Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the top 10 causes of death worldwide. In 2017, 10 million people around the world fell ill with TB and 1.3 million died. The genome of the bacterium that causes TB holds a special toxin-antitoxin system with a surprising function: Once the toxin is activated, all bacterial cells die, stopping the disease. An international research team co-led by the Wilmanns group at EMBL in Hamburg investigated this promising feature for therapeutic targets. They now share the first high-resolution details of the system in Molecular Cell.

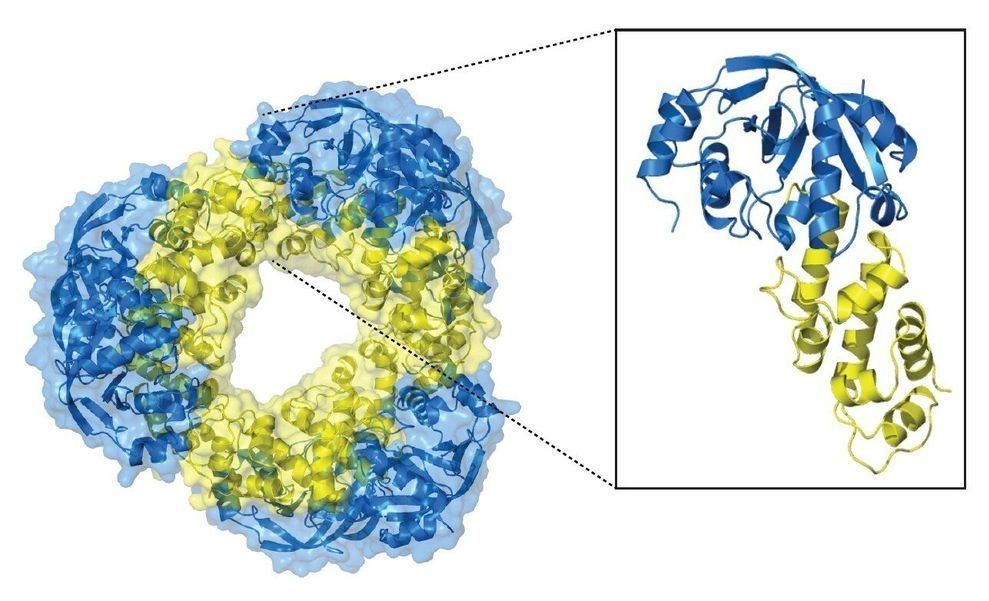

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the bacterium that causes TB in humans. Its genome holds 80 so-called toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems, sets of closely linked genes that encode both a toxic protein and an antitoxin—a toxin-neutralising antidote.

When the bacteria are growing normally, toxin activity is blocked by the antitoxin’s presence. But under stress conditions such as lack of nutrients, dedicated enzymes rapidly degrade the antitoxin molecules. This activates the toxin proteins in the cell and slows down the growth of the bacteria, allowing them to survive the stressful environment.