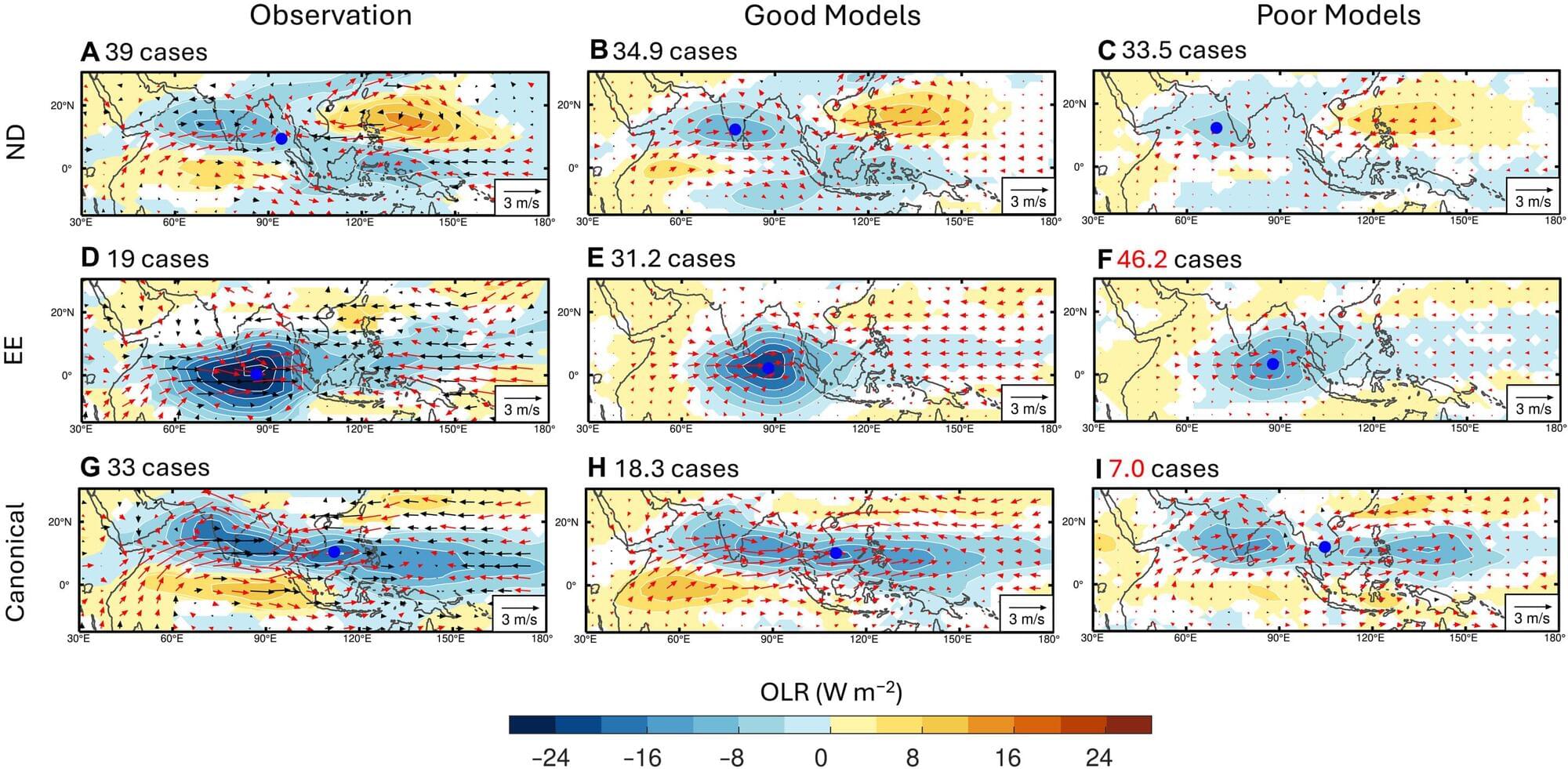

A climate study led by The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST), in collaboration with an international research team, reveals that under a high-emission scenario, the Northern Hemisphere summer monsoons region will undergo extreme weather events starting in 2064. Asia and broader tropical regions will face frequent “subseasonal whiplash” events, characterized by extreme downpours and dry spells alternating every 30 to 90 days which trigger climate disruptions with catastrophic impacts on food production, water management, and clean energy systems.

Published in Science Advances under the title “Increased Global Subseasonal Whiplash by Future BSISO Behavior,” the research was co-led by Prof. Lu Mengqian, Director of the Otto Poon Center for Climate Resilience and Sustainability and Associate Professor of the Department of Civil and Environmental at HKUST and Dr. Cheng Tat-Fan, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at HKUST, alongside collaborators from the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Sun Yat-Sen University and Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology.