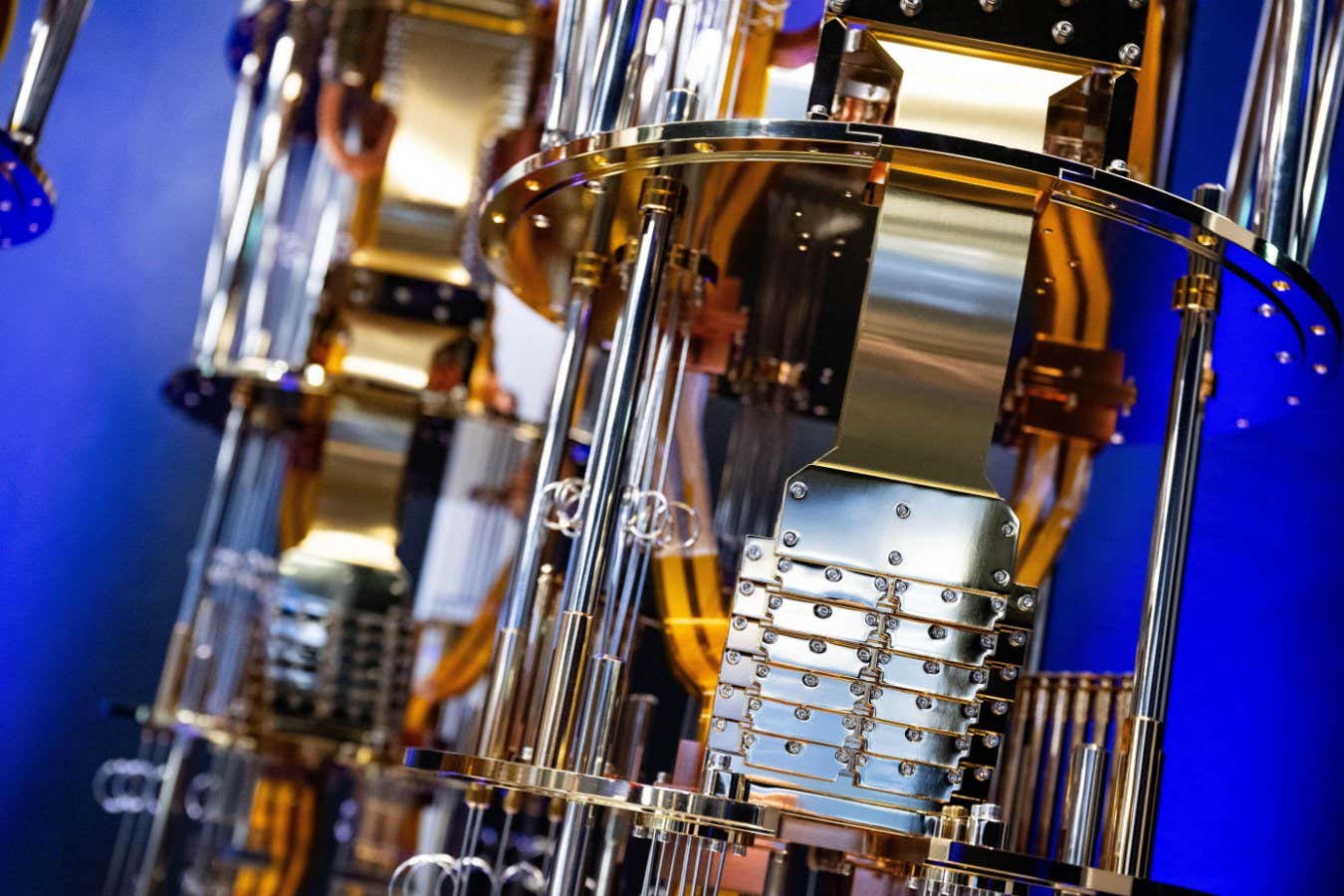

Quantum computers, systems that process information leveraging quantum mechanical effects, are expected to outperform classical computers on some complex tasks. Over the past few decades, many physicists and quantum engineers have tried to demonstrate the advantages of quantum systems over their classical counterparts on specific types of computations.

