This study looked at the longitudinal performance and potential utility of plasma p-tau217 as a primary endpoint in early-stage Alzheimer disease clinical trials.

Background and Objectives.

A large-scale screen of tuberculosis proteins has revealed several possible antigens that could be developed as a new vaccine for TB, the world’s deadliest infectious disease.

In the new study, a team of MIT biological engineers was able to identify a handful of immunogenic peptides, out of more than 4,000 bacterial proteins, that appear to stimulate a strong response from a type of T cells responsible for orchestrating immune cells’ response to infection.

There is currently only one vaccine for tuberculosis, known as BCG, which is a weakened version of a bacterium that causes TB in cows. This vaccine is widely administered in some parts of the world, but it poorly protects adults against pulmonary TB. Worldwide, tuberculosis kills more than 1 million people every year.

A new study analyzing the immune response to COVID-19 in a Catalan cohort of health workers sheds light on an important question: does it matter whether a person was first infected or first vaccinated?

According to the results, the order of the events does alter the outcome, at least when it comes to long-term protection against omicron.

The study, published in Nature Communications, was led by the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal) in collaboration with the Catalan Health Institute (ICS) and the Jordi Gol Institute (IDIAP JG), and with support from the Daniel Bravo Andreu Private Foundation (FPDBA).

A tiny percentage of our DNA—around 2%—contains 20,000-odd genes. The remaining 98%—long known as the non-coding genome, or so-called ‘junk’ DNA—includes many of the “switches” that control when and how strongly genes are expressed.

Now researchers from UNSW Sydney have identified the DNA switches that help control how astrocytes work—these are brain cells that support neurons, and are known to play a role in Alzheimer’s disease.

In research published in Nature Neuroscience, researchers from UNSW’s School of Biotechnology & Biomolecular Sciences described how they tested nearly 1,000 potential switches—strings of DNA known as enhancers—in human astrocytes grown in the lab. Enhancers can be located very far away from the gene they control, sometimes hundreds of thousands of DNA letters away—making them difficult to study.

New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University Medical Center investigators, with co-authors across additional US centers, report greater cognitive worsening at 78 weeks with valacyclovir than with placebo among adults with early symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease and herpes simplex virus (HSV) seropositivity.

Infectious diseases may contribute to Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. HSV-1 can become latent after oral infection, enter the brain via retrograde axonal transport, infiltrate the locus coeruleus, and migrate to the temporal lobe.

β-amyloid plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles are neuropathological features of Alzheimer’s disease. Animal models connect HSV-1 infection of neuronal and glial cells with a decrease in amyloid precursor protein, an increase in intracellular amyloid β-protein, and phosphorylation of tau protein.

One specific state, referred to as State 4, emerged as a key point of difference between the two groups. This state was characterized by strong connections between the left and right hemispheres of the brain. It specifically involved robust communication between the temporal and parietal regions, which are areas often associated with language and sensory processing.

The data showed that children with autism spent considerably less time in State 4 compared to the typically developing children. They also transitioned into and out of this state less frequently. The reduced time spent in this high-connectivity state was statistically distinct.

The researchers then compared these brain patterns to clinical assessments of the children. They found a correlation between the brain data and the severity of autism symptoms. Children who spent the least amount of time in State 4 tended to have higher scores on standardized measures of autism severity.

