http://www.blogtalkradio.com/dr-jeanette-gallagher/2018/03/0…sformation

Two pivotal conferences on the topic of “death” coming up!!

First at the INSERM Liliane Bettencourt School on March 16–18 will be “Death: From Cells to Societies — Aging, Dying, and Beyond” -

Then, April 11–13 at Harvard Medical School, will be “Defining Death: Organ transplantation and the 50-year legacy of the Harvard report on brain death”

http://bioethics.hms.harvard.edu/annual-bioethics-conference-2018

An important inflection point for all!!

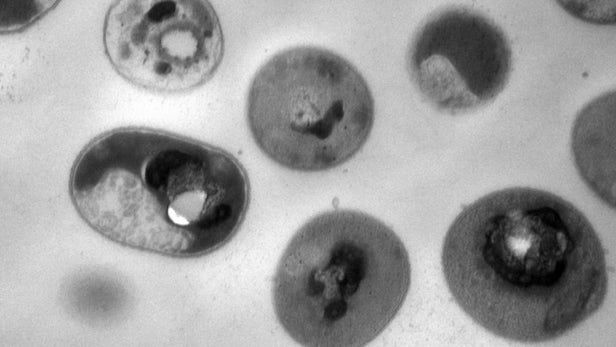

A research team composed of scientists from the Institute of Bioengineering and Nanotechnology (IBN) of the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) and IBM Research has produced a new synthetic molecule that can target and kill five multidrug-resistant bacteria. This synthetic polymer was found to be non-toxic and could enable entirely new classes of therapeutics to address the growing problem of antibiotic-resistant superbugs.

The synthetic molecules are called guanidinium-functionalized polycarbonates and were found to be both biodegradable and non-toxic to human cells. Essentially, the positively-charged synthetic polymer enters a living body and binds specifically to certain bacteria cells by homing in on a microbial membrane’s related negative charge. Once attached to the bacteria, the polymer crosses the cell membrane and triggers the solidification of proteins and DNA in the cell, killing the bacteria.

Biohacking future of avoiding doctors?

This man claims experimental gene therapy cured his lactose intolerance.

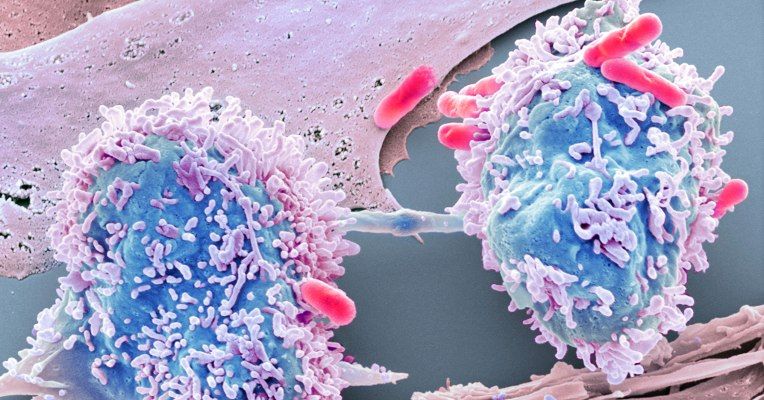

A who’s-who from the world of synthetic biological research have come together to launch Senti Biosciences with $53 million in funding from a slew of venture capital investors.

Led by Tim Lu, a longtime researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and one of the founding fathers of synthetic biology, Senti’s aim is nothing less than developing therapies that are tailored to an individual’s unique biology — and their first target is cancer.

Here’s how Lu described a potential cancer treatment using Senti’s technology to me. “We take a cell derived from humans that we can insert our genetic circuits into… we insert the DNA and encoding and deliver those cells via an IV infusion. We have engineered the cells to locate where the tumors are… What we’ve been doing is engineering those cells to selectively trigger an immune response against the tumor.”