The universe occasionally produces a huge surprise that proves physicists wrong, says Kip Thorne, who grew up in Logan, Utah, with Elder Quentin L. Cook and Merlin Olsen.

For decades, neuroscientists have been trying to pinpoint the neural underpinnings of behavior and decision-making. Past studies suggest that specialized groups of neurons in the mammalian brain, particularly in the cortex, work together to support decision-making and behavioral choices.

Some cortical neurons project to specific regions in the brain. This essentially means that they send axons, projections that transmit electrical impulses from one cell to another, to other areas.

Some neuroscientists have hypothesized that neurons projecting to the same area form specialized “population codes,” coordinated activity patterns that collectively represent specific information.

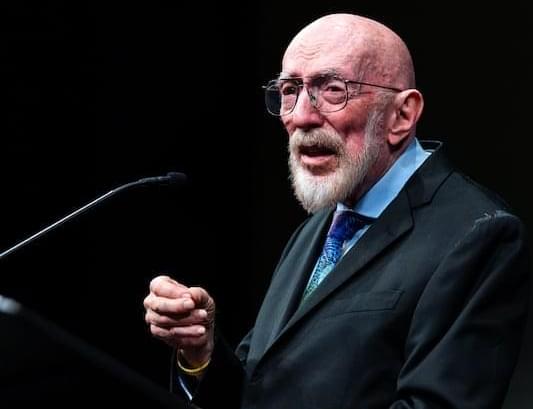

An international research team led by PD Dr. Florian Peissker at the University of Cologne has used the new observation instrument ERIS (Enhanced Resolution Imager and Spectrograph) at the Very Large Telescope (VLT) facility in Chile to show that several so-called “dusty objects” follow stable orbits around the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A at the center of our galaxy.

Earlier studies had surmised that some of these objects could be swallowed up by the black hole. New data refute this assumption. The findings have been published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Researchers have created gyromorphs, a new material that controls light more effectively than any structure used so far in photonic chips.

These hybrid patterns combine order and disorder in a way that stops light from entering from any angle. The discovery solves major limitations found in quasicrystals and other engineered materials. It may open the door to faster, more efficient light-powered computers.

Light-based computers and the need for better materials.

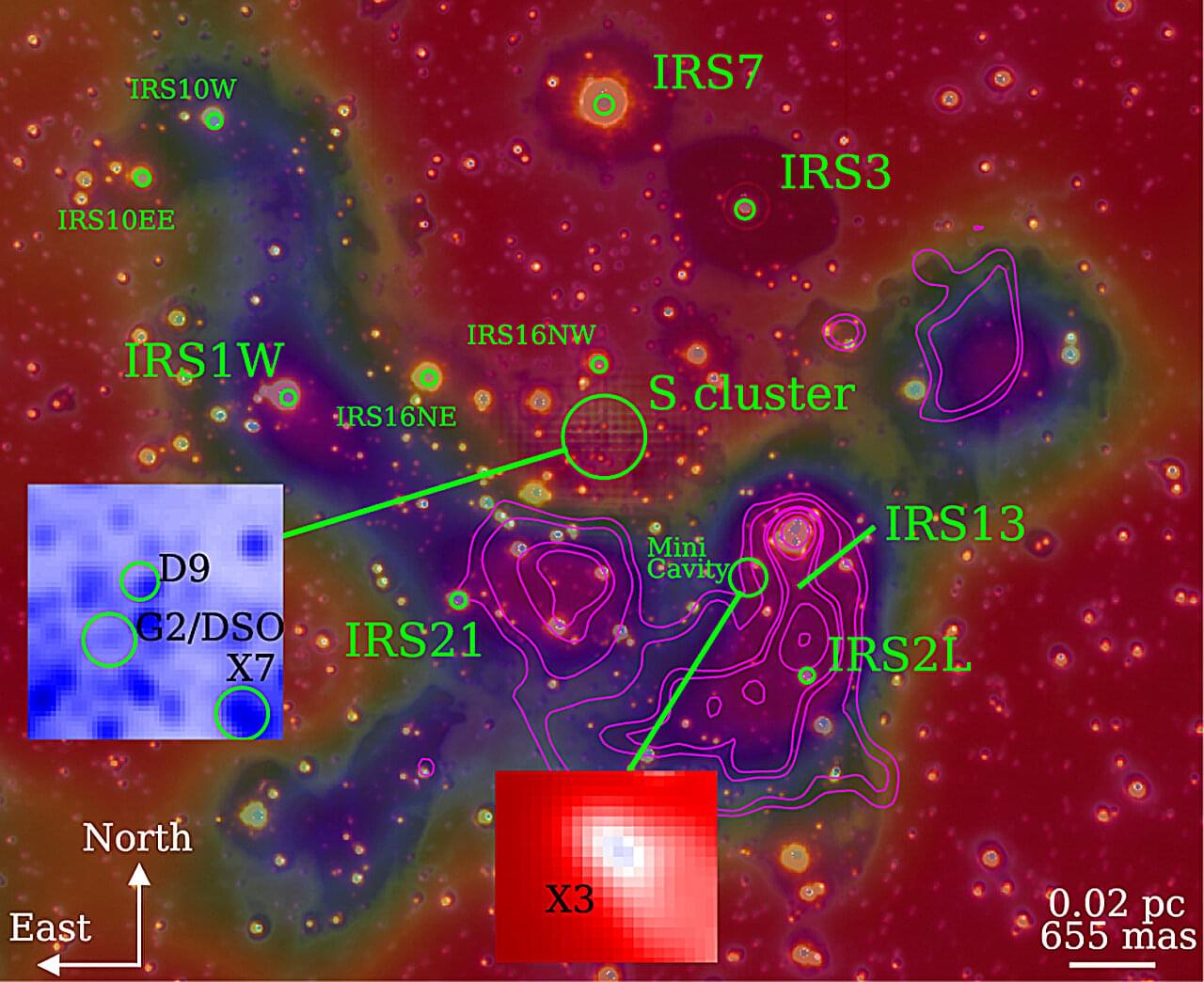

DNA methylation has shown great potential in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) blood diagnosis. However, the ability of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), which can be modified by DNA methylation, to serve as noninvasive biomarkers for AD diagnosis remains unclear.

We performed logistic regression analysis of DNA methylation data from the blood of patients with AD compared and normal controls to identify epigenetically regulated (ER) lncRNAs. Through five machine learning algorithms, we prioritized ER lncRNAs associated with AD diagnosis. An AD blood diagnosis model was constructed based on lncRNA methylation in Australian Imaging, Biomarkers, and Lifestyle (AIBL) subject and verified in two large blood-based studies, the European collaboration for the discovery of novel biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease (AddNeuroMed) and the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). In addition, the potential biological functions and clinical associations of lncRNAs were explored, and their neuropathological roles in AD brain tissue were estimated via cross-tissue analysis.

We characterized the ER lncRNA landscape in AD blood, which is strongly related to AD occurrence and process. Fifteen ER lncRNAs were prioritized to construct an AD blood diagnostic and nomogram model. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the decision and calibration curves show that the model has good prediction performance. We found that the targets and lncRNAs were correlated with AD clinical features. Moreover, cross-tissue analysis revealed that the lncRNA ENSG0000029584 plays both diagnostic and neuropathological roles in AD.

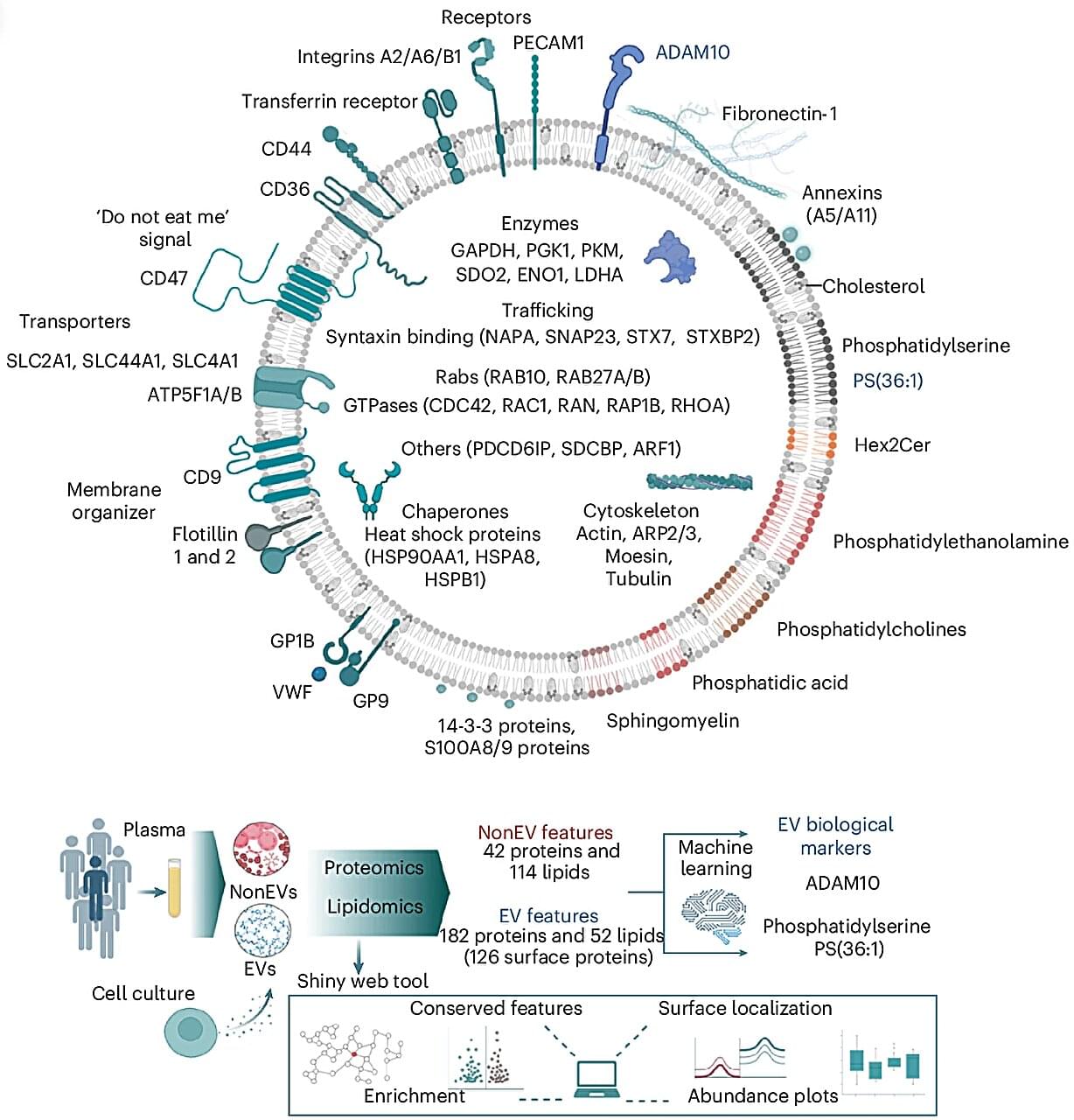

Every second, trillions of tiny parcels travel through your bloodstream—carrying vital information between your body’s cells. Now, scientists at the Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute have opened this molecular mail for the first time, revealing its contents in astonishing detail.

In research published in Nature Cell Biology, Professor David W. Greening and Dr. Alin Rai have mapped the complete molecular blueprint of extracellular vesicles (EVs)—nanosized particles in blood that act as the body’s secret messengers.

For decades, researchers have known that EVs exist, ferrying proteins, fats, and genetic material that mirror the health of their cells of origin. But because blood is a complex mixture—packed with cholesterol, antibodies, and millions of other particles—isolating EVs has long been one of science’s toughest challenges.