In this cross-journal Collection, across Nature Communications, Communications Chemistry, Communications Materials and Scientific Reports, we focus on…

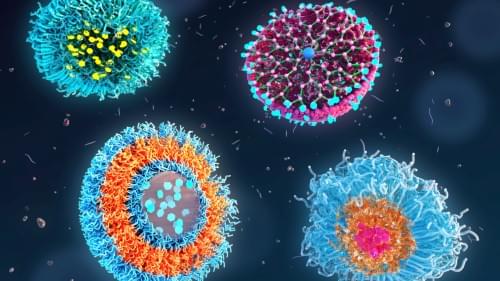

Most energy generators currently employed within the electronics industry are based on inorganic piezoelectric materials that are not bio-compatible and contribute to the pollution of the environment on Earth. In recent years, some electronics researchers and chemical engineers have thus been trying to develop alternative devices that can generate electricity for medical implants, wearable electronics, robots and other electronics harnessing organic materials that are safe, bio-compatible and non-toxic.

Researchers at the Materials Science Centre, Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur recently introduced a new device based on seeds from the mimosa pudica plant, which can serve both as a bio-piezoelectric nanogenerator and a self-chargeable supercapacitor. Their proposed device, outlined in a paper published in the Chemical Engineering Journal, was found to achieve remarkable efficiencies, while also having a lesser adverse impact on the environment.

“This study was motivated by the need for biocompatible, self-sustaining energy systems to power implantable medical devices (e.g., pacemakers, neurostimulators) and wearable electronics,” Prof. Dr. Bhanu Bhusan Khatua, senior author of the paper, told Tech Xplore.

