Soft 3D electronic mesh wraps mini brains, records 91% of neural activity for drug testing and research.

Sink your teeth into this.

Japanese scientists are advancing human clinical trials of a drug that could allow people to regrow lost teeth.

The treatment targets a gene called USAG1, which normally shuts down tooth development after your adult teeth come in. By blocking that gene, researchers are essentially restarting the body’s natural tooth-growth process.

Phase I trials began in September 2024 with 30 adult men missing at least one tooth. If successful, the treatment could potentially be available by around 2030.

Dentures? Implants?

What if you could just… grow a new tooth?

Would you try this?

This study provides detailed electro-clinical characterization of surgically treated MOGHE patients and highlights the impact of SEEG on their outcome.

Objective Epilepsy surgery is an effective treatment option for patients with medically refractory epilepsy due to mild malformation of cortical development with oligodendroglial hyperplasia (MOGHE). The success of surgery depends on the accurate localization of the epileptogenic zone, which can be challenging due to the subtle imaging features. The aim of this project was to provide an in-depth electro-clinical characterization of MOGHE in patients with medically intractable epilepsy, and to assess the role of stereo-electroencephalography (SEEG) in tailoring the resection and optimizing surgical outcome.

In a new study, published in Cell, researchers describe a newfound mechanism for creating proteins in a giant DNA virus, comparable to a mechanism in eukaryotic cells. The finding challenges the dogma that viruses lack protein synthesis machinery, and blurs the line between cellular life and viruses.

Protein production is accomplished in cellular life by decoding messenger RNA (mRNA) sequences in a process referred to as translation. In fact, most genes have some function related to protein synthesis. However, viruses are not and do not contain cells.

“In contrast to living organisms, viruses cannot replicate independently and rely on a host cell to perform many of the biological processes required to reproduce. Although viruses encode proteins involved in DNA replication and transcription, the dogma is that all viruses share a universal dependence on the host cell translation machinery for viral protein synthesis,” explain the authors of the new study.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have developed a method to predict when someone is likely to develop symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease using a single blood test. In a study published in Nature Medicine, the researchers demonstrated that their models predicted the onset of Alzheimer’s symptoms within a margin of three to four years.

This method could have implications both for clinical trials developing preventive Alzheimer’s treatments and for eventually identifying individuals likely to benefit from these treatments.

More than seven million Americans live with Alzheimer’s disease, with health and long-term care costs for Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia projected to reach nearly $400 billion in 2025, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. This massive public health burden currently has no cure, but predictive models could help efforts to develop treatments that prevent or slow the onset of Alzheimer’s symptoms.

As aging populations and rising diabetes rates drive an increase in chronic wounds, more patients face the risk of amputations. UC Riverside researchers have developed an oxygen-delivering gel capable of healing injuries that might otherwise progress to limb loss.

Injuries that fail to heal for more than a month are considered chronic wounds. They affect an estimated 12 million people annually worldwide, and around 4.5 million in the U.S. Of these, about one in five patients will ultimately require a life-altering amputation.

The new gel, tested in animal models, targets what researchers believe is a root cause of many chronic wounds: a lack of oxygen in the deepest layers of the damaged tissue. Without sufficient oxygen, wounds languish in a prolonged state of inflammation, allowing bacteria to flourish and tissue to deteriorate rather than regenerate.

Traumatic injury is the third leading cause of death in the state of Texas, surpassing strokes, Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A massive number of these deaths are the result of uncontrolled bleeding. “Severe blood loss can rapidly lead to hemorrhagic shock,” said Dr. Akhilesh Gaharwar, a biomedical engineering professor at Texas A&M University. “Many patients die within one to two hours of injury. This critical period is often referred to as the ‘golden hour.’”

Gaharwar and his fellow researchers in the biomedical engineering department have found a way to extend this golden hour—using clay.

Gaharwar, Dr. Duncan Maitland and Dr. Taylor Ware are developing a suite of injectable hemostatic bandages —biomedical materials that stop bleeding and promote blood to clot faster. Their research is specifically targeting deep internal bleeding where traditional methods like compression are not possible.

