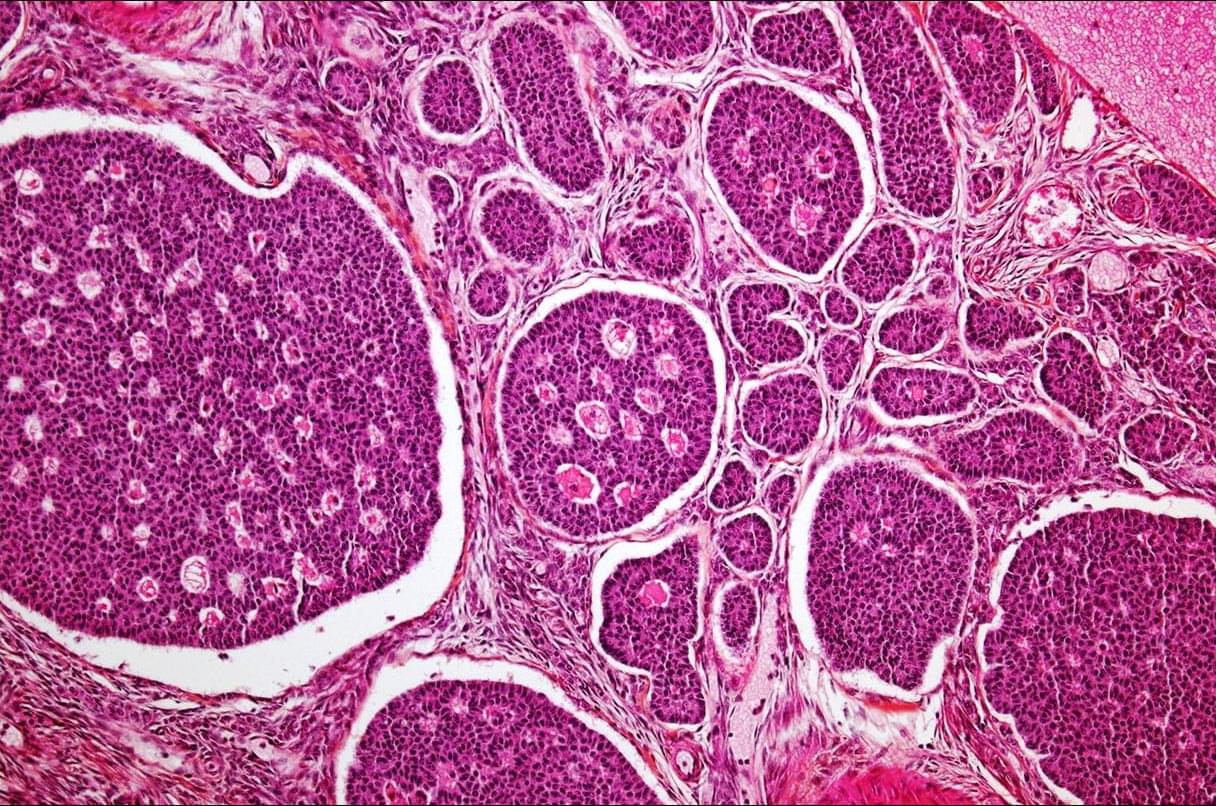

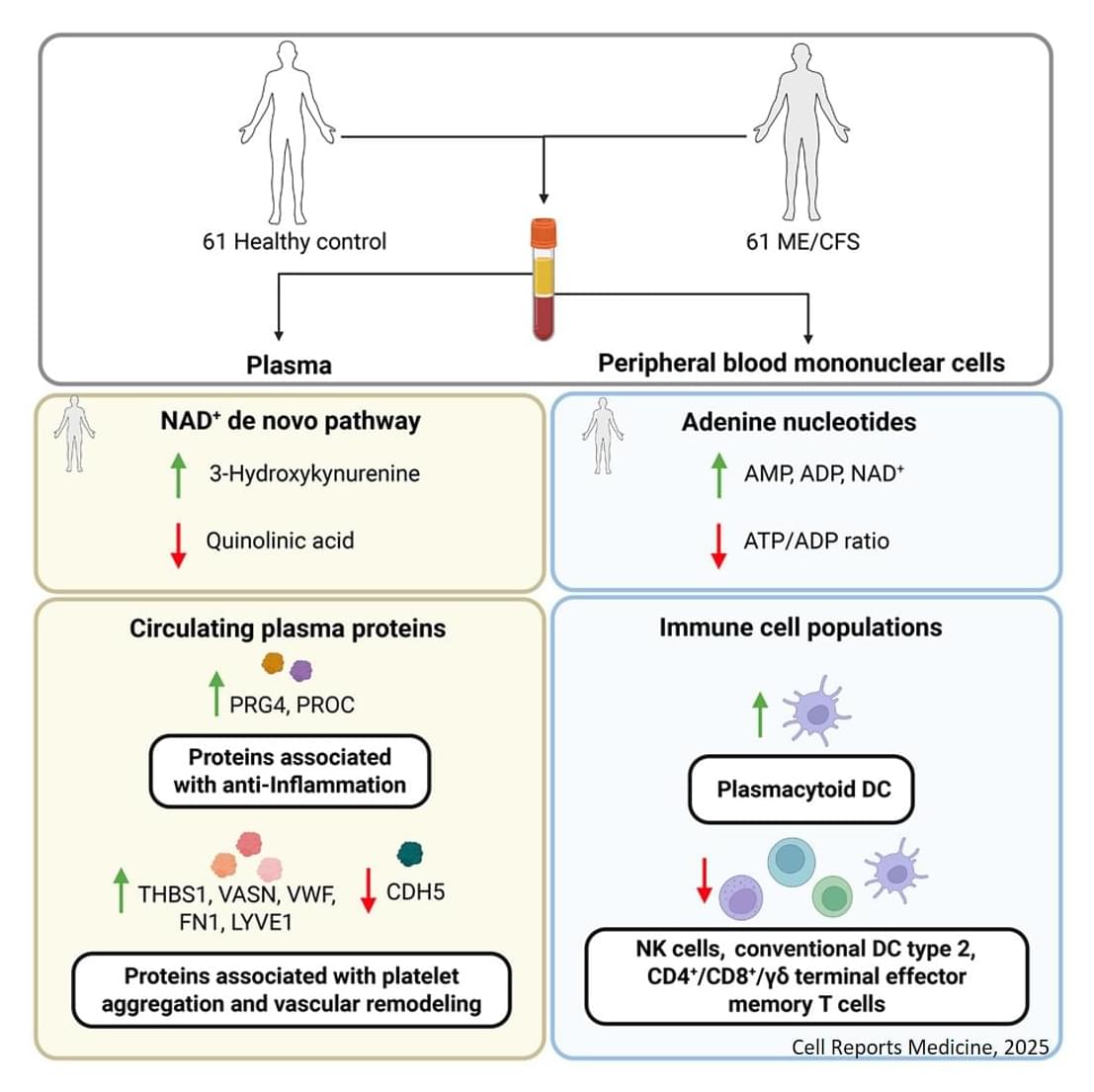

In a new study from Ian M. Mbano, Nuo Liu, Paul T. Elkington, Alex K. Shalek, Alasdair Leslie (University of KwaZulu-Natal) and colleagues, single-cell and spatial transcriptomics of human TB lung tissues from individuals in South Africa revealed that MMP1⁺CXCL5⁺ fibroblasts & SPP1⁺ macrophages are linked to TB disease & TB lung granuloma.

Ian M. Mbano, Nuo Liu, Marc H. Wadsworth, Mark J. Chambers, Thabo Mpotje, Osaretin E. Asowata, Sarah K. Nyquist, Kievershen Nargan, Duran Ramsuran, Farina Karim, Travis K. Hughes, Joshua D. Bromley, Robert Krause, Threnesan Naidoo, Liku B. Tezera, Michaela T. Reichmann, Sharie Keanne Ganchua, Henrik N. Kløverpris, Kaylesh J. Dullabh, Rajhmun Madansein, Sergio Triana, Adrie J.C. Steyn, Bonnie Berger, Mohlopheni J. Marakalala, Sarah M. Fortune, JoAnne L. Flynn, Paul T. Elkington, Alex K. Shalek, Alasdair Leslie; Single-cell and spatial profiling highlights TB-induced myofibroblasts as drivers of lung pathology. J Exp Med 2 March 2026; 223 : e20251067. doi: https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20251067

Download citation file: