Category: biotech/medical – Page 2,646

Stem cells could be used to grow back teeth, scientists believe

Lost and broken teeth could one day be regrown, scientists believe after finding the stem cells responsible for tooth formation and the gene that switches it on.

Scientists at the University of Plymouth discovered a new group of stem cells which form skeletal tissue and contribute to the making dentin — the hard tissue that surrounds the main body of the tooth. They also showed that a gene called Dlk1 sparks the stem cells into action, so they can mend damage such as decay, crumbling or cracked teeth.

Currently there is nothing to be done to repair damaged teeth apart from fillings or crowns.

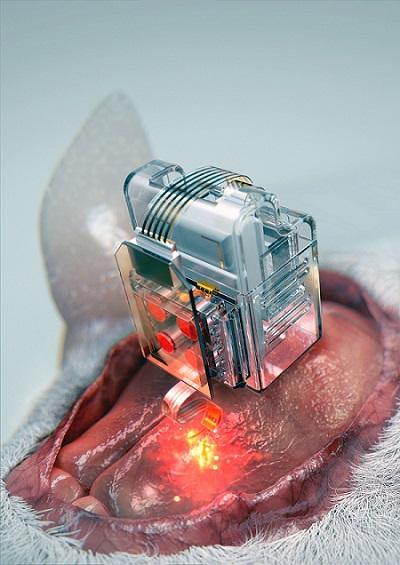

Manipulating brain cells

Researchers have developed a soft neural implant that can be wirelessly controlled using a smartphone. It is the first wireless neural device capable of indefinitely delivering multiple drugs and multiple colour lights, which neuroscientists believe can speed up efforts to uncover brain diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, addiction, depression, and pain. A team under Professor Jae-Woong Jeong from the School of Electrical Engineering at KAIST and his collaborators have invented a device that can control neural circuits using a tiny brain implant controlled by a smartphone. The device, using Lego-like replaceable drug cartridges and powerful, low-energy Bluetooth, can target specific neurons of interest using drugs and light for prolonged periods. This study was published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

“This novel device is the fruit of advanced electronics design and powerful micro and nanoscale engineering,” explained Professor Jeong. “We are interested in further developing this technology to make a brain implant for clinical applications.”

Tentacled microbe could be missing link between simple cells and complex life

Patience proved the key ingredient to what researchers are saying may be an important discovery about how complex life evolved. After 12 years of trying, a team in Japan has grown an organism from mud on the seabed that they say could explain how simple microbes evolved into more sophisticated eukaryotes. Eukaryotes are the group that includes humans, other animals, plants, and many single-celled organisms. The microbe can produce branched appendages, which may have helped it corral and envelop bacteria that helped it—and, eventually, all eukaryotes—thrive in a world full of oxygen.

“This is the work that many people in the field have been waiting for,” says Thijs Ettema, an evolutionary microbiologist at Wageningen University in the Netherlands. The finding has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal, but on Twitter, other scientists reviewing a preprint on it have already hailed it as the “paper of the year” and the “moon landing for microbial ecology.”

The tree of life has three major branches—bacteria and archaea make up two, both of which are microbes that lack nuclei and mitochondria, distinct membrane-bound compartments to store DNA or generate energy, respectively. Those components, or organelles, characterize cells of the third branch, the eukaryotes. The prevailing thinking is that roughly 2 billion years ago, a microbe belonging to a group called the Asgard archaea absorbed a bacterium called an alphaproteobacterium, which settled inside and became mitochondria, producing power for its host by consuming oxygen as fuel. But isolating and growing Asgard archaea has proved a challenge, as they tend to live in inhospitable environments such as deep-sea mud. They also grow very slowly, so they are hard to detect. Most evidence of their existence so far has been fragments of DNA with distinctive sequences.

CRISPR Gene Editing Is Being Tested In Human Patients And Scientists Admit They Do Not Know “What The Long-Term Effects Of Man-Made Edits To The Human Genome Might Have”

Scientists agree that CRISPR holds great promise in giving researchers unprecedented power to snip out abnormal stretches of DNA, But there are still significant questions about how safe and effective CRISPR gene editing will be once it’s unleashed in the human body. CRISPR works well enough in the lab, in a dish of human cells, but as with any technology, there are glitches. Some studies have shown that the gene editing goes awry once in a while, splicing incorrect places in the genome. Then there is the bigger question of what longer term, unanticipated effects man-made edits to the human genome might have… (READ MORE)

Has this scientist finally found the fountain of youth?

The black mouse on the screen sprawls on its belly, back hunched, blinking but otherwise motionless. Its organs are failing. It appears to be days away from death. It has progeria, a disease of accelerated aging, caused by a genetic mutation. It is only three months old.

I am in the laboratory of Juan Carlos Izpisúa Belmonte, a Spaniard who works at the Gene Expression Laboratory at San Diego’s Salk Institute for Biological Studies, and who next shows me something hard to believe. It’s the same mouse, lively and active, after being treated with an age-reversal mixture. “It completely rejuvenates,” Izpisúa Belmonte tells me with a mischievous grin. “If you look inside, obviously, all the organs, all the cells are younger.”

