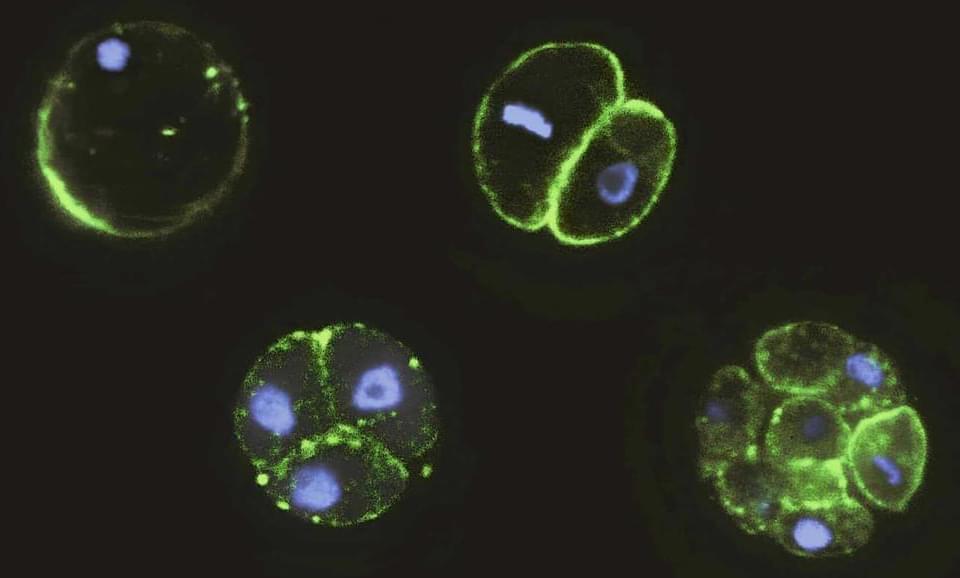

Peptides can form on cosmic dust despite water presence, challenging previous beliefs and suggesting a possible extraterrestrial origin for life’s building blocks.

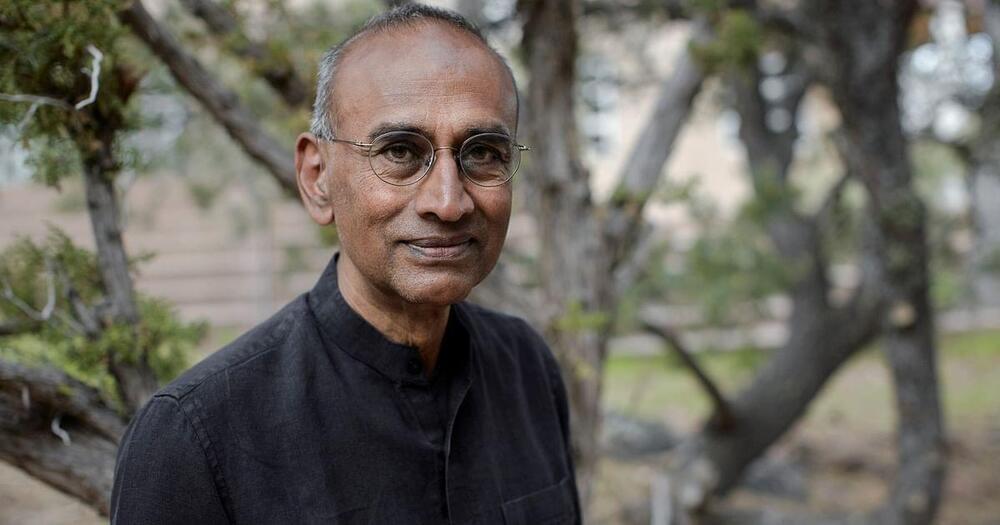

Peptides are organic compounds that play a crucial role in many biological processes, for example, as enzymes. A research team led by Dr. Serge Krasnokutski from the Astrophysics Laboratory at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy at the University of Jena had already demonstrated that simple peptides can form on cosmic dust particles. However, it was previously assumed that this would not be possible if molecular ice, which covers the dust particle, contains water – which is usually the case.

Now, the team, in collaboration with the University of Poitiers, France, has discovered that the presence of water molecules is not a major obstacle for the formation of peptides on such dust particles. The researchers report on their findings in the journal Science Advances.