 individuals that represent the diversity of the United States. TPC aims to make it possible for interested individuals anywhere in the US to become active participants, for example by collaborating with numerous outreach partners to raise awareness, collecting biosamples nationwide, returning participants’ results and developing self-guided workflows that enable participants to join whenever is convenient for them.

Prior to joining the Scripps Research Translational Institute, Dr. Vogel created, proposed, fundraised for, and implemented research and clinical genomics initiatives at the New York Genome Center and The Rockefeller University. She oversaw the proposal and execution of grants, including a $44M NIH Center for Common Disease Genomics in collaboration with over 20 scientific contributors across seven institutions. She also managed corporate partnerships, including one with IBM that assessed the relative value of several genomic assays for cancer patients.

Dr. Vogel has a BS in Mathematics from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, a PhD in Computational Biology and Medicine from Cornell and an MBA from Cornell.

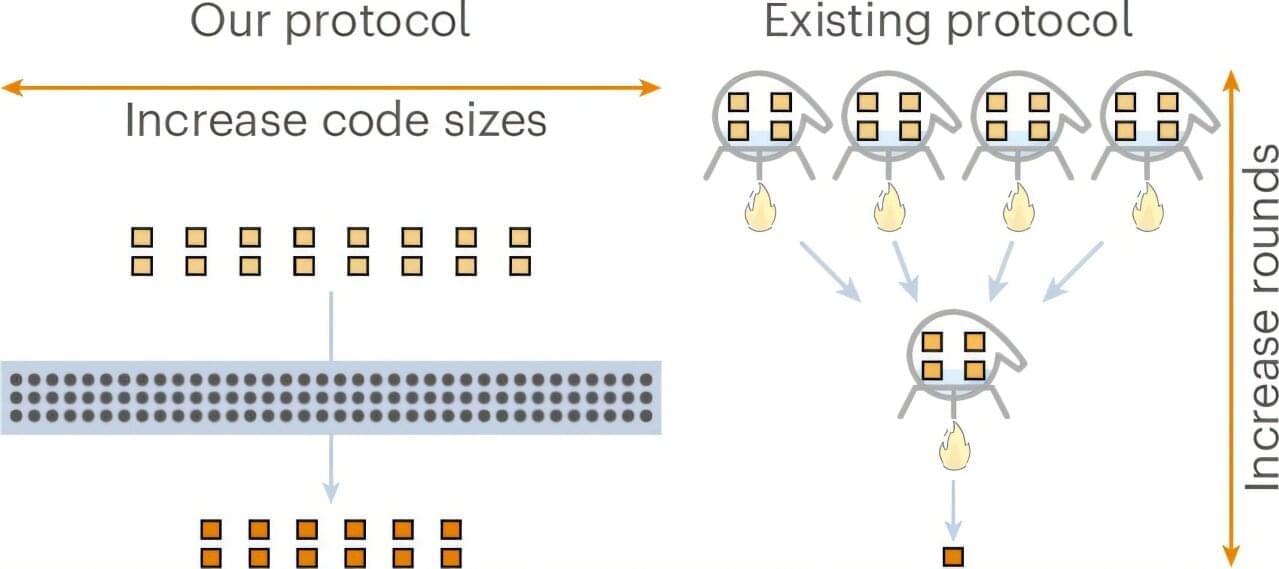

Researchers have demonstrated that the theoretically optimal scaling for magic state distillation—a critical bottleneck in fault-tolerant quantum computing—is achievable for qubits, improving on the previous best result by reaching a scaling exponent of exactly zero.

The work, published in Nature Physics, resolves a fundamental open problem that has persisted in the field for years.

“Broadly, I think that building quantum computers is a wonderful and inspiring goal,” Adam Wills, a Ph.D. student at MIT’s Center for Theoretical Physics and lead author of the study, told Phys.org.

Engineers have coaxed them into lasting longer, using a smarter materials stack and some painstaking fabrication.

Researchers in the United States say a superconducting qubit now holds its state for more than a millisecond, long enough to change how we think about useful quantum circuits. The result pushes lab records and nudges industrial roadmaps toward designs that look manufacturable rather than bespoke.