Izpisúa Belmonte, a shrewd and soft-spoken scientist, has access to an inconceivable power. These mice, it seems, have sipped from a fountain of youth. Izpisúa Belmonte can rejuvenate aging, dying animals. He can rewind time. But just as quickly as he blows my mind, he puts a damper on the excitement. So potent was the rejuvenating treatment used on the mice that they either died after three or four days from cell malfunction or developed tumors that killed them later. An overdose of youth, you could call it.

Bill Faloon: A Life Long Quest To Reverse Human Aging!

Ira Pastor, ideaXme longevity and aging Ambassador and Founder of Bioquark interviews Bill Faloon, Director and Co-Founder, Life Extension Foundation and Founder of The Church Of Perpetual Life.

Ira Pastor Comments:

On the last several shows we have spent time on different hierarchical levels the biologic-architecture of the life, disease and aging process. We’ve spent some time talking about the genome, the microbiome, tissue engineering, systems biology, and dabbled a bit in the areas of quantum biology, organism hydro-dynamics, and even chronobiology.

As exciting and promising as all these research paths are, at the end of the day, in order for them to yield what many people are looking for, that is radically extended healthspans and lifespans, there needs to be an organized system of human translation build around them, integrating these various products, services and technologies, from supplements, to biologics, to functional foods, to cosmeceuticals, to various physio-therapeutic interventions, and so forth, as well as all the related supporting advocacy and education, as biologic aging is truly a multi-factorial, combinatorial process that is never going to be amenable to big pharma’s traditional “single magic bullet” philosophy that it promoted throughout the last century.

For today’s guest, I could think of no one better to talk with us about this topic and take us into the future on this front, than Bill Faloon, Director and Co-Founder, Life Extension Foundation (LEF), a consumer advocacy organization with over 100,000 members that funds research (investing million per year in researchers around the globe) and disseminates information to consumers about optimal health, and more recently in the area of actionable clinical interventions regarding human biologic age reversal, through a fascinating new project called the Age Reversal Network, defined as an open-source communications channel to exchange scientific information, foster strategic alliances, and support biomedical endeavors aimed at reversing degenerative aging.

Bill is also the Founder of The Church Of Perpetual Life, a nonprofit transhumanist organization aiming to combine discussion integrating spirituality, community, and aging scientific research in a single unified forum.

He’s a board member of the Coalition For Radical Life Extension, which is the organizer of annual RAADfest conference (Revolution Against Aging and Death) which is the world’s largest gathering of radical life extension enthusiasts.

Young blood cocktail stops Alzheimer’s decline, early clinical trial reports

Alkahest, a California-based biotech start-up, has just revealed some compelling early results from an ongoing Phase 2 trial into the efficacy of its novel formulation of plasma proteins derived from young blood, developed to slow, or even stop, the cognitive decline associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

Thousands of “indestructible” tardigrades could be living on the moon after spaceship crash

The tardigrades were part of a “lunar library” that Spivack’s foundation had put together. According to Wired, the package was about the size of a DVD and contained human DNA—including Spivack’s own—as well as 30 million pages of information on mankind’s knowledge and thousands of dehydrated tardigrades.

Tardigrades are known as one of the toughest creatures on Earth. They are microscopic, measuring about 0.012 to 0.020 inches in length, and can withstand temperatures of up to 304 degrees Fahrenheit and can survive being frozen alive. One tardigrade is known to have survived being frozen for 30 years. They can also live without water for up to a decade by shriveling up and placing themselves in a state of suspended animation—a trait DARPA is currently studying in the hope of preserving soldiers injured on the battlefield.

China’s CRISPR push in animals promises better meat, novel therapies, and pig organs for people

In addition to having access to large colonies of monkeys and other species, animal researchers in China face less public scrutiny than counterparts in the United States and Europe. Ji, who says his primate facility follows international ethical standards for animal care and use, notes that the Chinese public has long supported monkey research to help human health. “Our religion or our culture is different from that of the Western world,” he says. Yet he also recognizes that opinions in China are evolving. Before long, he says, “We’ll have the same situation as the Western world, and people will start to argue about why we’re using a monkey to do an experiment because the monkey is too smart, like human beings.”

This story, one in a series, was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

BEIJING, GUANGZHOU, JIANGMEN, KUNMING, AND SHANGHAI—Early one February morning, researchers harvest six eggs from a female rhesus macaque—one of 4000 monkeys chirping and clucking in a massive outdoor complex of metal cages here at the Yunnan Key Laboratory of Primate Biomedical Research. On today’s agenda at the busy facility, outside Kunming in southwest China: making monkey embryos with a gene mutated so that when the animals are born 5 months later, they will age unusually fast. The researchers first move the eggs to a laboratory bathed in red light to protect the fragile cells. Using high-powered microscopes, they examine the freshly gathered eggs and prepare to inject a single rhesus sperm into each one. If all goes well, the team will introduce the genome editor CRISPR before the resulting embryo begins to grow—early enough for the mutation for aging to show up in all cells of any offspring.

But as often happens when eggs are retrieved, all does not go well. Only one egg in this morning’s batch is mature enough to fertilize. “We were a little unlucky today,” says Niu Yuyu, who with facility director Ji Weizhi runs the gene-editing research. The group can afford a little bad luck, though. Through a combination of patience, ingenuity, and enormous animal resources, the team has already used CRISPR to create an astonishing range of genome-edited monkeys to serve as models for studying human diseases.