For the first time ever researchers have had a breakthrough in creating a cocktail of drugs that caused new neurons to grow in the brains of mice.

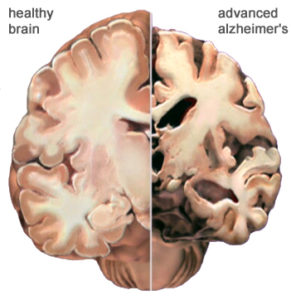

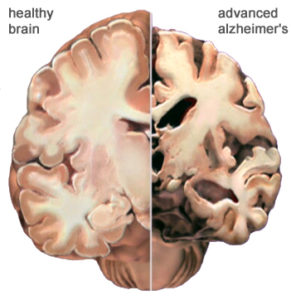

In my last article I gave a detailed account on the debate of neurogenesis. While some neuroscientists claim that neurogenesis takes place within the adult mammalian human brain other researchers contest that idea claiming that new neurons stop developing at a very young age. Whichever side of the debate you are on one thing remains certain, that there are neurological diseases that leave negative impacts on cognitive function. This has left researchers looking for various ways to treat Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and other brain damage.

While the brain is incredibly complex and past research has failed to offer much hope for Alzheimer’s disease, Hongkui Deng at Paking University Health Science Center in China may finally be able to change that.

For the first time ever researchers have had a breakthrough in creating a cocktail of drugs that caused new neurons to grow in the brains of mice.

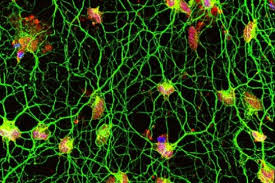

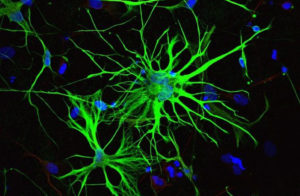

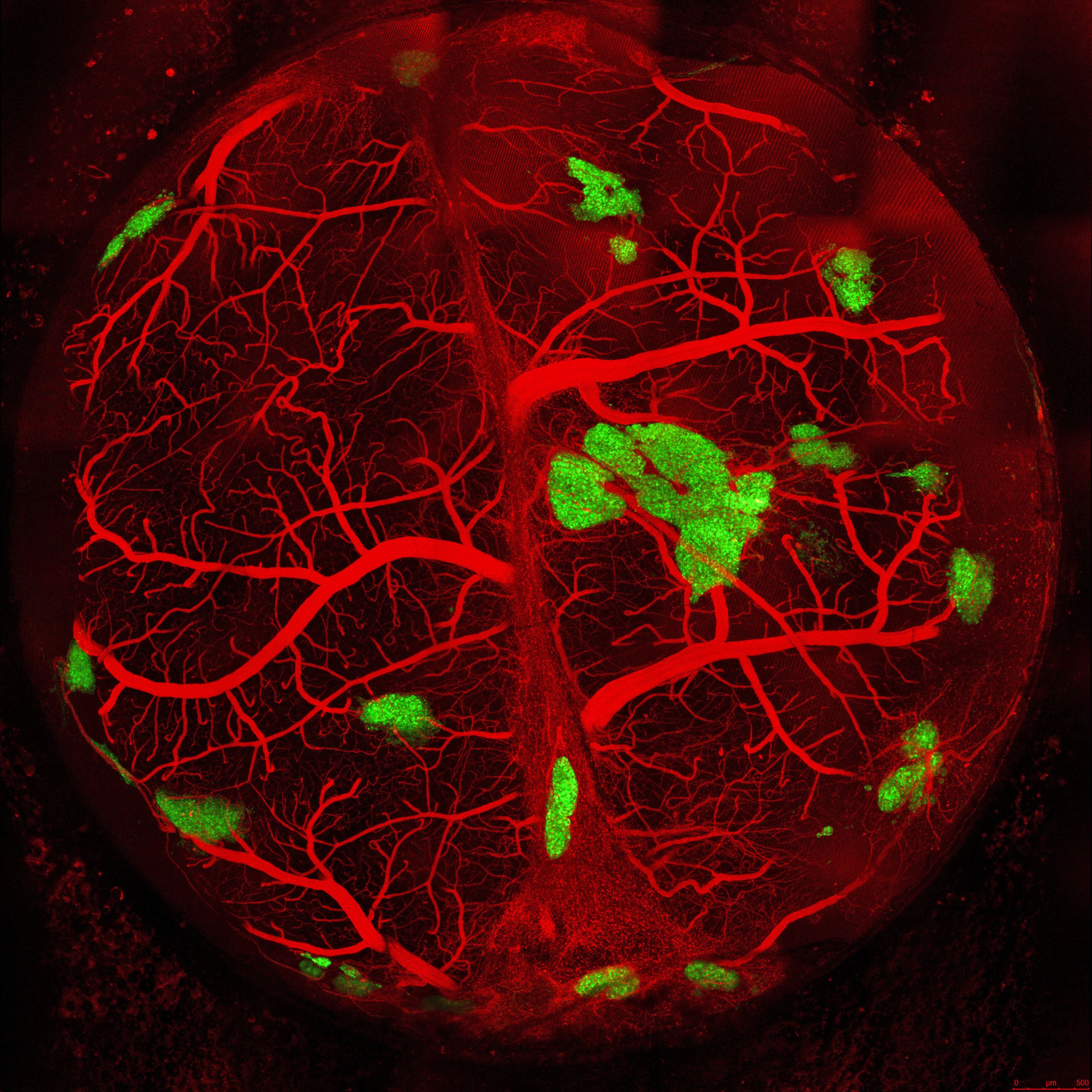

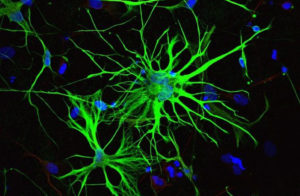

What this cocktail does when injected into the brain is it hijacks the astrocytes into behaving like new neurons. This is significant for a number of reasons. One important detail about astrocyte cells is that they can survive after a stroke while regular neurons die. Another important detail is that there are 10 times more astrocytes in the brain than neurons. That means that there are 1 trillion glia cells within the brain. So not only are they more resilient than neurons they outnumber them too.

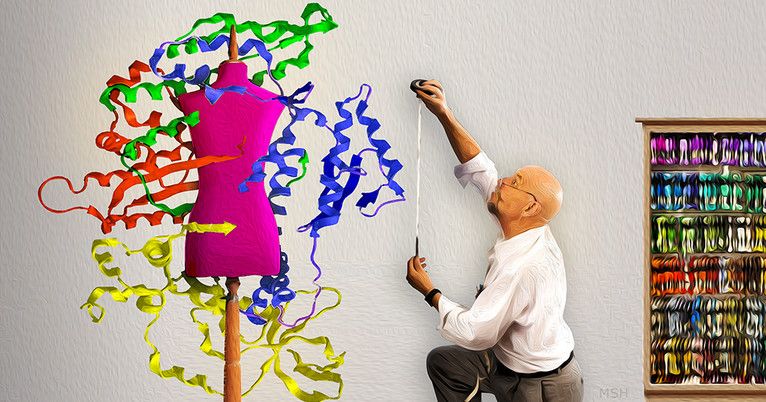

Deng and his team of researchers have found that when the cocktail is injected into the brains of mice that it effectively gives the cell a new identity by erasing its old one and giving it a new one. Not only did the cells change shape but they showed change in gene activity too.

The results were substantial. While it remains speculative as to how closely the cells resemble normal neurons, around 80 to 90 per cent of the astrocytes started to resemble neurons and even mimicked their behavior by electrical signals the same way regular neurons do.

“They are unlikely to be a 100 percent match” Deng stated. “But the treatment was safe and none of the mice developed any health problems”.

Matthew Grubb at King’s College London states that “if it holds up it’s absolutely amazing, and has a lot of potential applications and exciting consequences. If you’ve got a degenerating brain, for example in Alzheimer’s disease, and you could get the brain to regrow neurons itself, it would be a huge step forward.”

The next step for the researchers will be to test the cocktail in mice that have had a stroke. The hope is that the cocktail will cause the astrocytes to behave as neurons and help the mice recover.

While Grubb admits it is difficult to predict the effects of the treatment in humans, if it works in mice then it offers new hope for those who suffer from neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s. While it is unlikely to bring back lost memories Grubb thinks it might restore the ability to create new ones.

Even though the research is promising there still remain challenges as Roger Barker at the University of Cambridge points out. The sheer numbers of cells lost in a neurodegenerative disease is something to consider. “In Parkinson’s, a quarter of a million cells are lost from either side of the brain. Currently Barker is conducting clinical trials of implants of brain tissue taken from aborted fetuses as a treatment for Parkinson’s.

Another challenge is to distinguish the types of neurons the drugs will make. As Grubb points out, if you make too many of the type of neurons that excites their neighbors you end up triggering epilepsy. Grubb also points out that different brain disorders effects different types of neurons which is another reason why we need to be capable of distinguishing them. The neurons that die from Parkinson’s are the neurons that create the chemical dopamine for example.

Another example is balancing the risks for rewards. As Grubb points out “you’d have to have extremely good control over what cells you’re programming, where they’re going to go, and which cells they’ll connect to. If the treatment were to be used to boost grey matter, for example, this could provide a way to improve skills like memory. However, too much grey matter has been linked to causing people to be being easily distracted.

While the research is definitely groundbreaking it is still in its early stages. Hopefully in the near future it will offer treatments to those who need them.

New Scientist