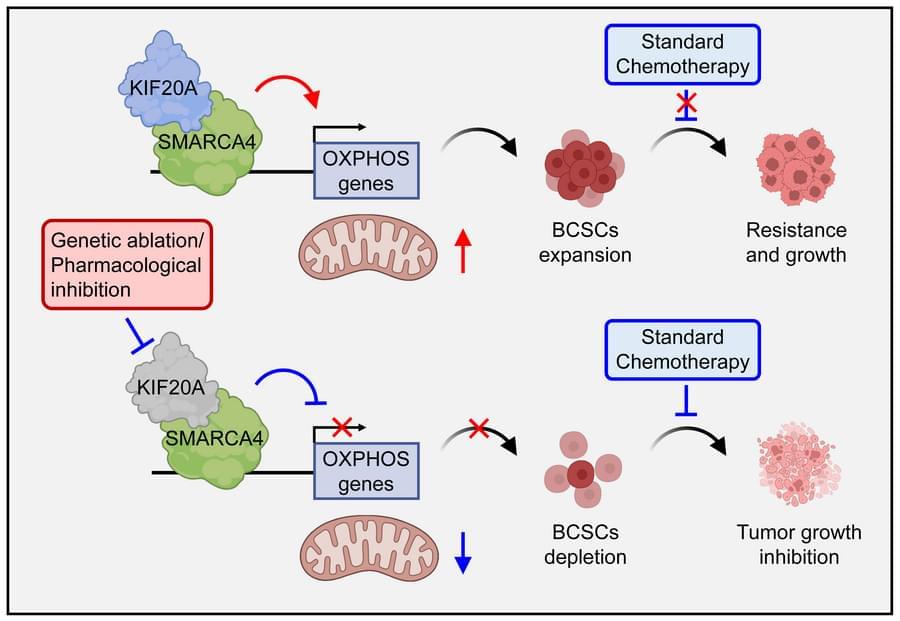

Here, Qing Zhang & team show targeting kinesin family member KIF20A in vitro and in mice sensitizes stem-like TNBC cells to standard chemotherapy.

1Department of Pathology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, USA.

2Department of Breast and Endocrine Surgery, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya, Aichi, Japan.

3Jinfeng Laboratory, Chongqing, China.

4Quantitative Biomedical Research Center, Peter O’Donnell Jr. School of Public Health, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, USA.

Until AlphaFold’s debut in November 2020, DeepMind had been best known for teaching an artificial intelligence to beat human champions at the ancient game of Go. Then it started playing something more serious, aiming its deep learning algorithms at one of the most difficult problems in modern science: protein folding. The result was AlphaFold2, a system capable of predicting the three-dimensional shape of proteins with atomic accuracy.

Its work culminated in the compilation of a database that now contains over 200 million predicted structures, essentially the entire known protein universe, and is used by nearly 3.5 million researchers in 190 countries around the world. The Nature article published in 2021 describing the algorithm has been cited 40,000 times to date. Last year, AlphaFold 3 arrived, extending the capabilities of artificial intelligence to DNA, RNA, and drugs. That transition is not without challenges—such as “structural hallucinations” in the disordered regions of proteins—but it marks a step toward the future.

To understand what the next five years holds for AlphaFold, WIRED spoke with Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at DeepMind and architect of its AI for Science division.

Restoring Sight For Those In Need — Dr. Edward J. Holland, M.D. & Robert Dempsey — Co-Founders — Holland Foundation For Sight Restoration

Dr. Edward Holland is a world-renowned leader in corneal transplantation and severe ocular surface disease, and is the Co-Founder of the Holland Foundation for Sight Restoration (HFSR — https://www.hollandfoundationforsight… is a 501©(3) nonprofit organization, dedicated to transforming the lives of individuals affected by these conditions, including limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD) – a rare and devastating condition that can result in chronic pain, profound vision loss, and blindness.

Through this HFSR initiative, Centers of Excellence (COEs) focused on the advanced sight restoration procedures of Ocular Surface Stem Cell Transplantation (OSST) are being launched across the country. As part of its mission, the foundation is also committed to broadening education and training so that more physicians nationwide can learn and implement The Cincinnati ProtocolTM for the management of these patients.

Dr. Holland is also the Director of Cornea Services at Cincinnati Eye Institute (https://www.cincinnatieye.com/doctors…) and Professor of Ophthalmology at the University of Cincinnati (https://med.uc.edu/landing-pages/prof…).

Dr. Holland attended the Loyola-Stritch School of Medicine in Chicago and trained in Ophthalmology at the University of Minnesota. He completed a fellowship in cornea and external disease at the University of Iowa and then completed a second fellowship in ocular immunology at the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland.