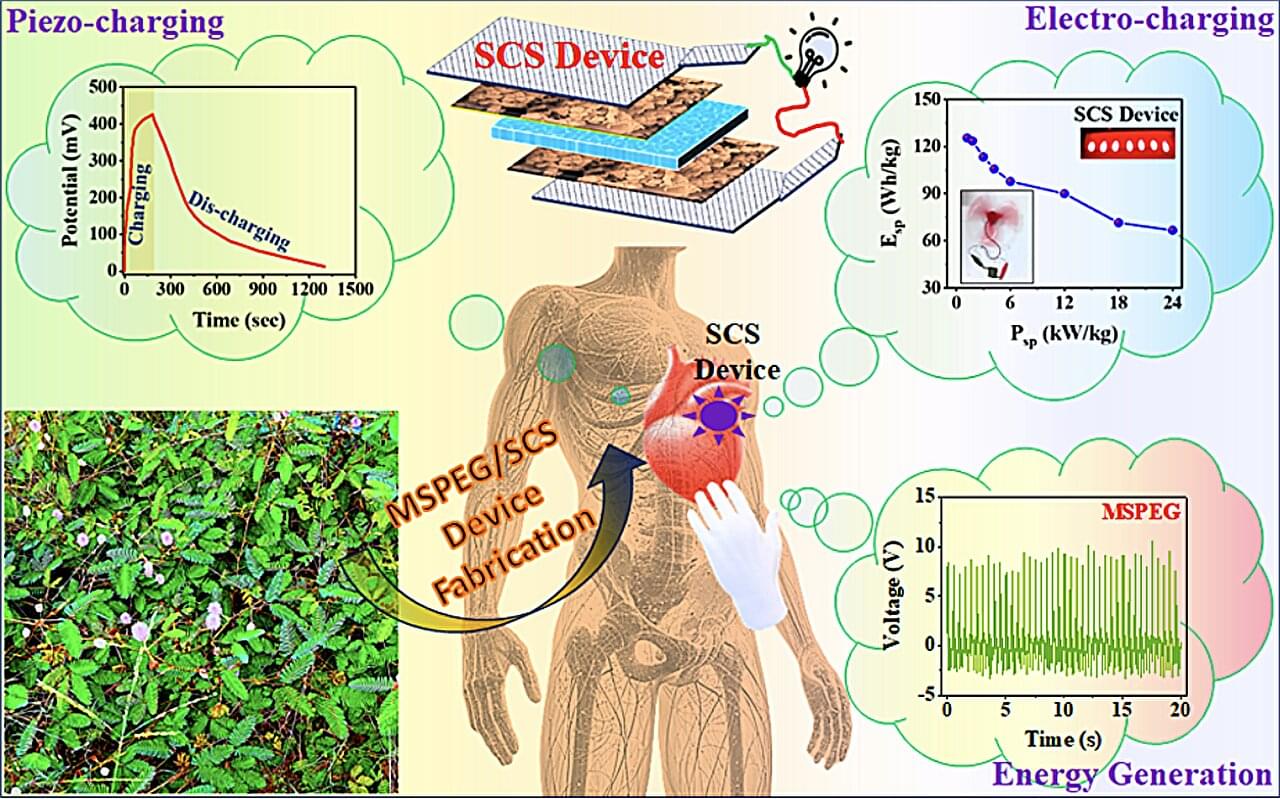

Proteins are the building blocks of life. They consist of folded peptide chains, which in turn are made up of a series of amino acids. From stabilising cell structure to catalysing chemical reactions, proteins have many functions. Their diversity is further increased by modifications that take place after the peptide chains have been synthesised. One form of modification is protein splicing. The protein initially contains a so-called ‘intein’, which removes itself from the peptide chain to ensure the correct folding and function of the final protein.

A research team has now answered a long-standing research question: Why does a special variant of the inteins, the ‘split inteins’, often encounter problems in the laboratory that significantly lower