Lightning strikes can more than double some mushroom crops, according to ongoing experiments that are jolting fungi with electricity.

Dear Colleagues.

ReWheel, Inc. was founded to save energy based on a simple truth that wasting energy is extremely not smart … as well as very damaging to our planet’s health.

Most of us are either scientists or believe in science. And that is how we know that we are losing the war against climate change. This war will not be won by any one technology but by our combined efforts. To protect our planet for our children and their children, and those who comes after, we need to act.

“Astronauts at the international space station expecting a delivery on Monday that private company SpaceX launched a cargo capsule loaded with supplies from Cape Canaveral early this morning the shipment. The company’s seventeenth to the orbiting outpost includes a new instrument to measure CO two in the atmosphere. Then peers Rebecca hersher reports it will be attached. To the space station measuring how much carbon dioxide is. In the atmosphere is really fundamental for understanding how the climate is changing. But it’s difficult for one thing. The amount of co two varies each day and each season and each year and measurements have to be both global and extremely precise. The new instrument can do both. It’s designed to scan the earth measuring not only how much co two is entering the atmosphere. But how much of the greenhouse gas is being absorbed by plants and oceans the instrument is called the orbiting carbon observatory three two other versions. Have previously been launched. Overall. NASA says the ability to measure co two from space has already helped scientists better understand our climate and predict how it will change”

KQED Radio

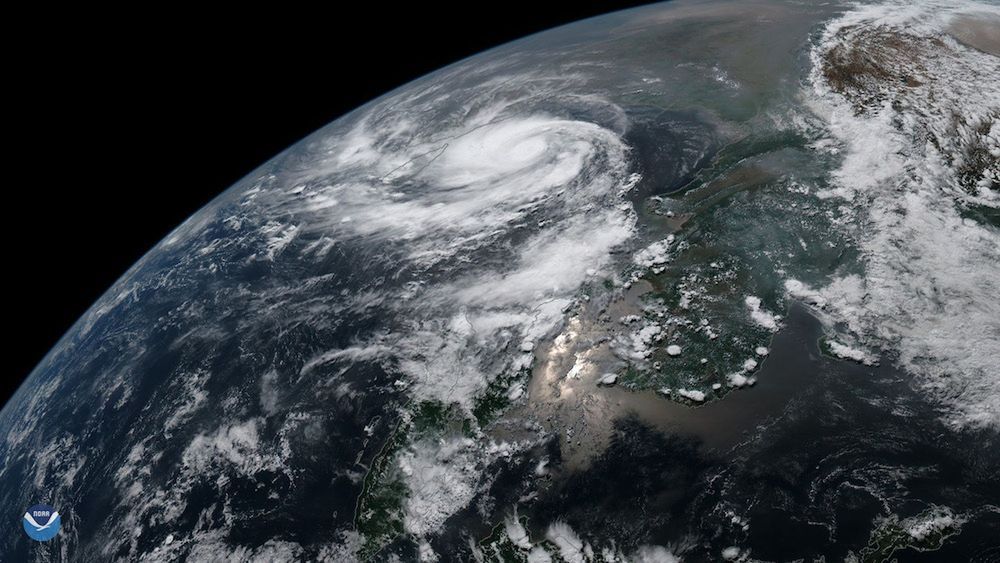

A massive cyclone is set to batter India over the next few days, spurring the biggest evacuation in the country’s history.

The extremely severe cyclone, dubbed “Fani,” is pummeling the Bay of Bengal and is projected to make landfall by Thursday night with approximately 120 mph (190 km/h) winds, with gusts up to 130 mph (210 km/h), according to the India Meteorological Department (IMD). Fani is also likely to bring “phenomenal” sea conditions in parts of the Bay of Bengal, according to the IMD.

More than 100 million people are in the path of the devastating cyclone, and nearly 900,000 people have been ordered to evacuate, the Associated Press reported. About 100,000 of those people are from the city of Puri, in the state of Odisha, which is home to the 858-year-old Jaganath Temple, the BBC reported. Officials fear that this ancient temple could be damaged by the cyclone.

There is enough room in the world’s existing parks, forests, and abandoned land to plant 1.2 trillion additional trees, which would have the CO2 storage capacity to cancel out a decade of carbon dioxide emissions, according to a new analysis by ecologist Thomas Crowther and colleagues at ETH Zurich, a Swiss university.

The research, presented at this year’s American Association for the Advancement of Science conference in Washington, D.C., argues that planting additional trees is one of the most effective ways to reduce greenhouse gases.

Trees are “our most powerful weapon in the fight against climate change,” Crowther told The Independent. Combining forest inventory data from 1.2 million locations around the world and satellite images, the scientists estimate there are 3 trillion trees on Earth — seven times more than previous estimates. But they also found that there is abundant space to restore millions of acres of additional forests, not counting urban and agricultural land.

The world’s oceans soak up about a quarter of the carbon dioxide that humans pump into the air each year—a powerful brake on the greenhouse effect. In addition to purely physical and chemical processes, a large part of this is taken up by photosynthetic plankton as they incorporate carbon into their bodies. When plankton die, they sink, taking the carbon with them. Some part of this organic rain will end up locked into the deep ocean, insulated from the atmosphere for centuries or more. But what the ocean takes, the ocean also gives back. Before many of the remains get very far, they are consumed by aerobic bacteria. And, just like us, those bacteria respire by taking in oxygen and expelling carbon dioxide. Much of that regenerated CO2 thus ends up back in the air.

A new study suggests that CO2 regeneration may become faster in many regions of the world as the oceans warm with changing climate. This, in turn, may reduce the deep oceans’ ability to keep carbon locked up. The study shows that in many cases, bacteria are consuming more plankton at shallower depths than previously believed, and that the conditions under which they do this will spread as water temperatures rise. The study was published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“The results are telling us that warming will cause faster recycling of carbon in many areas, and that means less carbon will reach the deep ocean and get stored there,” said study coauthor Robert Anderson, an oceanographer at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

Just as the modern computer transformed our relationship with bits and information, AI will redefine and revolutionize our relationship with molecules and materials. AI is currently being used to discover new materials for clean-tech innovations, such as solar panels, batteries, and devices that can now conduct artificial photosynthesis.

Today, it takes about 15 to 20 years to create a single new material, according to industry experts. But as AI design systems skyrocket in capacity, these will vastly accelerate the materials discovery process, allowing us to address pressing issues like climate change at record rates. Companies like Kebotix are already on their way to streamlining the creation of chemistries and materials at the click of a button.

Atomically precise manufacturing will enable us to produce the previously unimaginable.