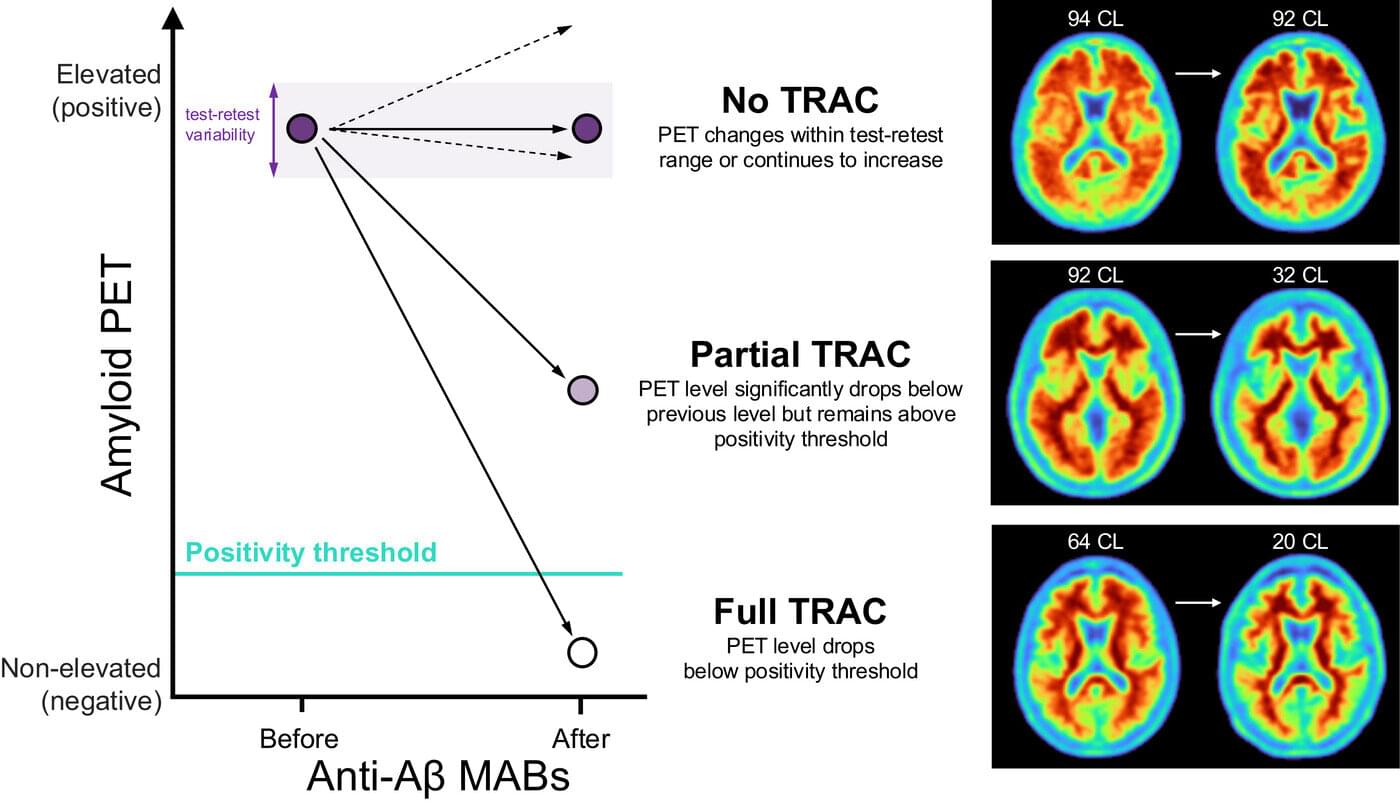

In the last few years, progress has been made in the fight against Alzheimer’s disease with a class of therapies called anti-amyloid antibodies (anti-Aβ). These monoclonal anti-Aβs are proteins made in a laboratory to stimulate the immune system to slow the progression of the disease by targeting amyloid plaques in the brain that are characteristic of Alzheimer’s.

Biomarkers, such as measures derived from PET scans that reflect amyloid plaques in the brain, were instrumental in FDA approval of anti-Aβ therapies, like lecanumab (Leqembi) and donanemab (Kisulna), and have been shown to reduce plaques in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients. Yet despite FDA approval, there is still a clinical need to better understand how to monitor the efficacy and safety of these treatments.

To this end, the Alzheimer’s Association convened a workgroup of scientists and clinicians with experience in Alzheimer’s disease, including clinical trials of anti-Aβ therapies and biomarkers, to propose a framework to characterize the response of patients receiving these treatments.