the efficiency of the reaction? The researchers were able to identify protein misfolding as one cause and have developed a method to prevent it.

The splicing of proteins rarely occurs in nature but is very interesting for research. The solution found by the team opens up possibilities for using split inteins to produce proteins that are useful in basic research or for applications in biotechnology and biomedicine.

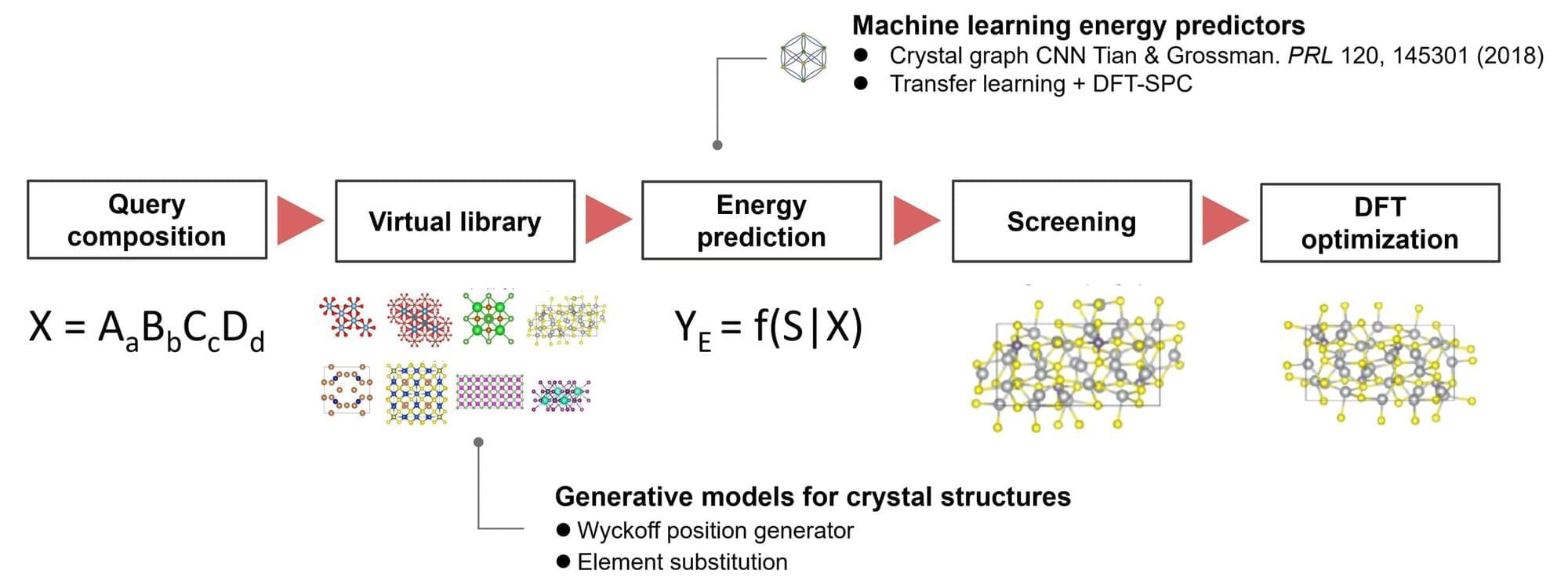

A research team from the Institute of Statistical Mathematics and Panasonic Holdings Corporation has developed a machine learning algorithm, ShotgunCSP, that enables fast and accurate prediction of crystal structures from material compositions. The algorithm achieved world-leading performance in crystal structure prediction benchmarks.

