Imagine a world with precision medicine, where a swarm of microrobots delivers a payload of medicine directly to ailing cells. Or one where aerial or marine drones can collectively survey an area while exchanging minimal information about their location.

One early step towards realizing such technologies is being able to simultaneously simulate swarming behaviors and synchronized timing—behaviors found in slime molds, sperm and fireflies, for example.

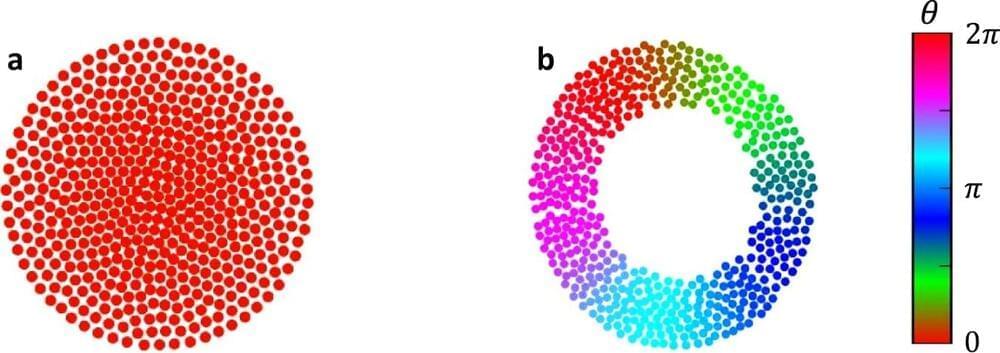

In 2014, Cornell researchers first introduced a simple model of swarmalators—short for “swarming oscillator”—where particles self-organize to synchronize in both time and space. In the study, “Diverse Behaviors in Non-uniform Chiral and Non-chiral Swarmalators,” which published Feb. 20 in the journal Nature Communications, they expanded this model to make it more useful for engineering microrobots; to better understand existing, observed biological behaviors; and for theoreticians to experiment in this field.