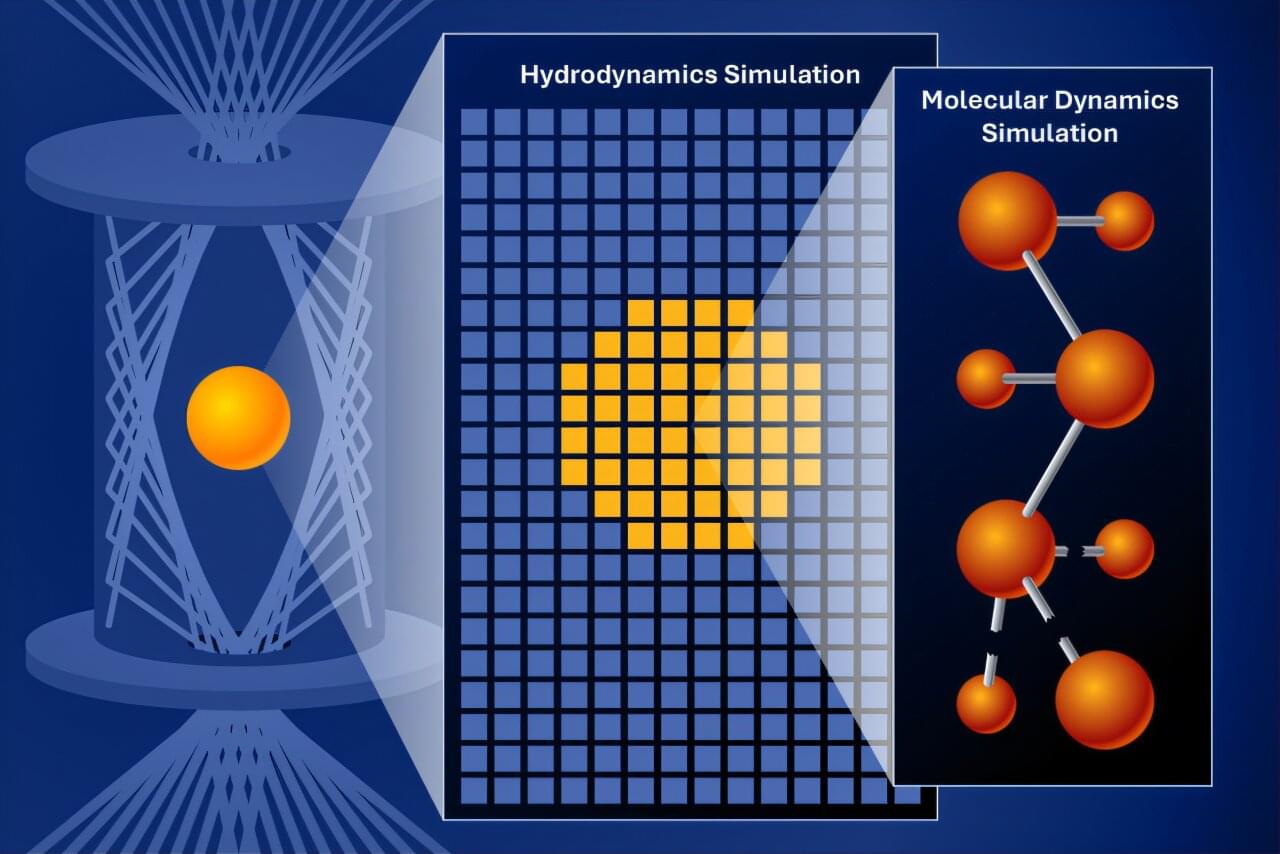

Researchers at Autonomous University of Barcelona and Hunter College of CUNY recently showed that quantum systems could tackle a problem that cannot be solved by classical systems, namely determining the even or odd nature of particle permutations without marking all and each one of the particles with a distinct label. This task essentially entails uncovering whether re-arranging particles from their original order to a new order requires an even or odd number of swaps in the position of particle pairs.

These researchers have been conducting research focusing on problems that entail the discrimination between quantum states for several years. Their recent paper, published in Physical Review Letters, demonstrates that quantum technologies could solve one of these problems in ways that are unfeasible for classical systems.