Crystal structure prediction seeks to identify the stable or metastable crystal structures for any given chemical compound adopted under specific conditions. Traditionally, this process relies on iterative energy evaluations using time-consuming first-principles calculations and solving energy minimization problems to find stable atomic configurations. This challenge has been a cornerstone of materials science since the early 20th century.

Recently, advancements in computational technology and generative AI have enabled new approaches in this field. However, for large-scale or complex molecular systems, the exhaustive exploration of vast phase spaces demands enormous computational resources, making it an unresolved issue in materials science.

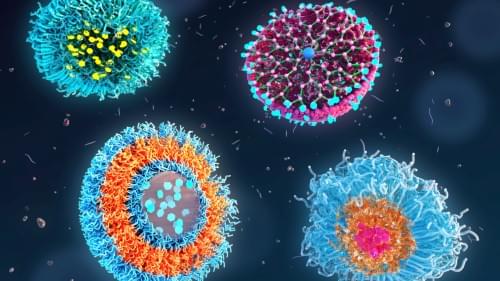

Imagine tiny LEGO pieces that automatically snap together to form a strong, flat sheet. Then, scientists add special chemical “hooks” to these sheets to attach glowing molecules called fluorophores.

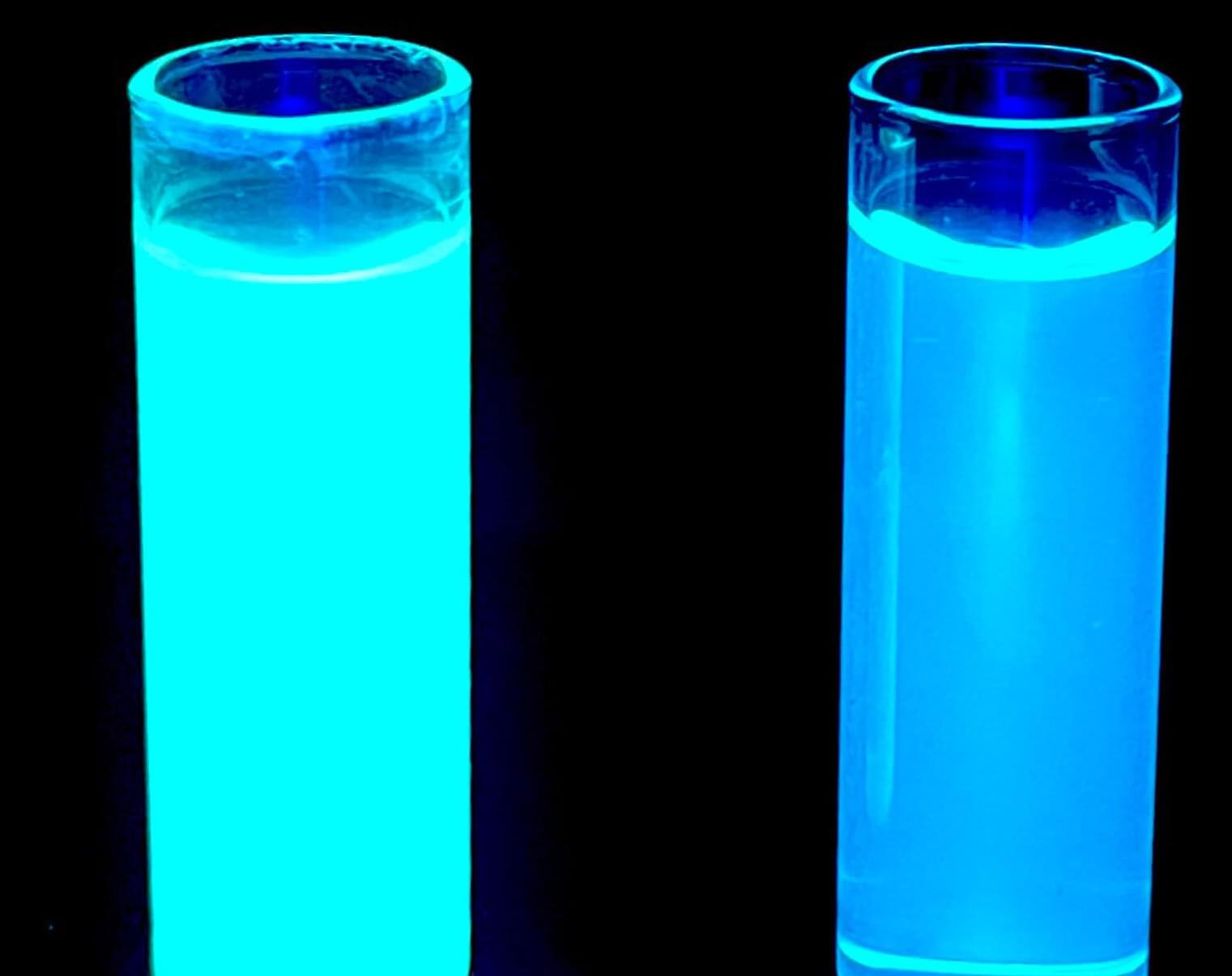

Associate Professor Gary Baker, Piyuni Ishtaweera, Ph.D., and their team have created these tiny, clay-based materials—called fluorescent polyionic nanoclays. They can be customized for many uses, including advancing energy and sensor technology, improving medical treatments and protecting the environment.

The work is published in the journal Chemistry of Materials.

Researchers at the National University of Singapore (NUS) have shown that a single, standard silicon transistor, the core component of microchips found in computers, smartphones, and nearly all modern electronics, can mimic the functions of both a biological neuron and synapse.

A synapse is a specialized junction between nerve cells that allows for the transfer of electrical or chemical signals, through the release of neurotransmitters by the presynaptic neuron and the binding of receptors on the postsynaptic neuron. It plays a key role in communication between neurons and in various physiological processes including perception, movement, and memory.