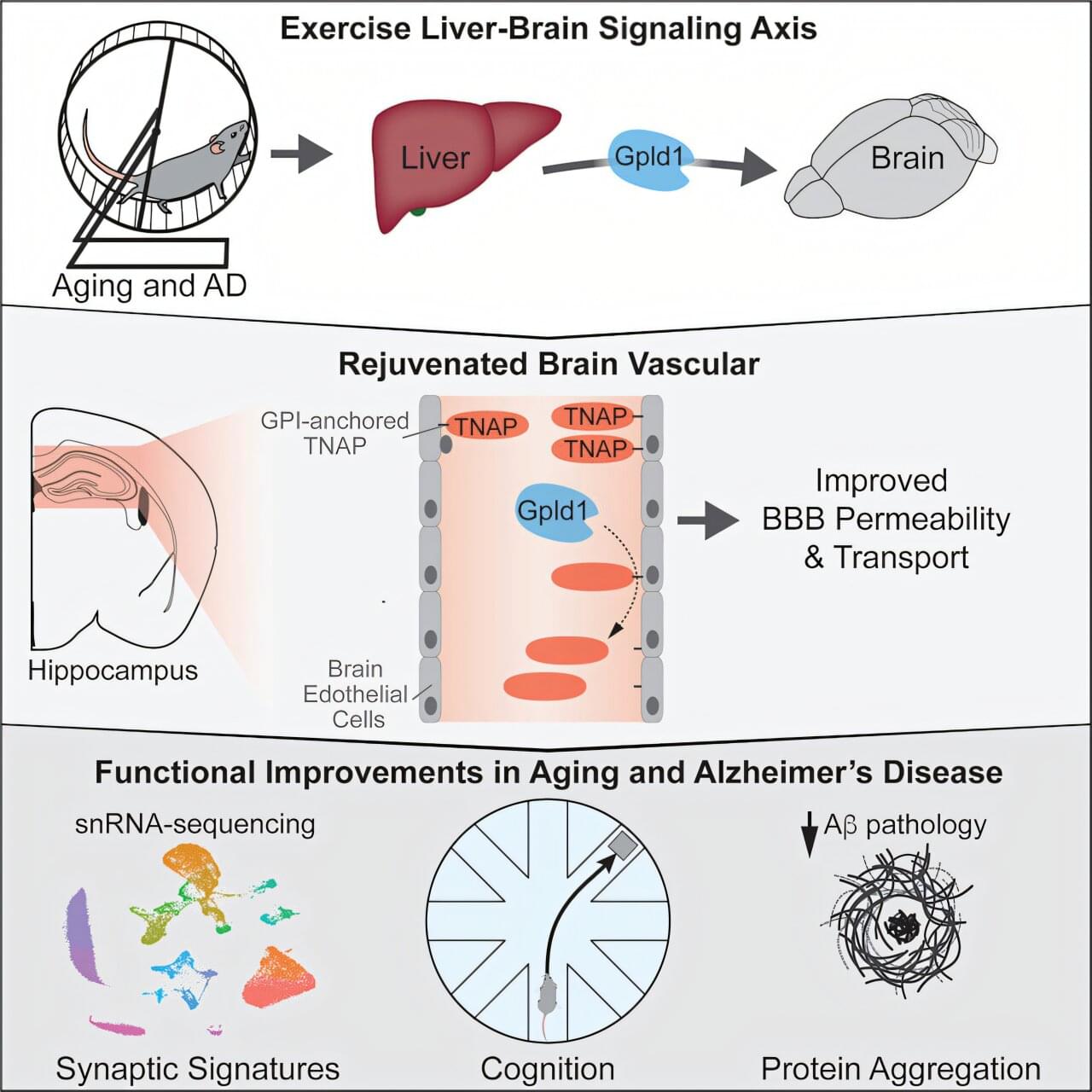

Researchers at UC San Francisco have discovered a mechanism that could explain how exercise improves cognition by shoring up the brain’s protective barrier. With age, the network of blood vessels—called the blood–brain barrier—gets leaky, letting harmful compounds enter the brain. This causes inflammation, which is associated with cognitive decline and is seen in conditions like Alzheimer’s disease. The research is published in the journal Cell.

Six years ago, the team identified a brain-rejuvenating enzyme called GPLD1 that mice produced in their livers when they exercised. But they couldn’t understand how it worked, because it cannot get into the brain.

The new study answers that question. Researchers discovered that GPLD1 was working through another protein called TNAP. As the mice age, the cells that form the blood-brain barrier accumulate TNAP, which makes it leaky. But when mice exercise, their livers produce GPLD1. It travels to the vessels that surround the brain and trims TNAP off the cells.