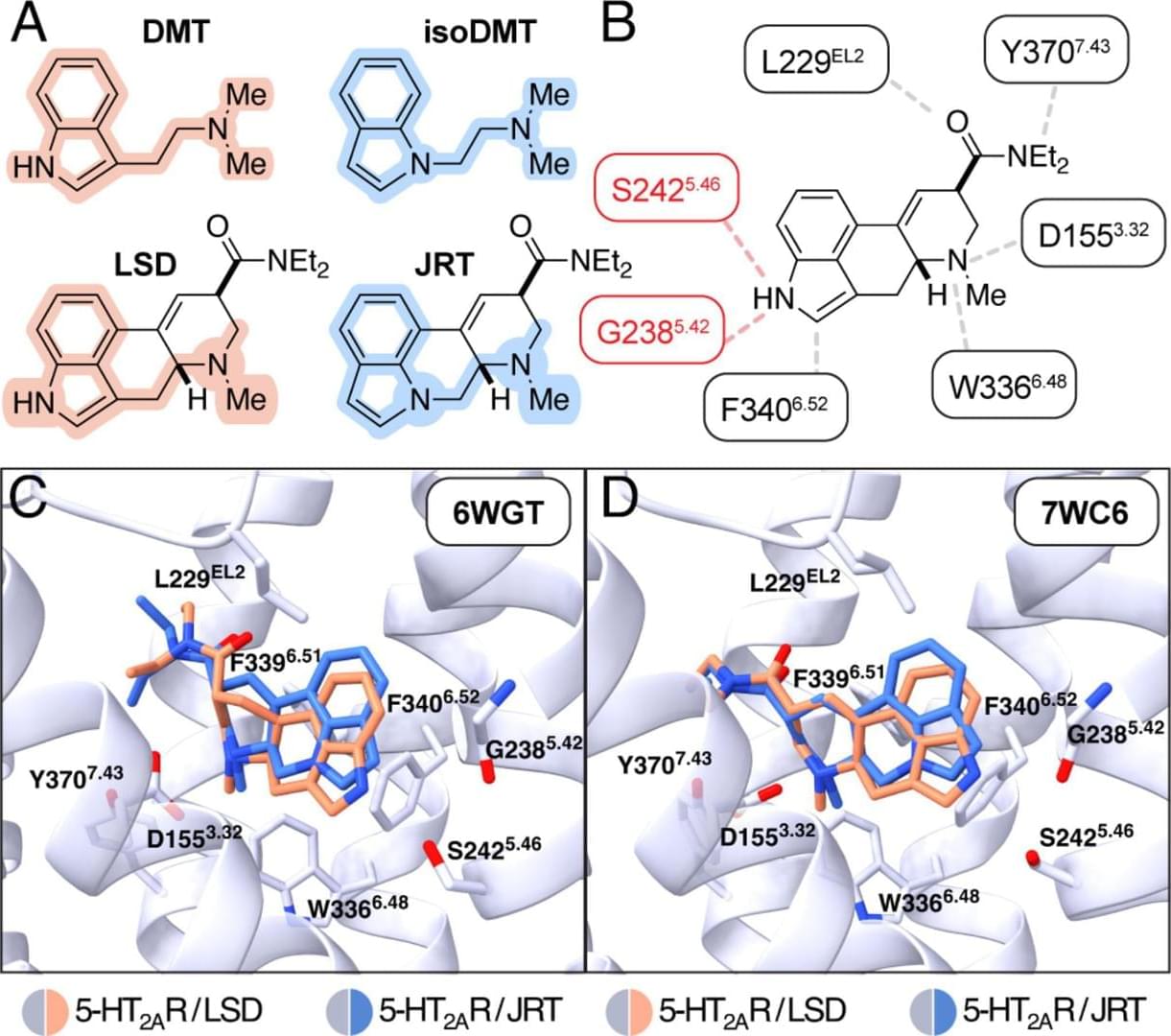

The research, published in [Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences](https://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.2416106122), highlights the new drug’s potential as a treatment option for conditions like schizophrenia, where psychedelics are not prescribed for safety reasons. The compound also may be useful for treating other neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases characterized by synaptic loss and brain atrophy.

To design the drug, dubbed JRT, researchers flipped the position of just two atoms in LSD’s molecular structure. The chemical flip reduced JRT’s hallucinogenic potential while maintaining its neurotherapeutic properties, including its ability to spur neuronal growth and repair damaged neuronal connections that are often observed in the brains of those with neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases.

Decreased dendritic spine density in the cortex is a key pathological feature of neuropsychiatric diseases including depression, addiction, and schizophrenia (SCZ). Psychedelics possess a remarkable ability to promote cortical neuron growth and increase spine density; however, these compounds are contraindicated for patients with SCZ or a family history of psychosis. Here, we report the molecular design and de novo total synthesis of (+)-JRT, a structural analogue of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) with lower hallucinogenic potential and potent neuroplasticity-promoting properties. In addition to promoting spinogenesis in the cortex, (+)-JRT produces therapeutic effects in behavioral assays relevant to depression and cognition without exacerbating behavioral and gene expression signatures relevant to psychosis.

Fiber optic cable deployed on a Swiss glacier has detected the seismic signals of crevasses opening in the ice, confirming that the technology could be useful in monitoring such icequakes, according to a report at the Seismological Society of America’s Annual Meeting.

Crevassing is important to the stability of glaciers, especially as they offer a pathway for meltwater to reach the rocky glacier bed to speed up the glacier’s movement and enhance melting. The harsh environment of a crevassed glacier, however, makes it difficult to place traditional seismic instruments to measure icequakes.

The source of seismic signals in an icequake differs from the shear forces of a tectonic earthquake or the explosive source of a chemical or nuclear detonation, explained Tom Hudson of ETH Zürich. A crevasse is a “crack source, where you have pure opening of a fracture just in one direction,” he said.

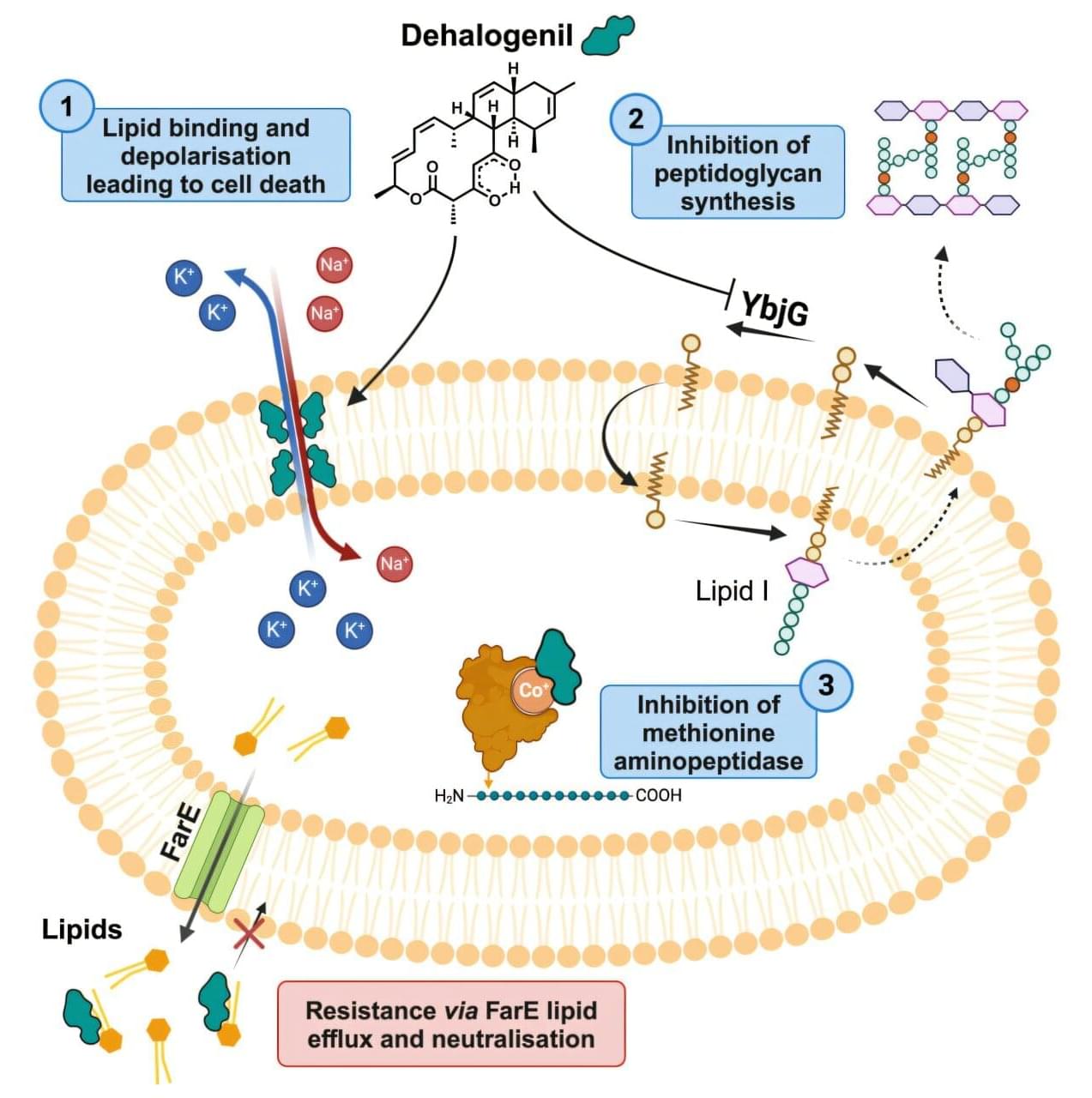

The development and spread of antibiotic resistance represents one of the greatest threats to global health. To overcome these resistances, drugs with novel modes of action are urgently needed.

Researchers at the Helmholtz Institute for Pharmaceutical Research Saarland (HIPS) have now uncovered the mode of action of a promising class of natural products—the chlorotonils. These molecules simultaneously target the bacterial cell membrane and the bacteria’s ability to produce proteins, enabling them to break through resistance. The team published its findings in Cell Chemical Biology.

The more frequently antibiotics are used, the faster pathogens evolve mechanisms to evade their effects. This leads to resistant pathogens against which common antibiotics are no longer effective. To ensure that effective treatments for bacterial infections remain available in the future, antibiotics that target different bacterial structures than currently approved drugs are essential.

Scientists have made a bold leap in the search for life’s origins, offering a fresh look at how chemistry might have crossed over into biology. At the center of this progress are coacervate droplets—tiny clusters of molecules that may be the missing link between lifeless matter and the first living cells.